Alan Jacobs in The Hedgehog Review:

John Betjeman’s life at Oxford was complicated. He wrote poems and made friends, he discovered beauty and rejoiced in it, but he struggled academically, in part because of an impossible relationship with his tutor, who thought him an “idle prig” and did nothing to disguise his hostility. The tutor complained about Betjeman’s silly aestheticism in his diary, but didn’t confine himself to private musings: He treated Betjeman with open contempt, and when Betjeman needed a supportive letter from him, he wrote a rather obviously unsupportive one––which was one reason among several that Betjeman never managed to graduate. What the tutor did not realize was that Betjeman’s frivolous manner was a kind of protective carapace, a way to shield himself from suffering and emotional upheaval.

John Betjeman’s life at Oxford was complicated. He wrote poems and made friends, he discovered beauty and rejoiced in it, but he struggled academically, in part because of an impossible relationship with his tutor, who thought him an “idle prig” and did nothing to disguise his hostility. The tutor complained about Betjeman’s silly aestheticism in his diary, but didn’t confine himself to private musings: He treated Betjeman with open contempt, and when Betjeman needed a supportive letter from him, he wrote a rather obviously unsupportive one––which was one reason among several that Betjeman never managed to graduate. What the tutor did not realize was that Betjeman’s frivolous manner was a kind of protective carapace, a way to shield himself from suffering and emotional upheaval.

The tutor’s name was C.S. Lewis, and before you are too hard on him, please remember that he had just begun teaching, and moreover was not yet a Christian. Later on he and Betjeman had a partial mending of their relationship, but Betjeman never really got over the sting of rejection. He dedicated a book of his poems to Lewis, “whose jolly personality and encouragement to the author in his youth have remained an unfading memory for the author’s declining years.” (Betjeman was 27 at the time.) Later on he wrote a long, anguished, half-apologetic and half-accusatory letter to Lewis, but probably never sent it.

Ultimately they had a lot in common, more and more as years went by and Betjeman drew deeper from the wells of Christian faith and practice. But he never lost the frivolous manner.

More here.

Alexander Polyakov

Alexander Polyakov

Like many public intellectuals who are worth reading,

Like many public intellectuals who are worth reading,  In Akwaeke Emezi’s new book,

In Akwaeke Emezi’s new book,  O

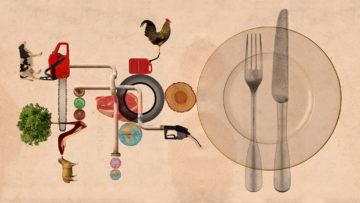

O Marco D’Eramo in The New Left Review’s Sidecar:

Marco D’Eramo in The New Left Review’s Sidecar:

Frankie Thomas in The Paris Review:

Frankie Thomas in The Paris Review: W-3, Bette Howland’s memoir of her stay in a psychiatric hospital following an overdose, was first published in 1974, and comes to us now following the reissue, last year, of her 1978 collection of stories,

W-3, Bette Howland’s memoir of her stay in a psychiatric hospital following an overdose, was first published in 1974, and comes to us now following the reissue, last year, of her 1978 collection of stories,  Is Poe really the most influential American writer? Note that I didn’t say “greatest,” for which there must be at least a dozen viable candidates. But consider his radiant originality. Before his death in 1849 at age 40, Poe largely created the modern short story, while also inventing or perfecting half the genres represented on the bestseller list, including the mystery (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Gold-Bug”), science fiction (“The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion”), psychological suspense (“The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Cask of Amontillado”) and, of course, gothic horror (“The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” the incomparable “Ligeia”).

Is Poe really the most influential American writer? Note that I didn’t say “greatest,” for which there must be at least a dozen viable candidates. But consider his radiant originality. Before his death in 1849 at age 40, Poe largely created the modern short story, while also inventing or perfecting half the genres represented on the bestseller list, including the mystery (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Gold-Bug”), science fiction (“The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” “The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion”), psychological suspense (“The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Cask of Amontillado”) and, of course, gothic horror (“The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” the incomparable “Ligeia”). When I’m stuck—and I’m stuck all the time—I look at “

When I’m stuck—and I’m stuck all the time—I look at “ T

T