Category: Recommended Reading

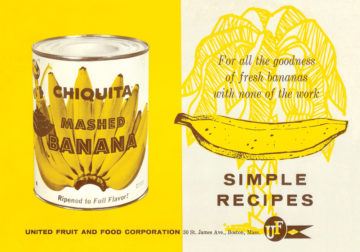

The Colonial Adventures Of The United Fruit Company

Larry Tye at Cabinet Magazine:

The United Fruit Company was born over a bottle of rum. In 1870, Lorenzo Dow Baker, skipper of the Boston schooner Telegraph, pulled into Jamaica for a taste of the island’s famous distilled alcohol and a load of bamboo. While he was drinking, a local tradesman came by offering green bananas; Baker bought 160 bunches at twenty-five cents each. He resold them in New York for up to $3.25 a bunch, a deal so sweet he couldn’t resist doing it again. By 1885, eleven ships were flying under the banner of the new Boston Fruit Company, bringing to the United States ten million bunches of bananas a year. United Fruit was formed in 1899, with assets that included more than 210,000 acres of land across the Caribbean and Central America and enough political clout that Honduras, Costa Rica, and other countries in the region became known as “banana republics.”

The United Fruit Company was born over a bottle of rum. In 1870, Lorenzo Dow Baker, skipper of the Boston schooner Telegraph, pulled into Jamaica for a taste of the island’s famous distilled alcohol and a load of bamboo. While he was drinking, a local tradesman came by offering green bananas; Baker bought 160 bunches at twenty-five cents each. He resold them in New York for up to $3.25 a bunch, a deal so sweet he couldn’t resist doing it again. By 1885, eleven ships were flying under the banner of the new Boston Fruit Company, bringing to the United States ten million bunches of bananas a year. United Fruit was formed in 1899, with assets that included more than 210,000 acres of land across the Caribbean and Central America and enough political clout that Honduras, Costa Rica, and other countries in the region became known as “banana republics.”

The company also soon had a kingpin worthy of its swashbuckling history: Samuel Zemurray, better known as Sam the Banana Man.

more here.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction

Tanya Harrod at Literary Review:

This year, Tate is hosting four exhibitions devoted to women artists: Paula Rego, Lubaina Himid, Yayoi Kusama and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (a further show devoted to Magdalena Abakanowicz is in the pipeline). Opening on 15 July at Tate Modern, the exhibition ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction’ comes with an excellent catalogue, which includes sixteen essays that survey her remarkable range. This Swiss artist, born in Davos in 1889, created textiles, beadwork bags and necklaces, cross-stitch embroidery, carnivalesque outfits for costume balls and a family of haunting marionettes, as well as designing furniture and interiors. She was also a Laban-trained dancer, a sculptor, an illustrator, co-editor of the important journal Plastique, a brilliant photographer and a significant abstract artist. And as if that were not enough, she gave continuous support to her husband, Jean Arp, and designed the modern vernacular house at Clamart in the southwestern suburbs of Paris where she and Arp lived from 1928 until being driven south by the German invasion in 1940. Her husband, whom she married in 1922, is regularly name-checked in surveys of 20th-century art, from Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting to Norbert Lynton’s The Story of Modern Art. By contrast, Taeuber-Arp’s reputation was only properly recuperated in 2005 in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois and Benjamin Buchloh’s generous Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism.

This year, Tate is hosting four exhibitions devoted to women artists: Paula Rego, Lubaina Himid, Yayoi Kusama and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (a further show devoted to Magdalena Abakanowicz is in the pipeline). Opening on 15 July at Tate Modern, the exhibition ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction’ comes with an excellent catalogue, which includes sixteen essays that survey her remarkable range. This Swiss artist, born in Davos in 1889, created textiles, beadwork bags and necklaces, cross-stitch embroidery, carnivalesque outfits for costume balls and a family of haunting marionettes, as well as designing furniture and interiors. She was also a Laban-trained dancer, a sculptor, an illustrator, co-editor of the important journal Plastique, a brilliant photographer and a significant abstract artist. And as if that were not enough, she gave continuous support to her husband, Jean Arp, and designed the modern vernacular house at Clamart in the southwestern suburbs of Paris where she and Arp lived from 1928 until being driven south by the German invasion in 1940. Her husband, whom she married in 1922, is regularly name-checked in surveys of 20th-century art, from Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting to Norbert Lynton’s The Story of Modern Art. By contrast, Taeuber-Arp’s reputation was only properly recuperated in 2005 in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois and Benjamin Buchloh’s generous Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism.

more here.

The Remarkable Effectiveness of Pete Buttigieg on Fox News

Benjamin Wallace-Wells in The New Yorker:

Television suits Peter Buttigieg. He is a dispassionate figure in an emotional medium. In response to ridiculousness, his face stays largely still, but his peaked eyebrows rise a notch. As a politician, Buttigieg’s great trick (it’s also a flaw) is to never take anything personally: he blinks away the noisy, slanderous business of daily politics in pursuit of what political consultants might call the point of essential contrast.

Television suits Peter Buttigieg. He is a dispassionate figure in an emotional medium. In response to ridiculousness, his face stays largely still, but his peaked eyebrows rise a notch. As a politician, Buttigieg’s great trick (it’s also a flaw) is to never take anything personally: he blinks away the noisy, slanderous business of daily politics in pursuit of what political consultants might call the point of essential contrast.

Lately, Buttigieg has been not taking things personally on Fox News. Liberals, even those who had grown tired of his dogged reasonableness, have celebrated each of his three recent appearances on the network as a tour de force and a rout. Just before the Vice-Presidential debate, last Wednesday, Buttigieg was asked on Fox News about the policy differences between Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. He replied, “Well, there’s a classic parlor game of trying to find a little bit of daylight between running mates, and if people want to play that game we could look into why an evangelical Christian like Mike Pence wants to be on a ticket with a President caught with a porn star.” Pence, President, porn—he captured the basic deal Republicans had made with power in three tight plosives. (Slayer Pete, Mary McNamara of the Los Angeles Times named this persona, brilliantly.)

It’s tempting to conclude that Buttigieg’s recent star turns on Fox News say less about him than they do about the network, whose hosts spend so much time ridiculing liberal positions that they can find themselves at a loss when those positions are presented in earnest. Last week, the “Fox and Friends” host Steve Doocy asked Buttigieg about President Trump’s choice not to participate in a virtual debate with Biden. “All of us have had to get used to virtual formats,” Buttigieg said, pointing out that parents trying to manage home learning had it much rougher than the President of the United States. He went on, “The only reason that we’re here in the first place is that the President of the United States is still contagious, as far as we know, with a deadly disease.” That clip, like his response to the question about Harris, went viral, partly because Doocy kept encouraging Buttigieg, as he usually does ideologically friendlier guests, with a series of confident-sounding local-news-anchor noises: “Sure . . . Right . . . Yeah . . . Sure . . . Right . . . Right . . . Sure.”

Fox News has always been a good venue for Buttigieg, for reasons that don’t have much to do with the dimness of its morning hosts. Last spring, a Fox audience stood at the end of a town hall with Buttigieg. “Wow! A standing ovation!” the Fox News anchor Chris Wallace said, apparently surprised by it. The network’s orientation, on both the hyperbolic evening shows and the Doocified morning ones, borrows the spirit, if not the prudity, of religious conservatives: the heartland is virtuous, and the liberal city sinful. Beamed in from Indiana, Buttigieg has a way of inverting all of that.

More here.

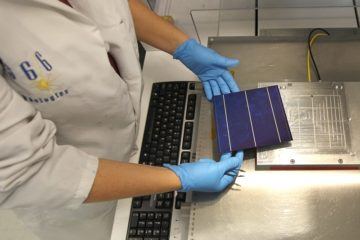

The rise of ‘ARPA-everything’ and what it means for science

Jeff Tollefson in Nature:

US President Joe Biden’s administration wants to create a US$6.5-billion agency to accelerate innovations in health and medicine — and revealed new details about the unit last month1. Dubbed ARPA-Health (ARPA-H), it is the latest in a line of global science agencies now being modelled on the renowned US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), whose work a generation ago laid the foundation for the modern Internet.

US President Joe Biden’s administration wants to create a US$6.5-billion agency to accelerate innovations in health and medicine — and revealed new details about the unit last month1. Dubbed ARPA-Health (ARPA-H), it is the latest in a line of global science agencies now being modelled on the renowned US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), whose work a generation ago laid the foundation for the modern Internet.

…The US Department of Defense established DARPA in 1958, one year after the Soviet Union launched the world’s first satellite, Sputnik 1. The goal was to avoid falling behind the Soviets, and to ensure that the United States remained a world leader in technology. DARPA was instrumental in early computing research, as well as in developing technologies such as GPS and unmanned aerial vehicles (See ‘Following in DARPA’s footsteps’).

DARPA functions differently from other major US science funding agencies, and has a leaner budget ($3.5 billion). Its roughly 100 programme managers, borrowed for stints of 3–5 years from academia or industry, have broad latitude in what they fund, and actively engage with their teams, enforcing aggressive deadlines and monitoring progress along the way. By comparison, projects funded by agencies such as the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) typically see little engagement between programme managers and the researchers they fund, beyond annual progress reports. Projects funded by these agencies also tend towards being those that are likely to succeed — and thus typically represent more incremental advances, says William Bonvillian, a policy researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge who has studied DARPA.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Where Will the Next One Come From

The next one will come from the air

It will be an overripe pumpkin

It will be the missing shoe

The next one will climb down

From the tree

When I’m asleep

The next one I will have to sow

For the next one I will have

To walk in the rain

The next one I shall not write

It will rise like bread

It will be the curse coming home

by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

from Smith College Poetry Center

Sunday, July 11, 2021

Notes on Violence

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

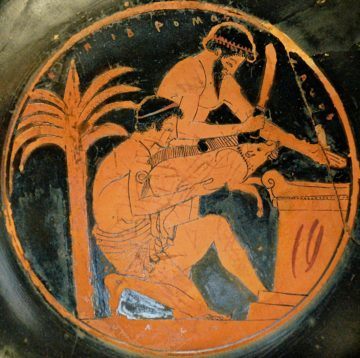

In her influential 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion”,[1] the philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson deploys a number of outlandish thought experiments. Among them is the story of a woman much like herself who gets kidnapped and, on awakening, finds she is attached by complicated life-support apparatuses to a great violinist. Her kidnappers explain when she awakens that she happens to be just so physiologically constituted as to be necessary for the violinist’s survival, and surely she agrees it is important to keep this rare musician alive, does she not? If she gets up and walks away, he will die; if she stays attached to him for nine months, they will both live. But, they acknowledge, she is of course free to go.

In her influential 1971 article, “A Defense of Abortion”,[1] the philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson deploys a number of outlandish thought experiments. Among them is the story of a woman much like herself who gets kidnapped and, on awakening, finds she is attached by complicated life-support apparatuses to a great violinist. Her kidnappers explain when she awakens that she happens to be just so physiologically constituted as to be necessary for the violinist’s survival, and surely she agrees it is important to keep this rare musician alive, does she not? If she gets up and walks away, he will die; if she stays attached to him for nine months, they will both live. But, they acknowledge, she is of course free to go.

This particular scenario is one that Thomson only invokes in the course of making another point about another category of human beings than frail adult violinists, and yet it is a passing remark about his dependency on her that has preoccupied me the longest and most profoundly: we all agree, she reasons, that the person attached to the violinist is free to get up and leave, but she is not free to slit the violinist’s throat before going. Why not? The effect is the same in both cases —the violinist dies— and indeed a case could be made that killing him swiftly is more merciful than letting him die slowly.

More here.

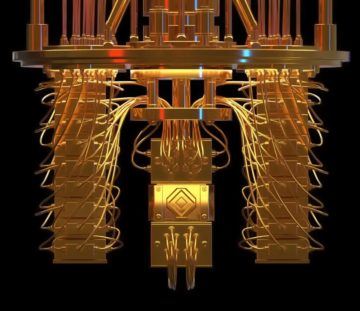

What Makes Quantum Computing So Hard to Explain?

Scott Aaronson in Quanta:

Quantum computers, you might have heard, are magical uber-machines that will soon cure cancer and global warming by trying all possible answers in different parallel universes. For 15 years, on my blog and elsewhere, I’ve railed against this cartoonish vision, trying to explain what I see as the subtler but ironically even more fascinating truth. I approach this as a public service and almost my moral duty as a quantum computing researcher. Alas, the work feels Sisyphean: The cringeworthy hype about quantum computers has only increased over the years, as corporations and governments have invested billions, and as the technology has progressed to programmable 50-qubit devices that (on certain contrived benchmarks) really can give the world’s biggest supercomputers a run for their money. And just as in cryptocurrency, machine learning and other trendy fields, with money have come hucksters.

Quantum computers, you might have heard, are magical uber-machines that will soon cure cancer and global warming by trying all possible answers in different parallel universes. For 15 years, on my blog and elsewhere, I’ve railed against this cartoonish vision, trying to explain what I see as the subtler but ironically even more fascinating truth. I approach this as a public service and almost my moral duty as a quantum computing researcher. Alas, the work feels Sisyphean: The cringeworthy hype about quantum computers has only increased over the years, as corporations and governments have invested billions, and as the technology has progressed to programmable 50-qubit devices that (on certain contrived benchmarks) really can give the world’s biggest supercomputers a run for their money. And just as in cryptocurrency, machine learning and other trendy fields, with money have come hucksters.

In reflective moments, though, I get it. The reality is that even if you removed all the bad incentives and the greed, quantum computing would still be hard to explain briefly and honestly without math. As the quantum computing pioneer Richard Feynman once said about the quantum electrodynamics work that won him the Nobel Prize, if it were possible to describe it in a few sentences, it wouldn’t have been worth a Nobel Prize.

More here.

The surprising reason a leopard was visiting a Pakistani farmer’s cow every night

UPDATE: Apologies to our readers, this video is apparently a hoax and we should have known better.

Talk of toxic masculinity puts the blame in all the wrong places

Heidi Matthews in Psyche:

As a new parent of boy/girl twins (at least as they were assigned at birth), I puzzle about the cultural pressure to scrutinise my infant son’s burgeoning masculinity lest it emerge as ‘toxic’. I catch myself watching and wondering, resisting the urge to police his interactions with his sister: He took the toy she was playing with, is this aggression that will stifle her confidence? She seems unbothered and has quickly snatched it back – phew! Is it bullying or an early form of manspreading when, both of them vying for the same object, he moves into her space and pushes her aside?

As a new parent of boy/girl twins (at least as they were assigned at birth), I puzzle about the cultural pressure to scrutinise my infant son’s burgeoning masculinity lest it emerge as ‘toxic’. I catch myself watching and wondering, resisting the urge to police his interactions with his sister: He took the toy she was playing with, is this aggression that will stifle her confidence? She seems unbothered and has quickly snatched it back – phew! Is it bullying or an early form of manspreading when, both of them vying for the same object, he moves into her space and pushes her aside?

Today, popular parenting messaging, from Instagram to The New York Times, is suspicious of and concerned about boys. ‘Boys are broken,’ we are told. Boys underperform girls in school and college, and are more likely to engage in behaviour that is harmful to both themselves and others. Boys fight, bully, take dangerous risks, and sexually harass. From school shootings to incel-inspired terrorism, white boys in particular perpetrate mass acts of violence.

More here.

Peter Zinovieff (1933 – 2021) composer, synthesizer innovator

Dilip Kumar (1922 – 2021) film star

Sunday Poem

In a Station

Once I walked through the halls of a station

Someone called your name

In the streets I heard children laughing

They all sound the same

Wonder could you ever know me

Know the reason why I live?

Is there nothing you can show me?

Life seems so little to give

Once I climbed up the face of a mountain

And ate the wild fruit there

Fell asleep until the moonlight woke me

And I could taste your hair

Isn’t everybody dreaming?

Then the voice I hear is real

Out of all the idle scheming

Can’t we have something to feel?

Once upon a time leaves me empty

Tomorrow never came

I could sing the sound of your laughter

Still I don’t know your name

Must be some way to repay you

Out of all the good you gave

If a rumor should delay you

Love seems so little to say

by Richard Manuel

from Music From Big Pink

The Band, 1968

Robert Downey Sr. (1936 – 2021) filmmaker

Cavity: A tooth can die quickly, in days, or slowly, over weeks or months or years

Danielle Geller in Guernica:

The saltwater aquarium in my new dentist’s office is its best feature. My favorite fish is a red fish with big eyes and a black stripe along its back. He has a generally grumpy demeanor, and I cannot help but feel a friendship form between us. I take photos of him and sometimes post them to Instagram. (“This red fish is my favorite fish, he is a total weirdo.”) He is popular among my friends.

The saltwater aquarium in my new dentist’s office is its best feature. My favorite fish is a red fish with big eyes and a black stripe along its back. He has a generally grumpy demeanor, and I cannot help but feel a friendship form between us. I take photos of him and sometimes post them to Instagram. (“This red fish is my favorite fish, he is a total weirdo.”) He is popular among my friends.

I am aware, though it has not been my experience, that aquariums are common features in dentist offices. (One of my childhood dentists had an arcade machine. My sister and I would race monster trucks before our appointments.) I imagine this is due to the anxiety many people feel about dental procedures. (I once had a full-blown panic attack before my wisdom tooth extraction, even though I had been given Valium to take beforehand. “I can’t do anything if you don’t stop crying,” my dentist snapped.) Aquariums aren’t cheap to maintain, but dentists or their office administrators must feel they have some beneficial or tangible impact. (In the Google reviews for my new dentist office, I find one from four years ago that reads: “Excellent service. But I went because of Dr. K—’s military service and understanding of PTSD.”) Watching fish swim lazily through a fifty-gallon tank surely has some small but significant calming effect.

The red fish doesn’t really swim. He darts from hiding place to hiding place to resting bowl, and then he crawls along with grasping, tensile fins.

…This essay is a glass aquarium. The fish, a smooth-eyed distraction.

My father is dying. Liver cancer, stage 4.

“Tell your sister not to get too excited,” he tells me in a short phone call. By excited, he does not mean thrilled. He means worked up, distraught. We are not supposed to cry about his death.

More here.

Isaac Newton’s forgotten years as a cosmopolitan Londoner

Steve Donoghue in The Christian Science Monitor:

Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. But even when Newton was performing his intellectual feats at Cambridge in the 1680s, he was eager to move on to a new life. Patricia Fara, historian of science at Cambridge University, seeks to chronicle that period in “Life after Gravity: Isaac Newton’s London Career.” In this book she presents Newton as “a metropolitan performer, a global actor who played various parts.”

Many of us tend to like our geniuses as neatly lovable caricatures. And when it comes to Isaac Newton, we tend to envision a virtually disembodied intellect who was inspired by a falling apple to revolutionize physics from the quiet of his study at Trinity College. But even when Newton was performing his intellectual feats at Cambridge in the 1680s, he was eager to move on to a new life. Patricia Fara, historian of science at Cambridge University, seeks to chronicle that period in “Life after Gravity: Isaac Newton’s London Career.” In this book she presents Newton as “a metropolitan performer, a global actor who played various parts.”

Here we have not the familiar – and almost inhuman – Newton who produced his great “Principia Mathematica” in 1687, but rather a worldly, cosmopolitan Newton: master of the Royal Mint, president of the Royal Society, member of parliament, speculator on the market, prominent man-about-town.

In many ways it’s a startling portrait, and it’s clearly intended to be. Fara is a pleasingly lively historical guide – not just to Newton’s London life, but also to the London of those decades. It’s the London of Queen Anne and William Hogarth and most of all John Dryden, and their presence wonderfully hovers over everything here. We see Newton become preoccupied with straightening out the complicated mess he’d inherited at the Royal Mint. We see him working the stock market – not always successfully, which seems at first odd about somebody who invented whole new kinds of calculus at will. And Fara’s lengthy digressions are as fascinating as her main subject – particularly the mini-biography she provides of Newton’s relative and fellow thorough-going London creature John Conduitt.

Saturday, July 10, 2021

Distributional Effects of Monetary Policy

Elham Saeidinezhad over at his website:

Elham Saeidinezhad over at his website:

Who has access to cheap credit? And who does not? Compared to small businesses and households, global banks disproportionately benefited from the Fed’s liquidity provision measures. Yet, this distributional issue at the heart of the liquidity provision programs is excluded from analyzing the recession-fighting measures’ distributional footprints. After the great financial crisis (GFC) and the Covid-19 pandemic, the Fed’s focus has been on the asset purchasing programs and their impacts on the “real variables” such as wealth. The concern has been whether the asset-purchasing measures have benefited the wealthy disproportionately by boosting asset prices. Yet, the Fed seems unconcerned about the unequal distribution of cheap credits and the impacts of its “liquidity facilities.” Such oversight is paradoxical. On the one hand, the Fed is increasing its effort to tackle the rising inequality resulting from its unconventional schemes. On the other hand, its liquidity facilities are being directed towards shadow banking rather than short-term consumers loans. A concerned Fed about inequality should monitor the distributional footprints of their policies on access to cheap debt rather than wealth accumulation.

Dismissing the effects of unequal access to cheap credit on inequality is not an intellectual mishap. Instead, it has its root in an old idea in monetary economics- the quantity theory of money– that asserts money is neutral. According to monetary neutrality, money, and credit, that cover the daily cash-flow commitments are veils. In search of the “veil of money,” the quantity theory takes two necessary steps: first, it disregards the payment systems as mere plumbing behind the transactions in the real economy.

More here.

A Friend to the Dissidents

Matt Weir in Dissent:

On the night of August 20, 1968, neighbors woke the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal and his wife, Eliška Plevová, to tell them that the Soviet Union was invading. Already their occupiers, the Soviets were now coming to put an end to the reforms of the Prague Spring. By morning, planes were flying low overhead, and soldiers and tanks filled the streets. One tank pointed its cannon directly at the offices of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers in Wenceslas Square. Hrabal, however, was eager to fulfill his duties as the best man at the wedding of his friend, the graphic artist Vladimír Boudník, in nearby Český Krumlov. “I set out in my car,” Hrabal writes in The Gentle Barbarian, “but I couldn’t get out of Prague, either through the city centre, or by using back routes, because the fraternal armies had arrived to liquidate something that was not there.” So he returned home, tried to attend a gallery show on modern American art (sorry, closed), and later relayed his troubles to his and Boudník’s mutual friend, the writer and philosopher Egon Bondy. Bondy, who called Hrabal by his nickname, Doctor, explodes in a frenzy of jealousy and admiration for Boudník:

On the night of August 20, 1968, neighbors woke the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal and his wife, Eliška Plevová, to tell them that the Soviet Union was invading. Already their occupiers, the Soviets were now coming to put an end to the reforms of the Prague Spring. By morning, planes were flying low overhead, and soldiers and tanks filled the streets. One tank pointed its cannon directly at the offices of the Union of Czechoslovak Writers in Wenceslas Square. Hrabal, however, was eager to fulfill his duties as the best man at the wedding of his friend, the graphic artist Vladimír Boudník, in nearby Český Krumlov. “I set out in my car,” Hrabal writes in The Gentle Barbarian, “but I couldn’t get out of Prague, either through the city centre, or by using back routes, because the fraternal armies had arrived to liquidate something that was not there.” So he returned home, tried to attend a gallery show on modern American art (sorry, closed), and later relayed his troubles to his and Boudník’s mutual friend, the writer and philosopher Egon Bondy. Bondy, who called Hrabal by his nickname, Doctor, explodes in a frenzy of jealousy and admiration for Boudník:

Goddamn it! That Vladimír! Will I ever have the good fortune to have so many armies set in motion because I’m getting married? The only thing that beautiful, Doctor, was when you took my greetings to Rudi Dutschke, and you went into his apartment building just as they were carrying him out after he was shot in the head. But mobilizing five armies just to stop a wedding, that’s something I’ll never fathom. Why? Because Vladimír has always attracted great events and great misfortune. That’s just how it is. Goddamn it! What amazing luck the man has!

This foolish exuberance for life and its endless variety, modern American art and lurid despotic violence alike, is characteristic of the Hrabalian universe, as is the offhand, jarring mention of the attempted assassination of Dutschke, a leftist student leader in Germany. In Hrabal’s writings, history is a portentous, dynamic background, the slaughter bench on which rests the well-told tale.

More here.

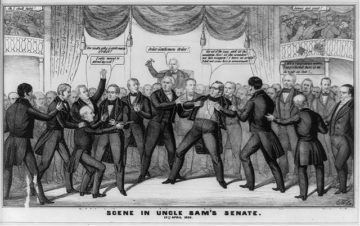

The Screaming Twenties: How Elite Overproduction May Lead to a Decade of Discord in the United States

Gideon Jones in Strife:

Gideon Jones in Strife:

One of the great stories about the United States in recent years has been the rise of political polarisation and instability. Though the growing strife at the heart of the nation has been in the making for decades, the last year alone has seen the Covid Crisis, the death of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter movement, as well as an election process that climaxed with the storming of the U.S Capitol Building. To any observer, it is apparent that these events have continued to exacerbate cleavages in American political life, and it seems that such divides will not be bridged anytime soon. The great fear is that US in the 21st Century may be facing a period of political instability, competing radical ideologies and ever-widening inequality. The last century in the US saw a post-World War One resurgence in the Roaring of the 1920s- will the 2020s in contrast see us dragged Screaming through the decade?

The United States is not alone in facing this problem. France has faced nationwide protests since 2018 with the gilets jaune movement, whilst the United Kingdom faced political paralysis and partisan infighting with the Brexit referendum (while Northern Ireland faced some of the worst riots its seen in years in part due to the Irish Sea Border). Many hypotheses have been put forward about the source of the discontent that has been rising in the United States and the rest of the Western world. Yet no theorisation, I believe, can claim to be as unique or intriguing as that of elite overproduction, and there is reason to believe that the 2020s will continue to see increasing political instability because of it.

Peter Turchin, whose work has been gaining increased recognition as of late, uses Structural Demographic Theory alongside a way of studying the long-term dynamics that create conditions for political stability, and in turn, political disintegration, and uses this to analyse history. Turchin proposes that all structural-demographic variables that influence the (in)stability of a given society are encompassed within three forces: the population, the state, and the elites (with each of these categories subject to change in response to structural shifts).

More here.

All Money Is ‘Fiat Money,’ Most Money Is ‘Credit Money’

Robert Hockett in Forbes:

Robert Hockett in Forbes:

There seems to be some confusion afoot about what ‘fiat currencies’ are, whether the dollar is one of them, and whether it ought or ought not to be. Much of this stems from latterday gold enthusiasts like Peter Schiff and, ironically, what I call his Cryptopian antagonists.

Goldbugs use ‘fiat’ as a term of opprobrium, suggesting that money by decree is a threat to liberty and currency value alike thanks to the power conferred on the state or its agent – the central banker. Cryptopians talk the same talk, thereby infuriating the likes of Schiff.

Schiff’s beef with the Cryptopians is that they replace what he views as one valueless instrument – the fiat dollar – with another, the so-called crypto asset – neither of which bears any ‘intrinsic’ value. Only substances like gold, Schiff maintains in his guise as a latterday exponent of ‘commodity money,’ retains that.