Janique Vigier in Bookforum:

SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation easily (attacks on her memoirs, particularly the divorce tale Aftermath, were vicious), nor at a young age (she is now fifty-four).

SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation easily (attacks on her memoirs, particularly the divorce tale Aftermath, were vicious), nor at a young age (she is now fifty-four).

Second Place, Cusk’s latest novel, begins from the perch of moral certainty, and never quite lets go. A psychosexual drama with no sex, the book revolves around two characters, referred to only as L and M. L is a male artist, M a female patron. The novel centers around the questions these differences reveal. Or, closer to the truth: these questions and differences reveal Cusk’s predetermined moral universe. Questions are illusory; there are deterministic stances. The standpoint of the main characters reflects this. L, fey and ascetic, is a thinly disguised version of D. H. Lawrence, whom Cusk has called her mentor. L is a painter, not a writer, but the specter of Male Genius is made clear. His foil, M, the writer-narrator, reveres his paintings, seeing him, by extension, as a kind of oracle. She makes the natural assumption and casual error of conflating the virtues of the work with the character of the artist. Cusk’s own devotion to Lawrence makes these metatextual tricks all the more fraught. Is there a more intimate and controlling way to pay homage to your literary idol than by turning him into a fictional character?

It’s a funny time to write a novel about Lawrence, though not necessarily more so than any other: too romantic to be modern, accused by his contemporaries of being a pornographer—that is, part of the avant-garde—he has never been contemporary, not even in his own time. A man whose tragedy, according to Angela Carter, was that “he thought he was a man,” a pious man who wrote frankly about sex, Lawrence suffered his aloneness. Poor, childless, mostly itinerant, he shares little biographical similarity with Cusk, who has turned her children, her career success, and her home into subjects for her fiction. What the two writers do share is a basic and unassailable belief in the individual, a belief that underwrites their obsessive preoccupation with will, intuition, and transformation. Above all it’s women—as question and problem—that drive their work and fetter their hearts. How can women give voice to themselves? What can love look like? And freedom?

More here.

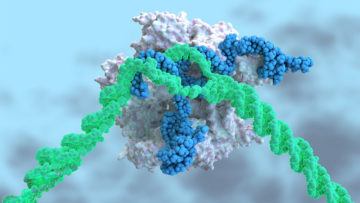

Natural selection has done a pretty good job at creating a wide variety of living species, but we humans can’t help but wonder whether we could do better. Using existing genomes as a starting point, biologists are getting increasingly skilled at designing organisms of our own imagination. But to do that, we need a better understanding of what different genes in our DNA actually do. Elizabeth Strychalski and collaborators recently announced the construction of a synthetic microbial organism that self-reproduces just like a normal unicellular creature. This work will help us understand the roles of genes in reproduction, one step on the road to making DNA molecules and artificial cells that will perform a variety of medical and biological tasks.

Natural selection has done a pretty good job at creating a wide variety of living species, but we humans can’t help but wonder whether we could do better. Using existing genomes as a starting point, biologists are getting increasingly skilled at designing organisms of our own imagination. But to do that, we need a better understanding of what different genes in our DNA actually do. Elizabeth Strychalski and collaborators recently announced the construction of a synthetic microbial organism that self-reproduces just like a normal unicellular creature. This work will help us understand the roles of genes in reproduction, one step on the road to making DNA molecules and artificial cells that will perform a variety of medical and biological tasks.

Herrington, a Dutch sustainability researcher and adviser to the Club of Rome, a Swiss thinktank, has

Herrington, a Dutch sustainability researcher and adviser to the Club of Rome, a Swiss thinktank, has  Julia Ann Moore (1847–1920), the “Sweet Singer of Michigan,” was one of the worst American poets of the nineteenth century, or perhaps of any century. Her ear for the clunky inverted phrase, or the just-miss rhyme, generated bad verse on patriotic themes and historical subjects, but what really inspired her was obituary poetry, a genre which thrived all through the nineteenth century, and which drew steadily on the talent—or lack of talent—of local amateur commemorative poets. And her specialty within a specialty was obituary poetry for those dying young: “Every time one of my darlings died, or any of the neighbor’s children were buried, I just wrote a poem on their death,” she told an interviewer from the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean in 1878. “That’s the way I got started.”

Julia Ann Moore (1847–1920), the “Sweet Singer of Michigan,” was one of the worst American poets of the nineteenth century, or perhaps of any century. Her ear for the clunky inverted phrase, or the just-miss rhyme, generated bad verse on patriotic themes and historical subjects, but what really inspired her was obituary poetry, a genre which thrived all through the nineteenth century, and which drew steadily on the talent—or lack of talent—of local amateur commemorative poets. And her specialty within a specialty was obituary poetry for those dying young: “Every time one of my darlings died, or any of the neighbor’s children were buried, I just wrote a poem on their death,” she told an interviewer from the Chicago Daily Inter Ocean in 1878. “That’s the way I got started.” It’s not hard to see what first drew Barnes and de Kooning to Soutine. His arresting portraits from the 1910s and ’20s, the first works on view, reveal both a wry distrust of himself and a sure confidence in his capacity to observe and render the inner lives of other people. In his laconic 1918 Self-Portrait, he’s clothed in a rumpled blue smock and stares straight ahead at the viewer; another portrait (evidently by Soutine) covers his right shoulder and fills the left side of the frame. Soutine is clearly channeling similar works by artists like Velázquez and Rembrandt, which he regularly studied in his frequent trips to the Louvre. Yet his own Self-Portrait, geometrically and chromatically centered on his puffy, blood-red lips, also evokes the grotesque—so called because it traditionally portrayed subjects best kept out of sight. After Barnes helped make him famous, Soutine began to appear at Parisian salons in elegant clothes (indeed, Polish writer and painter Józef Czapski calls attention to his “expensive felt hats and gleaming leather boots”), yet he remained something of an outsider.

It’s not hard to see what first drew Barnes and de Kooning to Soutine. His arresting portraits from the 1910s and ’20s, the first works on view, reveal both a wry distrust of himself and a sure confidence in his capacity to observe and render the inner lives of other people. In his laconic 1918 Self-Portrait, he’s clothed in a rumpled blue smock and stares straight ahead at the viewer; another portrait (evidently by Soutine) covers his right shoulder and fills the left side of the frame. Soutine is clearly channeling similar works by artists like Velázquez and Rembrandt, which he regularly studied in his frequent trips to the Louvre. Yet his own Self-Portrait, geometrically and chromatically centered on his puffy, blood-red lips, also evokes the grotesque—so called because it traditionally portrayed subjects best kept out of sight. After Barnes helped make him famous, Soutine began to appear at Parisian salons in elegant clothes (indeed, Polish writer and painter Józef Czapski calls attention to his “expensive felt hats and gleaming leather boots”), yet he remained something of an outsider. Time after time, Segnit meets the most skilled practitioners, the most enlightened minds on the planet, and time after time they fail to find the words. Early on we are introduced to Sister Nectaria, an elderly nun who has lived at a remote monastery on a Greek island since the age of eleven. She is, says Segnit, ‘a living, breathing, invocation of god’. But she finds his questions irritating, or invasive, or beside the point. Later, we meet Tenzin Palmo, a British woman formerly known as Diane Perry who spent twelve years meditating alone in a cave in the Himalayas. ‘I hardly remember any of it,’ she insists. ‘At the time it seemed very ordinary.’

Time after time, Segnit meets the most skilled practitioners, the most enlightened minds on the planet, and time after time they fail to find the words. Early on we are introduced to Sister Nectaria, an elderly nun who has lived at a remote monastery on a Greek island since the age of eleven. She is, says Segnit, ‘a living, breathing, invocation of god’. But she finds his questions irritating, or invasive, or beside the point. Later, we meet Tenzin Palmo, a British woman formerly known as Diane Perry who spent twelve years meditating alone in a cave in the Himalayas. ‘I hardly remember any of it,’ she insists. ‘At the time it seemed very ordinary.’

Philosophers aren’t the only ones who love wisdom. Everyone, philosopher or not, loves her own wisdom: the wisdom she has or takes herself to have. What distinguishes the philosopher is loving the wisdom she doesn’t have. Philosophy is, therefore, a form of humility: being aware that you lack what is of supreme importance. There may be no human being who exemplified this form of humility more perfectly than Socrates. It is no coincidence that he is considered the first philosopher within the Western canon.

Philosophers aren’t the only ones who love wisdom. Everyone, philosopher or not, loves her own wisdom: the wisdom she has or takes herself to have. What distinguishes the philosopher is loving the wisdom she doesn’t have. Philosophy is, therefore, a form of humility: being aware that you lack what is of supreme importance. There may be no human being who exemplified this form of humility more perfectly than Socrates. It is no coincidence that he is considered the first philosopher within the Western canon. Today marks the 133rd anniversary of the birth of Raymond Chandler, patron saint of Los Angeles noir and perhaps the most famous crime fiction writer of all time. Each of his nine novels, from The Big Sleep (1939) to the posthumously published Playback (1953), center around iconic gumshoe Philip Marlowe—Chandler’s wisecracking, whiskey-drinking, tough-as-an-old-boot fictional private investigator so memorably portrayed on screen by (among many, many others)

Today marks the 133rd anniversary of the birth of Raymond Chandler, patron saint of Los Angeles noir and perhaps the most famous crime fiction writer of all time. Each of his nine novels, from The Big Sleep (1939) to the posthumously published Playback (1953), center around iconic gumshoe Philip Marlowe—Chandler’s wisecracking, whiskey-drinking, tough-as-an-old-boot fictional private investigator so memorably portrayed on screen by (among many, many others)  Trees that communicate, care for one another and foster cooperative communities have captured the popular imagination, most notably in Suzanne Simard’s

Trees that communicate, care for one another and foster cooperative communities have captured the popular imagination, most notably in Suzanne Simard’s  Self-regarding economics departments at prestigious academic institutions no longer bother to teach the history of economic thought – a field that I studied at Yale University in 1977, forever compromising my academic career. Why was the topic abandoned – and even shunned and mocked? Students with a skeptical turn of mind would not be wrong to suspect that it was for scandalous reasons (as when, in past centuries, inconvenient aunts were locked away in garrets).

Self-regarding economics departments at prestigious academic institutions no longer bother to teach the history of economic thought – a field that I studied at Yale University in 1977, forever compromising my academic career. Why was the topic abandoned – and even shunned and mocked? Students with a skeptical turn of mind would not be wrong to suspect that it was for scandalous reasons (as when, in past centuries, inconvenient aunts were locked away in garrets). SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation easily (attacks on her memoirs, particularly the divorce tale Aftermath, were vicious), nor at a young age (she is now fifty-four).

SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation easily (attacks on her memoirs, particularly the divorce tale Aftermath, were vicious), nor at a young age (she is now fifty-four). I

I Steven Weinberg was, perhaps, the last truly towering figure of 20th-century physics. In 1967, he wrote a

Steven Weinberg was, perhaps, the last truly towering figure of 20th-century physics. In 1967, he wrote a

Prabhat Patnaik in Boston Review:

Prabhat Patnaik in Boston Review: