Andru Okun in The Baffler:

Concerns were raised about the 2020 hurricane season even before it officially began, as above-average air and water temperatures in the Gulf signaled an elevated chance of supercharged storms. When Hurricane Laura struck the southwest coast of Louisiana late last August, it carried with it 150 mile-per-hour winds and a storm surge of roughly ten feet. It was the strongest hurricane to hit Louisiana since 1856, causing around $17.5 billion in damages and killing thirty-three. Six weeks later, the same area was hit by yet another powerful hurricane that dumped fifteen inches of rain onto the storm-ravaged city of Lake Charles. Recently, climate researchers looked at over ninety peer-reviewed scientific articles on tropical cyclones and concluded that anthropogenic global warming was—to no one’s surprise—making storms more powerful. Meanwhile, Louisiana continues to heat up, with cities throughout the state experiencing up to an extra month of extreme heat when compared to fifty years ago.

Concerns were raised about the 2020 hurricane season even before it officially began, as above-average air and water temperatures in the Gulf signaled an elevated chance of supercharged storms. When Hurricane Laura struck the southwest coast of Louisiana late last August, it carried with it 150 mile-per-hour winds and a storm surge of roughly ten feet. It was the strongest hurricane to hit Louisiana since 1856, causing around $17.5 billion in damages and killing thirty-three. Six weeks later, the same area was hit by yet another powerful hurricane that dumped fifteen inches of rain onto the storm-ravaged city of Lake Charles. Recently, climate researchers looked at over ninety peer-reviewed scientific articles on tropical cyclones and concluded that anthropogenic global warming was—to no one’s surprise—making storms more powerful. Meanwhile, Louisiana continues to heat up, with cities throughout the state experiencing up to an extra month of extreme heat when compared to fifty years ago.

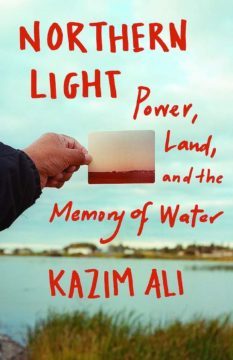

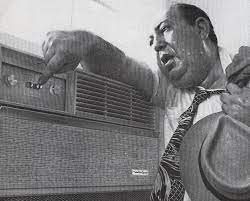

As I began writing this, the New Orleans area was under an excessive heat warning, with a possibility of “feels like” temperatures nearing 110 degrees. I posted up in front of an air-conditioner—a window unit, set to 82 degrees. I’d describe it as “comfortable,” but what does that even mean? Much of Eric Dean Wilson’s new far-reaching study of air-conditioning—After Cooling: On Freon, Global Warming, and The Terrible Cost of Comfort—deals directly with this question. While it may not be a surprise to learn that Euro-American standards of comfort have been largely dictated by rich and sweaty white men, how exactly this standard was set makes for a fascinating narrative of technological innovation and environmental destruction.

…While air-conditioning became normalized in industry and education by the 1920s, Wilson notes that “the idea of air-conditioning for public and private comfort remained absurd”—even for the wealthy. Early model air-conditioners tended to be clumsy and dangerous, using toxic natural refrigerants like ammonia that could corrode copper piping and leak, thereby infusing a space with the smell of urine and potentially killing anyone who remained inside. For comfort cooling to achieve mainstream acceptance, safer, more efficient systems needed to be created.

Enter chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), the synthetic refrigerant better known as Freon—which facilitated the widespread adoption of mechanical cooling and massively fucked up the planet in the process.

More here.

Byung-Chul Han tells us in The Disappearance of Rituals, that ‘symbolic perception, as recognition, is the perception of the permanent’. In a world that often seems to be determined by change, by transient experiences, names are an anomaly. They are stubborn things, pushing back against the relentless march of time. Ages change, job titles, citizenship, but names we carry with us. In defiance of a life in constant motion. When we name newborns, we are trying to locate them in the world by carving out their distinction from others, as absolute immutable entities. Some part of that distinction will follow them through the trajectory of their life. Names endure, names remain.

Byung-Chul Han tells us in The Disappearance of Rituals, that ‘symbolic perception, as recognition, is the perception of the permanent’. In a world that often seems to be determined by change, by transient experiences, names are an anomaly. They are stubborn things, pushing back against the relentless march of time. Ages change, job titles, citizenship, but names we carry with us. In defiance of a life in constant motion. When we name newborns, we are trying to locate them in the world by carving out their distinction from others, as absolute immutable entities. Some part of that distinction will follow them through the trajectory of their life. Names endure, names remain.

I’d like to set up an experiment to chart the sadness—try to find out where it comes from, where it goes—to trace it, in that melody (whichever variation) as it threads across Manhattan from the Lower East Side straight across the river, more or less west, into the suburbs of New Jersey and whatever lies beyond. This would require, I’m guessing, maybe a hundred saxophonists stationed along the route on tops of buildings, water towers, farther out on people’s porches (with permission), empty parking lots, at intervals determined by the limits of their mutual audibility under variable conditions in the middle of the night, so each would strain a bit to pick it up and pass it on in step until they’re going all at once and all strung out along this fraying thread of melody for hours, with relievers in reserve. There’s bound to be some drifting in and out of phase, attenuation of the tempo, of the sadness for that matter, of the waveform, what I think of as the waveform of the whole thing as it comes across the river losing amplitude and sharpness, rounding, flattening, and diffusing into neighborhoods where maybe it just sort of washes over people staying up to hear it or, awakened, wondering what is that out there so faint and faintly echoed, faintly sad but not so sad that you can’t close your eyes again and drift right back to sleep.

I’d like to set up an experiment to chart the sadness—try to find out where it comes from, where it goes—to trace it, in that melody (whichever variation) as it threads across Manhattan from the Lower East Side straight across the river, more or less west, into the suburbs of New Jersey and whatever lies beyond. This would require, I’m guessing, maybe a hundred saxophonists stationed along the route on tops of buildings, water towers, farther out on people’s porches (with permission), empty parking lots, at intervals determined by the limits of their mutual audibility under variable conditions in the middle of the night, so each would strain a bit to pick it up and pass it on in step until they’re going all at once and all strung out along this fraying thread of melody for hours, with relievers in reserve. There’s bound to be some drifting in and out of phase, attenuation of the tempo, of the sadness for that matter, of the waveform, what I think of as the waveform of the whole thing as it comes across the river losing amplitude and sharpness, rounding, flattening, and diffusing into neighborhoods where maybe it just sort of washes over people staying up to hear it or, awakened, wondering what is that out there so faint and faintly echoed, faintly sad but not so sad that you can’t close your eyes again and drift right back to sleep. Memoria is a beautiful and mysterious movie, slow cinema that decelerates your heartbeat.

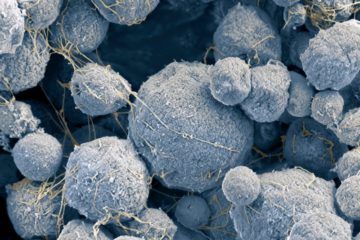

Memoria is a beautiful and mysterious movie, slow cinema that decelerates your heartbeat.  The Borg have landed — or, at least, researchers have discovered their counterparts here on Earth. Scientists analysing samples from muddy sites in the western United States have found novel DNA structures that seem to scavenge and ‘assimilate’ genes from microorganisms in their environment, much like the fictional Star Trek ‘Borg’ aliens who assimilate the knowledge and technology of other species. These extra-long DNA strands, which the scientists named in honour of the aliens, join a diverse collection of genetic structures — circular plasmids, for example — known as extrachromosomal elements (ECEs). Most microbes have one or two chromosomes that encode their primary genetic blueprint. But they can host, and often share between them, many distinct ECEs. These carry non-essential but useful genes, such as those for antibiotic resistance.

The Borg have landed — or, at least, researchers have discovered their counterparts here on Earth. Scientists analysing samples from muddy sites in the western United States have found novel DNA structures that seem to scavenge and ‘assimilate’ genes from microorganisms in their environment, much like the fictional Star Trek ‘Borg’ aliens who assimilate the knowledge and technology of other species. These extra-long DNA strands, which the scientists named in honour of the aliens, join a diverse collection of genetic structures — circular plasmids, for example — known as extrachromosomal elements (ECEs). Most microbes have one or two chromosomes that encode their primary genetic blueprint. But they can host, and often share between them, many distinct ECEs. These carry non-essential but useful genes, such as those for antibiotic resistance. One morning a few weeks ago, I sent my friend a Proust text. It was a photo of a page from Swann’s Way, and it took several attempts for me to capture the near-page-length sentence in its entirety. Next to me, my 2-year-old daughter slowly guided a spoonful of oatmeal into her mouth, noticing my struggle. “Daddy, what are you doing?” she asked. The answer: being insufferable. My friend’s response shortly thereafter confirmed this: “It’s too early for me to follow this sentence.”

One morning a few weeks ago, I sent my friend a Proust text. It was a photo of a page from Swann’s Way, and it took several attempts for me to capture the near-page-length sentence in its entirety. Next to me, my 2-year-old daughter slowly guided a spoonful of oatmeal into her mouth, noticing my struggle. “Daddy, what are you doing?” she asked. The answer: being insufferable. My friend’s response shortly thereafter confirmed this: “It’s too early for me to follow this sentence.” Once upon a time, I decided to start answering the question “Where are you from?” with “The middle of the Pacific Ocean.” I never followed through, though I still think it’s a good answer. I have spent so much of my life bouncing back and forth between the United States and India that, for me, the concept of home is more like a stationary probability distribution — a phrase that I filched from a statistics paper once, and which is likely to make less sense to most people than “the middle of the Pacific Ocean.” After all, the latter at least counts as a place.

Once upon a time, I decided to start answering the question “Where are you from?” with “The middle of the Pacific Ocean.” I never followed through, though I still think it’s a good answer. I have spent so much of my life bouncing back and forth between the United States and India that, for me, the concept of home is more like a stationary probability distribution — a phrase that I filched from a statistics paper once, and which is likely to make less sense to most people than “the middle of the Pacific Ocean.” After all, the latter at least counts as a place. The summer wasn’t meant to be like this. By April, Greene County, in southwestern Missouri, seemed to be past

The summer wasn’t meant to be like this. By April, Greene County, in southwestern Missouri, seemed to be past  In October 2018,

In October 2018,  Concerns were raised about the 2020 hurricane season even before it officially began, as above-average air and water temperatures in the Gulf signaled an elevated chance of supercharged storms. When Hurricane Laura struck the southwest coast of Louisiana late last August, it carried with it 150 mile-per-hour winds and a storm surge of roughly ten feet. It was the strongest hurricane to hit Louisiana since 1856, causing around $17.5 billion in damages and killing thirty-three. Six weeks later, the same area was hit by yet another powerful hurricane that dumped fifteen inches of rain onto the storm-ravaged city of Lake Charles. Recently, climate researchers looked at over ninety peer-reviewed scientific articles on tropical cyclones and concluded that anthropogenic global warming was—to no one’s surprise—making storms more powerful. Meanwhile, Louisiana continues to heat up, with cities throughout the state experiencing up to an extra month of extreme heat when compared to fifty years ago.

Concerns were raised about the 2020 hurricane season even before it officially began, as above-average air and water temperatures in the Gulf signaled an elevated chance of supercharged storms. When Hurricane Laura struck the southwest coast of Louisiana late last August, it carried with it 150 mile-per-hour winds and a storm surge of roughly ten feet. It was the strongest hurricane to hit Louisiana since 1856, causing around $17.5 billion in damages and killing thirty-three. Six weeks later, the same area was hit by yet another powerful hurricane that dumped fifteen inches of rain onto the storm-ravaged city of Lake Charles. Recently, climate researchers looked at over ninety peer-reviewed scientific articles on tropical cyclones and concluded that anthropogenic global warming was—to no one’s surprise—making storms more powerful. Meanwhile, Louisiana continues to heat up, with cities throughout the state experiencing up to an extra month of extreme heat when compared to fifty years ago. People who want to deplatform a speaker or deep-six a book love to point out that the First Amendment only applies to government. But socially and culturally, the notion that people have a right to say what they think and read what they want is much broader than that. That is why common dismissals—you can still get the book online, the speaker has plenty of other ways to express herself, books go out of print all the time—sound flip.

People who want to deplatform a speaker or deep-six a book love to point out that the First Amendment only applies to government. But socially and culturally, the notion that people have a right to say what they think and read what they want is much broader than that. That is why common dismissals—you can still get the book online, the speaker has plenty of other ways to express herself, books go out of print all the time—sound flip. In any normal summer, Spain’s famous Playa de la Castilla – a perfect 20km (12 mile) long stretch of sand backed by the Doñana nature reserve and close to the resort of Matalascañas, Huelva – would have been covered by the footprints of visiting tourists. But in June 2020 with international flights banned due to Covid-19, the beach was uncharacteristically quiet. Two biologists – María Dolores Cobo and Ana Mateos – who were strolling along the peaceful beach, nonetheless found many footprints. These, however, were made by a very different kind of visitor.

In any normal summer, Spain’s famous Playa de la Castilla – a perfect 20km (12 mile) long stretch of sand backed by the Doñana nature reserve and close to the resort of Matalascañas, Huelva – would have been covered by the footprints of visiting tourists. But in June 2020 with international flights banned due to Covid-19, the beach was uncharacteristically quiet. Two biologists – María Dolores Cobo and Ana Mateos – who were strolling along the peaceful beach, nonetheless found many footprints. These, however, were made by a very different kind of visitor. Simon Torracinta in Boston Review:

Simon Torracinta in Boston Review: