Hephzibah Anderson in The Guardian:

“Let’s complain”, exhorts Lucy Ellmann in a preface to her first essay collection, Things Are Against Us. And complain she does, though the verb barely seems adequate for the atrabilious, freewheeling fury that spills from its pages. Aimed at everything from air travel to zips, genre writing to men (above all, men), her ire is matched only by an irrepressible comic impulse, from which bubbles forth kitsch puns, wisecracking whimsy and one-liners both bawdy and venomous. As she explains: “In times of pestilence, my fancy turns to shticks.” Goofiness notwithstanding, Ellmann is complaining only to the extent that the sans-culottes grumbled about goings-on at Versailles. She’s out to foment revolution, and this book is nothing less than a manifesto.

“Let’s complain”, exhorts Lucy Ellmann in a preface to her first essay collection, Things Are Against Us. And complain she does, though the verb barely seems adequate for the atrabilious, freewheeling fury that spills from its pages. Aimed at everything from air travel to zips, genre writing to men (above all, men), her ire is matched only by an irrepressible comic impulse, from which bubbles forth kitsch puns, wisecracking whimsy and one-liners both bawdy and venomous. As she explains: “In times of pestilence, my fancy turns to shticks.” Goofiness notwithstanding, Ellmann is complaining only to the extent that the sans-culottes grumbled about goings-on at Versailles. She’s out to foment revolution, and this book is nothing less than a manifesto.

It begins gently enough with the title essay, one of just three not to have already been published elsewhere. Ellmann is tormented by the “conspiratorial manoeuvrings” of inanimate objects. Socks race to get away from her, and pens, credit cards and lemons hurry after them. Paper cuts, soap slips and fitted sheets never do fit. It’s the kind of rogue anthropomorphism at which Dickens, one of her favourite writers, excels, but what really unnerves her is the sense that if these things have it in them to become so hostile, then what potential slights might be delivered by those we’ve really wronged – the vegetables we chow down on, the animals?

Humans are not, in fact, the innocent party here, but the unity of Ellmann’s guilty “we” evaporates in the next essay, Three Strikes, which splits the human race into them and us – them being men, us being women – and more or less keeps it that way until the book’s end. Its message – one that’s rooted in her 2013 novel Mimi, and resounds throughout – is that men have made such a colossal dog’s dinner of running the world, it’s only reasonable for women to take over. She has plenty of ideas for how we’ll rout the patriarchy, including strikes (we must refuse all domestic labour, work and, Lysistrata-style, sex with men) and the compulsory redistribution of male wealth (“yanking cash out of male hands is a humanitarian act”). Matriarchal socialism, she believes, is our sole hope if we’re to save humanity and avert ecological catastrophe.

More here.

In “Visible Republic,” his essay on Dylan winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, Robbins extracts himself from the pro/con squad and tries to isolate the nature of the songwriter (rather than isolate the most literary thing about Dylan because what would that be?). “That’s it, that’s the thing—Dylan isn’t words,” Robbins writes. “He’s words plus [Robbie] Robertson’s uncanny awk, drummer Levon Helm’s cephalopodic clatter, the thin, wild mercury of his voice.” Meaning, one thinks, that by all means win some prizes, who cares, but don’t make one form do another’s work. This exhibits the generosity in both Robbins’s poems and essays. The glittering trash of the world needs itemizing but not sorting. His essay on

In “Visible Republic,” his essay on Dylan winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, Robbins extracts himself from the pro/con squad and tries to isolate the nature of the songwriter (rather than isolate the most literary thing about Dylan because what would that be?). “That’s it, that’s the thing—Dylan isn’t words,” Robbins writes. “He’s words plus [Robbie] Robertson’s uncanny awk, drummer Levon Helm’s cephalopodic clatter, the thin, wild mercury of his voice.” Meaning, one thinks, that by all means win some prizes, who cares, but don’t make one form do another’s work. This exhibits the generosity in both Robbins’s poems and essays. The glittering trash of the world needs itemizing but not sorting. His essay on  Three decades ago, a small group from within the AIDS activist organization ACT UP changed the course of medicine in the United States. They employed what they called “the outside/inside strategy.” The activists staged large, noisy demonstrations outside the Food and Drug Administration and other federal government agencies, demanding an acceleration of the drug-approval process. Others learned the minutiae of the science and worked quietly with receptive bureaucrats, bringing the patient’s perspective to the table toward the same goal of faster drug approval. These were desperate young people dying from a new disease for which there were few treatments and no cure. At first, federal bureaucrats and drug companies resisted, but eventually more AIDS drugs became available.

Three decades ago, a small group from within the AIDS activist organization ACT UP changed the course of medicine in the United States. They employed what they called “the outside/inside strategy.” The activists staged large, noisy demonstrations outside the Food and Drug Administration and other federal government agencies, demanding an acceleration of the drug-approval process. Others learned the minutiae of the science and worked quietly with receptive bureaucrats, bringing the patient’s perspective to the table toward the same goal of faster drug approval. These were desperate young people dying from a new disease for which there were few treatments and no cure. At first, federal bureaucrats and drug companies resisted, but eventually more AIDS drugs became available. Is there any bit of popular philosophical wisdom more useless than the pseudo-Epictetian injunction to “live every day as if it were your last”? If today were my last, I certainly would not have just impulse-ordered an introductory grammar of Lithuanian. Much of what I do each day, in fact, is premised on the expectation that I will continue to do a little bit more of it the day after, and then the day after that, until I accomplish what is intrinsically a massively multi-day project. If I’ve only got one more day to do my stuff, well, the projects I reserve for that special day are hardly going to be the same ones (Lithuanian,

Is there any bit of popular philosophical wisdom more useless than the pseudo-Epictetian injunction to “live every day as if it were your last”? If today were my last, I certainly would not have just impulse-ordered an introductory grammar of Lithuanian. Much of what I do each day, in fact, is premised on the expectation that I will continue to do a little bit more of it the day after, and then the day after that, until I accomplish what is intrinsically a massively multi-day project. If I’ve only got one more day to do my stuff, well, the projects I reserve for that special day are hardly going to be the same ones (Lithuanian,  It’s a nightmare we should have seen coming. In Germany, nuclear power formed around a third of the country’s power generation in 2000, when a Green party-spearheaded campaign managed to secure the gradual closure of plants, citing health and safety concerns. Last year, that share fell to 11%, with all remaining stations scheduled to close by next year. A recent paper found that the last two decades of phased nuclear closures led to an increase in CO2 emissions of

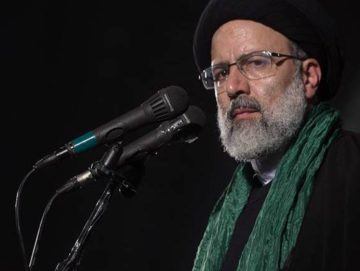

It’s a nightmare we should have seen coming. In Germany, nuclear power formed around a third of the country’s power generation in 2000, when a Green party-spearheaded campaign managed to secure the gradual closure of plants, citing health and safety concerns. Last year, that share fell to 11%, with all remaining stations scheduled to close by next year. A recent paper found that the last two decades of phased nuclear closures led to an increase in CO2 emissions of  Iran’s presidential election on June 18 was the most farcical in the history of the Islamic regime – even more so than the 2009 election, often called an “electoral coup.” It was less an election than a chronicle of a death foretold – the death of what little remained of the constitution’s republican principles. But, in addition to being the most farcical, the election may be the Islamic Republic’s most consequential.

Iran’s presidential election on June 18 was the most farcical in the history of the Islamic regime – even more so than the 2009 election, often called an “electoral coup.” It was less an election than a chronicle of a death foretold – the death of what little remained of the constitution’s republican principles. But, in addition to being the most farcical, the election may be the Islamic Republic’s most consequential. The name of the initiative was Project Cassandra: for the next two years, university researchers would use their expertise to help the German defence ministry predict the future.

The name of the initiative was Project Cassandra: for the next two years, university researchers would use their expertise to help the German defence ministry predict the future. Last October, while waging the government’s new campaign against Islamic forms of “separatism,” French Interior minister Gérald Darmanin complained on television that he was frequently “shocked” to enter a supermarket and see a shelf of “communalist food” (cuisine communautaire).

Last October, while waging the government’s new campaign against Islamic forms of “separatism,” French Interior minister Gérald Darmanin complained on television that he was frequently “shocked” to enter a supermarket and see a shelf of “communalist food” (cuisine communautaire). To live on a day-to-day basis is insufficient for human beings; we need to transcend, transport, escape; we need meaning, understanding, and explanation; we need to see over-all patterns in our lives. We need hope, the sense of a future. And we need freedom (or, at least, the illusion of freedom) to get beyond ourselves, whether with telescopes and microscopes and our ever-burgeoning technology, or in states of mind that allow us to travel to other worlds, to rise above our immediate surroundings. We may seek, too, a relaxing of inhibitions that makes it easier to bond with each other, or transports that make our consciousness of time and mortality easier to bear. We seek a holiday from our inner and outer restrictions, a more intense sense of the here and now, the beauty and value of the world we live in.

To live on a day-to-day basis is insufficient for human beings; we need to transcend, transport, escape; we need meaning, understanding, and explanation; we need to see over-all patterns in our lives. We need hope, the sense of a future. And we need freedom (or, at least, the illusion of freedom) to get beyond ourselves, whether with telescopes and microscopes and our ever-burgeoning technology, or in states of mind that allow us to travel to other worlds, to rise above our immediate surroundings. We may seek, too, a relaxing of inhibitions that makes it easier to bond with each other, or transports that make our consciousness of time and mortality easier to bear. We seek a holiday from our inner and outer restrictions, a more intense sense of the here and now, the beauty and value of the world we live in. Tove Jansson’s writing is different. She has wonderful passages in which entire landscapes are made by peering at blades of grass and scraps of bark. Yet her main Moomin adventures are startlingly catastrophic. For all the light clarity of the prose – which is comic, benign and quizzical – these books show places gripped by ferocious forces, laid waste by storms and floods and snows. They speak (but never obviously) of characters resonating to the winds and seas around them. They include visions that now read like warnings of climate change: “the great gap that had been the sea in front of them, the dark red sky overhead, and behind, the forest panting in the heat”.

Tove Jansson’s writing is different. She has wonderful passages in which entire landscapes are made by peering at blades of grass and scraps of bark. Yet her main Moomin adventures are startlingly catastrophic. For all the light clarity of the prose – which is comic, benign and quizzical – these books show places gripped by ferocious forces, laid waste by storms and floods and snows. They speak (but never obviously) of characters resonating to the winds and seas around them. They include visions that now read like warnings of climate change: “the great gap that had been the sea in front of them, the dark red sky overhead, and behind, the forest panting in the heat”. Almost 75 years ago John Gunther produced his amazing profile of our country, “Inside U.S.A.” — more than 900 pages long, and still riveting from start to finish. It started out with a first printing of 125,000 copies — the largest first printing in the history of Harper & Brothers — plus 380,000 more for the Book-of-the-Month Club. It was the third-biggest nonfiction best seller of 1947 (ahead of it, only Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman’s “Peace of Mind” and the “Information Please Almanac”). It was a phenomenon, but not a surprise: Gunther’s first great success, “Inside Europe,” published in 1936, had helped alert the world to the realities of fascism and Stalinism; “Inside Asia” and “Inside Latin America” followed, with comparable success — all three of these books were among the top sellers of their year, as would be “Inside Africa” and “Inside Russia Today,” yet to come. His “Roosevelt in Retrospect” (1950) is one of the best political biographies I’ve ever come across, a mere 400 pages long and pure pleasure to read. Like “Inside U.S.A.,” it is out of print — please, American publishers, one of you make them reappear.

Almost 75 years ago John Gunther produced his amazing profile of our country, “Inside U.S.A.” — more than 900 pages long, and still riveting from start to finish. It started out with a first printing of 125,000 copies — the largest first printing in the history of Harper & Brothers — plus 380,000 more for the Book-of-the-Month Club. It was the third-biggest nonfiction best seller of 1947 (ahead of it, only Rabbi Joshua Loth Liebman’s “Peace of Mind” and the “Information Please Almanac”). It was a phenomenon, but not a surprise: Gunther’s first great success, “Inside Europe,” published in 1936, had helped alert the world to the realities of fascism and Stalinism; “Inside Asia” and “Inside Latin America” followed, with comparable success — all three of these books were among the top sellers of their year, as would be “Inside Africa” and “Inside Russia Today,” yet to come. His “Roosevelt in Retrospect” (1950) is one of the best political biographies I’ve ever come across, a mere 400 pages long and pure pleasure to read. Like “Inside U.S.A.,” it is out of print — please, American publishers, one of you make them reappear. Wolfgang Streeck in the New Left Review‘s Sidecar:

Wolfgang Streeck in the New Left Review‘s Sidecar: Matthieu Queloz in Aeon:

Matthieu Queloz in Aeon: