Andrew Sullivan in The Weekly Dish:

As the origins of our current moral panic about “white supremacy” become more widely debated, we have an obvious problem: how to define the term “Critical Race Theory.” This was never going to be easy, since so much of the academic discourse behind the term is deliberately impenetrable, as it tries to disrupt and dismantle the Western concept of discourse itself. The sheer volume of jargon words, and their mutual relationships, along with the usual internal bitter controversies, all serve to sow confusion.

As the origins of our current moral panic about “white supremacy” become more widely debated, we have an obvious problem: how to define the term “Critical Race Theory.” This was never going to be easy, since so much of the academic discourse behind the term is deliberately impenetrable, as it tries to disrupt and dismantle the Western concept of discourse itself. The sheer volume of jargon words, and their mutual relationships, along with the usual internal bitter controversies, all serve to sow confusion.

This conceptual muddle also allows everyone to have their own definition and gives critical theorists the opportunity to denounce anyone from the outside trying to explain it. So it may be helpful to home in on what I think is a core point. No, I’m not a trained critical theorist. But no one should have to be in order to engage a field of thought with such vast public ramifications. But I have spent many years studying political theory, which is why, perhaps, I am so concerned. And, for me, the argument is not really about race, or gender, or history, or identity as such.

More here. And a primer on Critical Race Theory from The Factual here.

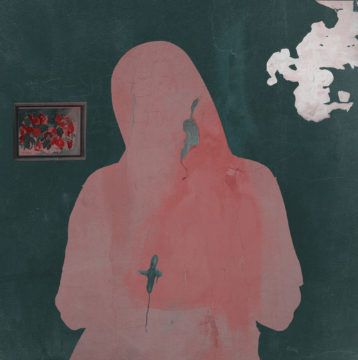

In many of our contemporary cultures, the realities of death feel unapproachable. Traditional grieving methods are routinely relegated to the margins, replaced by the medical promise of comforting objectivity. But for those of us confronted by the ebb and flow of complex emotions in the wake of death, the assurance of objectivity falls short. For Ioanna Sakellaraki, this evolving emotional storm, experienced head-on in the wake of her father’s death, is what prompted her to pursue a project on bereavement, finding ways to document the organic chaos that she describes as “the passageway into a liminal space of absence and presence.”

In many of our contemporary cultures, the realities of death feel unapproachable. Traditional grieving methods are routinely relegated to the margins, replaced by the medical promise of comforting objectivity. But for those of us confronted by the ebb and flow of complex emotions in the wake of death, the assurance of objectivity falls short. For Ioanna Sakellaraki, this evolving emotional storm, experienced head-on in the wake of her father’s death, is what prompted her to pursue a project on bereavement, finding ways to document the organic chaos that she describes as “the passageway into a liminal space of absence and presence.” W

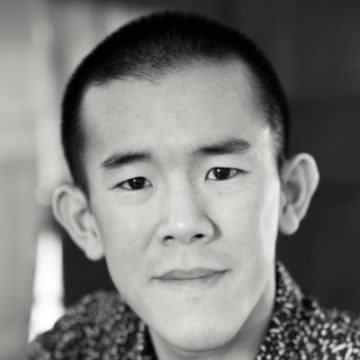

W The Atlantic staff writer Ed Yong has won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. He was awarded journalism’s top honor for his defining coverage of the coronavirus pandemic and how America failed in its response to the virus. This is The Atlantic’s first Pulitzer Prize.

The Atlantic staff writer Ed Yong has won the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting. He was awarded journalism’s top honor for his defining coverage of the coronavirus pandemic and how America failed in its response to the virus. This is The Atlantic’s first Pulitzer Prize. When challenged, former President Donald Trump often claimed he was the victim of

When challenged, former President Donald Trump often claimed he was the victim of  Nero, who was enthroned in Rome in 54 A.D., at the age of sixteen, and went on to rule for nearly a decade and a half, developed a reputation for tyranny, murderous cruelty, and decadence that has survived for nearly two thousand years. According to various Roman historians, he commissioned the assassination of Agrippina the Younger—his mother and sometime lover. He sought to poison her, then to have her crushed by a falling ceiling or drowned in a self-sinking boat, before ultimately having her murder disguised as a suicide. Nero was betrothed at eleven and married at fifteen, to his adoptive stepsister, Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the emperor Claudius. At the age of twenty-four, Nero divorced her, banished her, ordered her bound with her wrists slit, and had her suffocated in a steam bath. He received her decapitated head when it was delivered to his court. He also murdered his second wife, the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her in the belly while she was pregnant.

Nero, who was enthroned in Rome in 54 A.D., at the age of sixteen, and went on to rule for nearly a decade and a half, developed a reputation for tyranny, murderous cruelty, and decadence that has survived for nearly two thousand years. According to various Roman historians, he commissioned the assassination of Agrippina the Younger—his mother and sometime lover. He sought to poison her, then to have her crushed by a falling ceiling or drowned in a self-sinking boat, before ultimately having her murder disguised as a suicide. Nero was betrothed at eleven and married at fifteen, to his adoptive stepsister, Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the emperor Claudius. At the age of twenty-four, Nero divorced her, banished her, ordered her bound with her wrists slit, and had her suffocated in a steam bath. He received her decapitated head when it was delivered to his court. He also murdered his second wife, the noblewoman Poppaea Sabina, by kicking her in the belly while she was pregnant. To become prime minister, Mr. Modi overcame a reputation tarnished by his alleged involvement in

To become prime minister, Mr. Modi overcame a reputation tarnished by his alleged involvement in  Mona Ali in Phenomenal World:

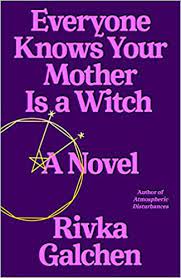

Mona Ali in Phenomenal World: Leo Robson in the NLR’s Sidecar:

Leo Robson in the NLR’s Sidecar: Steven Pinker: The idea behind effective altruism is to channel charitable giving and other philanthropic activities to where they will do the most good, where they would lead to the greatest increase in human flourishing. And the reason that it’s needed is that we are all altruistic. It is part of human nature. On the other hand, we have a large set of motives for why we’re altruistic and some of them are ulterior — such as appearing beneficent and generous, or earning friends and cooperation partners. Some of them may result in conspicuous sacrifices that indicate that we are generous and trustworthy people to our peers but don’t necessarily do anyone any good. And so the idea behind effective altruism is to determine where your activities actually save lives, increase health, reduce poverty, and at the very least provide people opportunities to channel their philanthropy where it will do the most good. And, of course, also to encourage people to do that. So part of it is just informing people if that is their goal and telling them that these are the ways to do it. And the other is to spread the value that that’s where philanthropy ought to be directed.

Steven Pinker: The idea behind effective altruism is to channel charitable giving and other philanthropic activities to where they will do the most good, where they would lead to the greatest increase in human flourishing. And the reason that it’s needed is that we are all altruistic. It is part of human nature. On the other hand, we have a large set of motives for why we’re altruistic and some of them are ulterior — such as appearing beneficent and generous, or earning friends and cooperation partners. Some of them may result in conspicuous sacrifices that indicate that we are generous and trustworthy people to our peers but don’t necessarily do anyone any good. And so the idea behind effective altruism is to determine where your activities actually save lives, increase health, reduce poverty, and at the very least provide people opportunities to channel their philanthropy where it will do the most good. And, of course, also to encourage people to do that. So part of it is just informing people if that is their goal and telling them that these are the ways to do it. And the other is to spread the value that that’s where philanthropy ought to be directed. ROSENBAUM:

ROSENBAUM:  In the early 90s, governments started buying into an argument about capital mobility, taxes and welfare states: in a world of global capital, investors will seek the best returns they can get globally. If those returns are reduced by “distortions” such as taxes, investment will flow to countries that tax less. Consequently, those expensive and expansive welfare states that neoliberal economists had always targeted had to go. Funding them through taxing the wealthy and corporations would lower investment and employment, so the story went.

In the early 90s, governments started buying into an argument about capital mobility, taxes and welfare states: in a world of global capital, investors will seek the best returns they can get globally. If those returns are reduced by “distortions” such as taxes, investment will flow to countries that tax less. Consequently, those expensive and expansive welfare states that neoliberal economists had always targeted had to go. Funding them through taxing the wealthy and corporations would lower investment and employment, so the story went.