Morgan Meis in The New Yorker:

In 2013, a philosopher and ecologist named Timothy Morton proposed that humanity had entered a new phase. What had changed was our relationship to the nonhuman. For the first time, Morton wrote, we had become aware that “nonhuman beings” were “responsible for the next moment of human history and thinking.” The nonhuman beings Morton had in mind weren’t computers or space aliens but a particular group of objects that were “massively distributed in time and space.” Morton called them “hyperobjects”: all the nuclear material on earth, for example, or all the plastic in the sea. “Everyone must reckon with the power of rising waves and ultraviolet light,” Morton wrote, in “Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World.” Those rising waves were being created by a hyperobject: all the carbon in the atmosphere.

In 2013, a philosopher and ecologist named Timothy Morton proposed that humanity had entered a new phase. What had changed was our relationship to the nonhuman. For the first time, Morton wrote, we had become aware that “nonhuman beings” were “responsible for the next moment of human history and thinking.” The nonhuman beings Morton had in mind weren’t computers or space aliens but a particular group of objects that were “massively distributed in time and space.” Morton called them “hyperobjects”: all the nuclear material on earth, for example, or all the plastic in the sea. “Everyone must reckon with the power of rising waves and ultraviolet light,” Morton wrote, in “Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World.” Those rising waves were being created by a hyperobject: all the carbon in the atmosphere.

Hyperobjects are real, they exist in our world, but they are also beyond us. We know a piece of Styrofoam when we see it—it’s white, spongy, light as air—and yet fourteen million tons of Styrofoam are produced every year; chunks of it break down into particles that enter other objects, including animals. Although Styrofoam is everywhere, one can never point to all the Styrofoam in the world and say, “There it is.” Ultimately, Morton writes, whatever bit of Styrofoam you may be interacting with at any particular moment is only a “local manifestation” of a larger whole that exists in other places and will exist on this planet millennia after you are dead.

More here.

Gilles Demaneuf is a data scientist with the Bank of New Zealand in Auckland. He was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome ten years ago, and believes it gives him a professional advantage. “I’m very good at finding patterns in data, when other people see nothing,” he says.

Gilles Demaneuf is a data scientist with the Bank of New Zealand in Auckland. He was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome ten years ago, and believes it gives him a professional advantage. “I’m very good at finding patterns in data, when other people see nothing,” he says. Thirty years have passed since journalists were cut off from Punjab, and Punjab from the world. In June of each year, Sikhs throng to gurudwaras to observe one of the most significant of their religious holidays. On this day, when even the less observant find their way to gurudwaras, the Indian Army attacked Darbar Sahib—the Golden Temple, the Sikh Vatican —and dozens of other gurudwaras across the state.

Thirty years have passed since journalists were cut off from Punjab, and Punjab from the world. In June of each year, Sikhs throng to gurudwaras to observe one of the most significant of their religious holidays. On this day, when even the less observant find their way to gurudwaras, the Indian Army attacked Darbar Sahib—the Golden Temple, the Sikh Vatican —and dozens of other gurudwaras across the state. Nations, like individuals

Nations, like individuals In a recent study

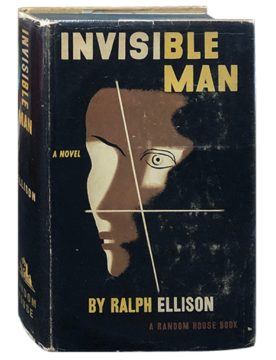

In a recent study In a speech to the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers in Moscow in 1934, Central Committee secretary Andreï Zhdanov reminded those assembled of Comrade Stalin’s recent declaration that, in the Soviet Union, writers are now “the engineers of the human soul”.

In a speech to the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers in Moscow in 1934, Central Committee secretary Andreï Zhdanov reminded those assembled of Comrade Stalin’s recent declaration that, in the Soviet Union, writers are now “the engineers of the human soul”. In the 1950s, four decades before he won a Nobel Prize for his contributions to

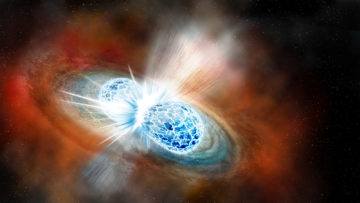

In the 1950s, four decades before he won a Nobel Prize for his contributions to  On June 2 ,Bill Gates’ advanced nuclear reactor company TerraPower, and Warren Buffett’s PacifiCorp announced that they’ve chosen Wyoming as the state to launch their Natrium advanced nuclear reactor project.

On June 2 ,Bill Gates’ advanced nuclear reactor company TerraPower, and Warren Buffett’s PacifiCorp announced that they’ve chosen Wyoming as the state to launch their Natrium advanced nuclear reactor project. Five years ago this month, I attended the

Five years ago this month, I attended the  I first saw

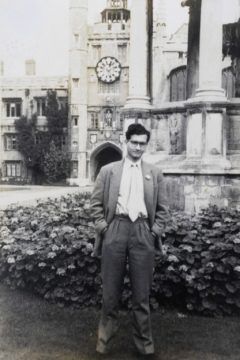

I first saw  Coming from a long line of Hindu intellectuals and teachers, Amartya Sen enjoyed advantages and freedoms that few others did in a deeply-stratified India of the 1930s, during the waning days of the British empire. Teaching was in his blood, and from an early age, Sen was struck by the stark economic inequities he saw all around him under the British raj. Identifying and understanding the causes and effects that inequalities, like those surrounding poverty or gender, had on people’s lives would become a lifelong intellectual lodestar for the political economist, moral philosopher, and social theorist. Many economists focus on explaining and predicting what is happening in the world. But Sen, considered the key figure at the convergence of economics and philosophy, turned his attention instead to what the reality should be and why we fall short. “I think he’s the greatest living figure in normative economics, which asks not ‘What do we see?’ but ‘What should we aspire to?’ and ‘How do we even work out what we should aspire to?’” said Eric S. Maskin ’72, Ph.D. ’76, Adams University Professor and professor of economics and mathematics.

Coming from a long line of Hindu intellectuals and teachers, Amartya Sen enjoyed advantages and freedoms that few others did in a deeply-stratified India of the 1930s, during the waning days of the British empire. Teaching was in his blood, and from an early age, Sen was struck by the stark economic inequities he saw all around him under the British raj. Identifying and understanding the causes and effects that inequalities, like those surrounding poverty or gender, had on people’s lives would become a lifelong intellectual lodestar for the political economist, moral philosopher, and social theorist. Many economists focus on explaining and predicting what is happening in the world. But Sen, considered the key figure at the convergence of economics and philosophy, turned his attention instead to what the reality should be and why we fall short. “I think he’s the greatest living figure in normative economics, which asks not ‘What do we see?’ but ‘What should we aspire to?’ and ‘How do we even work out what we should aspire to?’” said Eric S. Maskin ’72, Ph.D. ’76, Adams University Professor and professor of economics and mathematics.

Ben Bakkum in Macro Chronicles:

Ben Bakkum in Macro Chronicles: