George Scialabba at The Baffler:

One of The Free World’s larger themes is the replacement of Paris by New York as “the capital of the modern.” For nearly a century, Menand writes, “Paris was where advanced Western culture—especially painting, sculpture, literature, dance, film, and photography, but also fashion, cuisine, and sexual mores—was . . . created, accredited, and transmitted.” It was not the Nazi occupation that changed things; Paris got off lightly compared with other occupied capitals. (Though it would have been burned to the ground if the German commandant had not ignored Hitler’s orders.) And immediately after the Liberation in 1944, there was a cultural efflorescence. Existentialism was in vogue everywhere; its three main exponents—Sartre, Camus, and Beauvoir—were international celebrities. But the compass needle was turning: as Sartre acknowledged, “the greatest literary development in France between 1929 and 1939 was the discovery of Faulkner, Dos Passos, Hemingway, Caldwell, Steinbeck.” American leadership in painting was even more pronounced in the 1940s and 50s. Paris would always retain its aura, particularly for Black American writers and musicians, though not only for them—Paris would play a large part in liberating Susan Sontag, for example. But American global primacy was so complete in the fifties and sixties that the cultural primacy of its capital city could not be gainsaid.

One of The Free World’s larger themes is the replacement of Paris by New York as “the capital of the modern.” For nearly a century, Menand writes, “Paris was where advanced Western culture—especially painting, sculpture, literature, dance, film, and photography, but also fashion, cuisine, and sexual mores—was . . . created, accredited, and transmitted.” It was not the Nazi occupation that changed things; Paris got off lightly compared with other occupied capitals. (Though it would have been burned to the ground if the German commandant had not ignored Hitler’s orders.) And immediately after the Liberation in 1944, there was a cultural efflorescence. Existentialism was in vogue everywhere; its three main exponents—Sartre, Camus, and Beauvoir—were international celebrities. But the compass needle was turning: as Sartre acknowledged, “the greatest literary development in France between 1929 and 1939 was the discovery of Faulkner, Dos Passos, Hemingway, Caldwell, Steinbeck.” American leadership in painting was even more pronounced in the 1940s and 50s. Paris would always retain its aura, particularly for Black American writers and musicians, though not only for them—Paris would play a large part in liberating Susan Sontag, for example. But American global primacy was so complete in the fifties and sixties that the cultural primacy of its capital city could not be gainsaid.

more here.

Life, for all its complexities, has a simple commonality: It spreads. Plants, animals and bacteria have colonized almost every nook and cranny of our world.

Life, for all its complexities, has a simple commonality: It spreads. Plants, animals and bacteria have colonized almost every nook and cranny of our world.  I celebrated my second pandemic birthday recently. Many things were weird about it: opening presents on Zoom, my phone’s insistent photo reminders from “one year ago today” that could be mistaken for last month, my partner brightly wishing me “iki domuz,” a Turkish phrase that literally means “two pigs.” Well, that last one is actually quite normal in our house. Long ago, I took my first steps into adult language lessons and tried to impress my Turkish American boyfriend on his special day. My younger self nervously bungled through new vocabulary—The numbers! The animals! The months!—to wish him “iki domuz” instead of “happy birthday” (İyi ki doğdun) while we drank like pigs in his tiny apartment outside of UCLA. Now, more than a decade later, that slipup is immortalized as our own peculiar greeting to each other twice a year.

I celebrated my second pandemic birthday recently. Many things were weird about it: opening presents on Zoom, my phone’s insistent photo reminders from “one year ago today” that could be mistaken for last month, my partner brightly wishing me “iki domuz,” a Turkish phrase that literally means “two pigs.” Well, that last one is actually quite normal in our house. Long ago, I took my first steps into adult language lessons and tried to impress my Turkish American boyfriend on his special day. My younger self nervously bungled through new vocabulary—The numbers! The animals! The months!—to wish him “iki domuz” instead of “happy birthday” (İyi ki doğdun) while we drank like pigs in his tiny apartment outside of UCLA. Now, more than a decade later, that slipup is immortalized as our own peculiar greeting to each other twice a year.

Climate change, a pandemic or the coordinated activity of neurons in the brain: In all of these examples, a transition takes place at a certain point from the base state to a new state. Researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have discovered a universal mathematical structure at these so-called tipping points. It creates the basis for a better understanding of the behavior of networked systems.

Climate change, a pandemic or the coordinated activity of neurons in the brain: In all of these examples, a transition takes place at a certain point from the base state to a new state. Researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have discovered a universal mathematical structure at these so-called tipping points. It creates the basis for a better understanding of the behavior of networked systems. Why has the impending eviction of six Palestinian families in East Jerusalem drawn Israelis and Palestinians into a conflict that appears to be spiraling toward yet another war? Because of a word that in the American Jewish community remains largely taboo: the Nakba.

