Lorna Finlayson in Sidecar:

Lorna Finlayson in Sidecar:

Philosophy in the so-called ‘analytic’ tradition has a strange relationship with politics. Normally seen as originating with Frege, Moore, Russell and Wittgenstein in the early 20th century, analytic philosophy was originally concerned with using formal logic to clarify and resolve fundamental metaphysical questions. Politics was largely ignored, according to the Oxford analyst Anthony Quinton, before the late 1960s. Political philosophy, in fact, was routinely pronounced ‘dead’ at the hands of the analysts – so dead that the tepid output of John Rawls (whose A Theory of Justice was published in 1971) could appear as a revival.

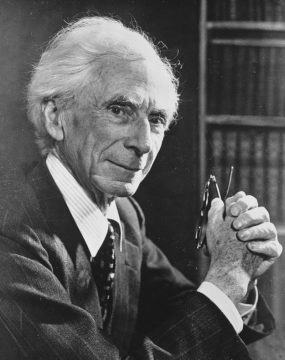

At the same time, analytic philosophers were not uninterested in politics. Bertrand Russell is an especially well-known case, but other figures such as A. J. Ayer and Stuart Hampshire – both supporters of the Labour Party (and in Ayer’s case, later the Social Democratic Party) and critics of the Vietnam War – were also politically involved. The reluctance to engage with politics in their professional capacities might seem thus to reflect not lack of political interest, but a view of philosophy as a largely separate sphere. Russell, for example, wrote that his ‘technical activities must be forgotten’ in order for his popular political writings to be properly understood, while Hampshire argued that although analytic philosophers ‘might happen to have political interests, […] their philosophical arguments were largely neutral politically.’

While at times insistent on the detachment of their philosophy from politics – stretching to a pride in the ‘conspicuous triviality’ of their own activity that the critic of ‘ordinary language philosophy’ Ernest Gellner saw as requiring the explanation of social historians – the analysts at other times floated some quite strong claims as to the political value and potential of their own ways of doing things.

More here.

Macabe Keliher in Boston Review:

Macabe Keliher in Boston Review: Ho-fung Hung in Phenomenal World:

Ho-fung Hung in Phenomenal World: DENIS JOHNSON UNDERSTOOD the impulse to check out. He understood a lot of things, including the contradictory nature of truth. He himself was the son of a US State Department employee stationed overseas, a well-to-do suburban American boy who was “saved” from the penitentiary, as he put it, by “the Beatnik category.” He went to college, published a book of poetry by the age of nineteen (The Man Among the Seals), went to graduate school and got an MFA, but was also an alkie drifter and heroin addict: a “real” writer, in other words (who, like any really real writer, can’t be pigeonholed by one coherent myth, or by trite ideas about the school of life). Later he got clean and became some kind of Christian, published many novels and a book of outstanding essays (Seek), lived in remote northern Idaho but traveled and wrote into multiple zones of conflict—Somalia, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan, and famously, in Tree of Smoke, wartime Vietnam. Perhaps being raised abroad, in various far-flung locations (Germany, the Philippines, and Japan), gave him a better feeling for the lost and ugly American, the juncture of the epic and pathetic, the suicidal tendencies of the everyday joe, which seem to have been his wellspring.

DENIS JOHNSON UNDERSTOOD the impulse to check out. He understood a lot of things, including the contradictory nature of truth. He himself was the son of a US State Department employee stationed overseas, a well-to-do suburban American boy who was “saved” from the penitentiary, as he put it, by “the Beatnik category.” He went to college, published a book of poetry by the age of nineteen (The Man Among the Seals), went to graduate school and got an MFA, but was also an alkie drifter and heroin addict: a “real” writer, in other words (who, like any really real writer, can’t be pigeonholed by one coherent myth, or by trite ideas about the school of life). Later he got clean and became some kind of Christian, published many novels and a book of outstanding essays (Seek), lived in remote northern Idaho but traveled and wrote into multiple zones of conflict—Somalia, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan, and famously, in Tree of Smoke, wartime Vietnam. Perhaps being raised abroad, in various far-flung locations (Germany, the Philippines, and Japan), gave him a better feeling for the lost and ugly American, the juncture of the epic and pathetic, the suicidal tendencies of the everyday joe, which seem to have been his wellspring. In 1913 and 1914, Mexico suffered under a cruel dictator, Victoriano Huerta, who had gained power by assassinating that nation’s democratically elected president in a U.S.-sanctioned coup. Hoping to restore representative government, four unlikely allies joined forces to defeat Huerta. They called themselves Constitutionalists. The consequences of the Constitutionalists’ victory for both Mexico and the United States are the focus of Texas historian Jeff Guinn’s “

In 1913 and 1914, Mexico suffered under a cruel dictator, Victoriano Huerta, who had gained power by assassinating that nation’s democratically elected president in a U.S.-sanctioned coup. Hoping to restore representative government, four unlikely allies joined forces to defeat Huerta. They called themselves Constitutionalists. The consequences of the Constitutionalists’ victory for both Mexico and the United States are the focus of Texas historian Jeff Guinn’s “ Sitting in an isolated room at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Frank Nielsen steeled himself for the first injection. Doctors were about to take a needle filled with herpes simplex virus, the strain responsible for cold sores, and plunge it directly into his scalp. If all went well, it would likely save his life.

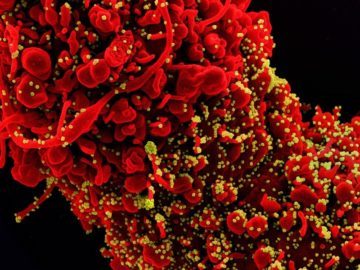

Sitting in an isolated room at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Frank Nielsen steeled himself for the first injection. Doctors were about to take a needle filled with herpes simplex virus, the strain responsible for cold sores, and plunge it directly into his scalp. If all went well, it would likely save his life.

The first time I saw the Breonna Taylor memorial was on a livestream. It was summer of 2020, and I watched a small team of people at Injustice Square shake out tarps and cover the collection of paintings and signs to protect them from rain. The second time I saw it was in person. I walked around it, noticed the nameplates inscribed with the names of the other Black men and women killed by police encircling its edges. There was one painting of Taylor that was massive, vibrant; a sheen of purple glistened in her hair, and a small jewel glittered in her nose. At its base were poster boards proclaiming “Justice for Bre” and “She was asleep.” Around me, protestors shouted out some of those same lines through their masks.

The first time I saw the Breonna Taylor memorial was on a livestream. It was summer of 2020, and I watched a small team of people at Injustice Square shake out tarps and cover the collection of paintings and signs to protect them from rain. The second time I saw it was in person. I walked around it, noticed the nameplates inscribed with the names of the other Black men and women killed by police encircling its edges. There was one painting of Taylor that was massive, vibrant; a sheen of purple glistened in her hair, and a small jewel glittered in her nose. At its base were poster boards proclaiming “Justice for Bre” and “She was asleep.” Around me, protestors shouted out some of those same lines through their masks. Researchers developing the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine have identified biomarkers that can help to predict whether someone will be protected by the jab they receive. The team at the University of Oxford, UK, identified a ‘correlate of protection’ from the immune responses of trial participants — the first found by any COVID-19 vaccine developer. Identifying such blood markers, scientists say, will improve existing vaccines and speed the development of new ones by reducing the need for costly large-scale efficacy trials.

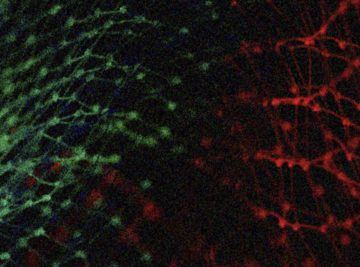

Researchers developing the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine have identified biomarkers that can help to predict whether someone will be protected by the jab they receive. The team at the University of Oxford, UK, identified a ‘correlate of protection’ from the immune responses of trial participants — the first found by any COVID-19 vaccine developer. Identifying such blood markers, scientists say, will improve existing vaccines and speed the development of new ones by reducing the need for costly large-scale efficacy trials. “Neuroaesthetics can perhaps be understood in the Duchampian sense,” he claimed in a 2004 interview. “Neuroscience is a readymade, which is recontextualized out from its original context as a scientific-based paradigm into one that is aesthetically based.” He pointed to Conceptualists like Dan Graham and Sol LeWitt as precursors of a later generation of artists who would act as mediators between an increasingly technologized and monetized society and its hyperactive visual culture. Neuroaesthetics endeavored not to produce a synthesis of neuroscience and aesthetics, but rather to estrange the former from normal usage—much as Duchamp did the bicycle wheel and bottle rack—and reenvision in a more psychodynamic capacity its tools for mapping cognitive categories such as color, memory, and spatial relationships, in order to reveal, in Neidich’s words, “the idea of becoming brain.”

“Neuroaesthetics can perhaps be understood in the Duchampian sense,” he claimed in a 2004 interview. “Neuroscience is a readymade, which is recontextualized out from its original context as a scientific-based paradigm into one that is aesthetically based.” He pointed to Conceptualists like Dan Graham and Sol LeWitt as precursors of a later generation of artists who would act as mediators between an increasingly technologized and monetized society and its hyperactive visual culture. Neuroaesthetics endeavored not to produce a synthesis of neuroscience and aesthetics, but rather to estrange the former from normal usage—much as Duchamp did the bicycle wheel and bottle rack—and reenvision in a more psychodynamic capacity its tools for mapping cognitive categories such as color, memory, and spatial relationships, in order to reveal, in Neidich’s words, “the idea of becoming brain.” Bridges connect us – and they have since the beginning of time, all the way back to the very first bridge, the rainbow. They connect us geographically, strategically, metaphorically, lyrically (if that last seems a stretch, think of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Waters”). Now we have a book to explain all sorts of bridges to us, thanks to UCLA author

Bridges connect us – and they have since the beginning of time, all the way back to the very first bridge, the rainbow. They connect us geographically, strategically, metaphorically, lyrically (if that last seems a stretch, think of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Waters”). Now we have a book to explain all sorts of bridges to us, thanks to UCLA author  “What is the use of stories that aren’t even true?” Haroun asks his father in Salman Rushdie’s delightful and inexplicably underrated crossover novel. Rushdie suggests the issue it raises, the relationship between the “world of imagination and the so-called real world”, has occupied most of his writing life.

“What is the use of stories that aren’t even true?” Haroun asks his father in Salman Rushdie’s delightful and inexplicably underrated crossover novel. Rushdie suggests the issue it raises, the relationship between the “world of imagination and the so-called real world”, has occupied most of his writing life. The Universal Approximation Theorem is, very literally, the theoretical foundation of why neural networks work. Put simply, it states that a neural network with one hidden layer containing a sufficient but finite number of neurons can approximate any continuous function to a reasonable accuracy, under certain conditions for activation functions (namely, that they must be sigmoid-like).

The Universal Approximation Theorem is, very literally, the theoretical foundation of why neural networks work. Put simply, it states that a neural network with one hidden layer containing a sufficient but finite number of neurons can approximate any continuous function to a reasonable accuracy, under certain conditions for activation functions (namely, that they must be sigmoid-like).