Why has the impending eviction of six Palestinian families in East Jerusalem drawn Israelis and Palestinians into a conflict that appears to be spiraling toward yet another war? Because of a word that in the American Jewish community remains largely taboo: the Nakba. It’s been a long, strange trip in the four decades since Rick Doblin, a pioneering psychedelics researcher, dropped his first hit of acid in college and decided to dedicate his life to the healing powers of mind-altering compounds. Even as antidrug campaigns led to the criminalization of Ecstasy, LSD and magic mushrooms, and drove most researchers from the field, Dr. Doblin continued his quixotic crusade with financial help from his parents. Dr. Doblin’s quest to win mainstream acceptance of psychedelics took a significant leap forward on Monday when the journal

It’s been a long, strange trip in the four decades since Rick Doblin, a pioneering psychedelics researcher, dropped his first hit of acid in college and decided to dedicate his life to the healing powers of mind-altering compounds. Even as antidrug campaigns led to the criminalization of Ecstasy, LSD and magic mushrooms, and drove most researchers from the field, Dr. Doblin continued his quixotic crusade with financial help from his parents. Dr. Doblin’s quest to win mainstream acceptance of psychedelics took a significant leap forward on Monday when the journal  My mother became interested in astrology in the nineteen-eighties. She wasn’t a kook about it; she simply started reading the horoscopes in the Raleigh News & Observer. “Things are going to improve for you financially on the seventeenth,” she’d say over the phone, early in the morning if the prediction was sunny and she thought it might brighten my day. “A good deal of money is coming your way, but with a slight hitch.”

My mother became interested in astrology in the nineteen-eighties. She wasn’t a kook about it; she simply started reading the horoscopes in the Raleigh News & Observer. “Things are going to improve for you financially on the seventeenth,” she’d say over the phone, early in the morning if the prediction was sunny and she thought it might brighten my day. “A good deal of money is coming your way, but with a slight hitch.” “Good architecture can be startling, or at least might not look like what we are used to,” writes the critic Aaron Betsky in Architect magazine. “Experimentation can sometimes look weird at first, but it is a necessary part of figuring out how to make our human-built world better.” Now so used to buildings that break the bounds of convention, we find the suggestion that experimentation is an essential part of good architecture unremarkable, even banal. But is it true?

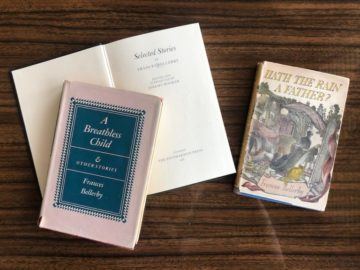

“Good architecture can be startling, or at least might not look like what we are used to,” writes the critic Aaron Betsky in Architect magazine. “Experimentation can sometimes look weird at first, but it is a necessary part of figuring out how to make our human-built world better.” Now so used to buildings that break the bounds of convention, we find the suggestion that experimentation is an essential part of good architecture unremarkable, even banal. But is it true? In Women’s Fiction and the Great War (1997), Nathalie Blondel argues that Bellerby spent the rest of her life replaying this grief in her fiction. “People live double lives” in Bellerby’s stories, Blondel explains: they exist in the land of the living while also “dwelling in memories of the dead.” Like Sabine Coelsch-Foisner—who, in her chapter on women’s writing in the first half of the twentieth-century in The British and Irish Short Story (2008), argues that “Bellerby’s stories typically convey a halt in the continuum of life and verge on the unspeakable”—Blondel highlights how Bellerby demonstrates this linguistically: “the estrangement of the bereaved from the world of the living is imaged through their estrangement from language itself.”

In Women’s Fiction and the Great War (1997), Nathalie Blondel argues that Bellerby spent the rest of her life replaying this grief in her fiction. “People live double lives” in Bellerby’s stories, Blondel explains: they exist in the land of the living while also “dwelling in memories of the dead.” Like Sabine Coelsch-Foisner—who, in her chapter on women’s writing in the first half of the twentieth-century in The British and Irish Short Story (2008), argues that “Bellerby’s stories typically convey a halt in the continuum of life and verge on the unspeakable”—Blondel highlights how Bellerby demonstrates this linguistically: “the estrangement of the bereaved from the world of the living is imaged through their estrangement from language itself.” James Joyce once famously said that if it took him seventeen years to write Finnegans Wake, then a reader should take seventeen years to read it. In his usual prophetic way, he turned out to be exactly right. My Finnegans Wake Reading Group started in July 2004. We finished in February 2021.

James Joyce once famously said that if it took him seventeen years to write Finnegans Wake, then a reader should take seventeen years to read it. In his usual prophetic way, he turned out to be exactly right. My Finnegans Wake Reading Group started in July 2004. We finished in February 2021. At first,

At first,  What if I told you that History is not random? That it follows clear rules?

What if I told you that History is not random? That it follows clear rules?