Rachel Aviv in The New Yorker:

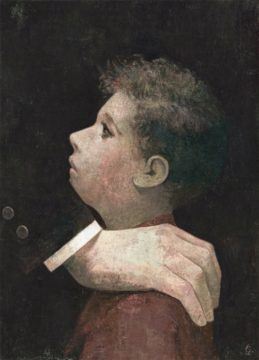

In 2017, a German man who goes by the name Marco came across an article in a Berlin newspaper with a photograph of a professor he recognized from childhood. The first thing he noticed was the man’s lips. They were thin, almost nonexistent, a trait that Marco had always found repellent. He was surprised to read that the professor, Helmut Kentler, had been one of the most influential sexologists in Germany. The article described a new research report that had investigated what was called the “Kentler experiment.” Beginning in the late sixties, Kentler had placed neglected children in foster homes run by pedophiles. The experiment was authorized and financially supported by the Berlin Senate. In a report submitted to the Senate, in 1988, Kentler had described it as a “complete success.”

In 2017, a German man who goes by the name Marco came across an article in a Berlin newspaper with a photograph of a professor he recognized from childhood. The first thing he noticed was the man’s lips. They were thin, almost nonexistent, a trait that Marco had always found repellent. He was surprised to read that the professor, Helmut Kentler, had been one of the most influential sexologists in Germany. The article described a new research report that had investigated what was called the “Kentler experiment.” Beginning in the late sixties, Kentler had placed neglected children in foster homes run by pedophiles. The experiment was authorized and financially supported by the Berlin Senate. In a report submitted to the Senate, in 1988, Kentler had described it as a “complete success.”

Marco had grown up in foster care, and his foster father had frequently taken him to Kentler’s home. Now he was thirty-four, with a one-year-old daughter, and her meals and naps structured his days. After he read the article, he said, “I just pushed it aside. I didn’t react emotionally. I did what I do every day: nothing, really. I sat around in front of the computer.”

Marco looks like a movie star—he is tanned, with a firm jaw, thick dark hair, and a long, symmetrical face. As an adult, he has cried only once. “If someone were to die in front of me, I would of course want to help them, but it wouldn’t affect me emotionally,” he told me. “I have a wall, and emotions just hit against it.” He lived with his girlfriend, a hairdresser, but they never discussed his childhood. He was unemployed. Once, he tried to work as a mailman, but after a few days he quit, because whenever a stranger made an expression that reminded him of his foster father, an engineer named Fritz Henkel, he had the sensation that he was not actually alive, that his heart had stopped beating, and that the color had drained from the world. When he tried to speak, it felt as if his voice didn’t belong to him.

More here.

Three ideas that are central to all Orwell’s subsequent, serious writing were formed in Spain. First, that socialism works. Second, that socialism works, but beware, for it can take an authoritarian turn. (Homage to Catalonia in part tells a similar story to Animal Farm ‑ the utopia betrayed from within when its leaders start to suit themselves.) Third, that those who betray lie brazenly, weaving an elaborate web of self-serving falsehood. “[I]n Spain,” wrote Orwell in the 1942 “Looking Back on the Spanish War”, “for the first time, I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts, not even the relationship which is implied in an ordinary lie. I saw great battles reported where there had been no fighting, and complete silence where hundreds of men had been killed … This kind of thing is frightening to me, because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading from the world.”

Three ideas that are central to all Orwell’s subsequent, serious writing were formed in Spain. First, that socialism works. Second, that socialism works, but beware, for it can take an authoritarian turn. (Homage to Catalonia in part tells a similar story to Animal Farm ‑ the utopia betrayed from within when its leaders start to suit themselves.) Third, that those who betray lie brazenly, weaving an elaborate web of self-serving falsehood. “[I]n Spain,” wrote Orwell in the 1942 “Looking Back on the Spanish War”, “for the first time, I saw newspaper reports which did not bear any relation to the facts, not even the relationship which is implied in an ordinary lie. I saw great battles reported where there had been no fighting, and complete silence where hundreds of men had been killed … This kind of thing is frightening to me, because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading from the world.”

So what should we do in such a predicament? We should above all avoid the common wisdom according to which the lesson of the ecological crises is that we are part of nature, not its center, so we have to change our way of life — limit our individualism, develop new solidarity, and accept our modest place among life on our planet. Or, as Judith Butler put it, “An inhabitable world for humans depends on a flourishing earth that does not have humans at its center. We oppose environmental toxins not only so that we humans can live and breathe without fear of being poisoned, but also because the water and the air must have lives that are not centered on our own.”

So what should we do in such a predicament? We should above all avoid the common wisdom according to which the lesson of the ecological crises is that we are part of nature, not its center, so we have to change our way of life — limit our individualism, develop new solidarity, and accept our modest place among life on our planet. Or, as Judith Butler put it, “An inhabitable world for humans depends on a flourishing earth that does not have humans at its center. We oppose environmental toxins not only so that we humans can live and breathe without fear of being poisoned, but also because the water and the air must have lives that are not centered on our own.”

Efforts to understand cardiac disease progression and develop therapeutic tissues that can repair the human heart are just a few areas of focus for the Feinberg research group at Carnegie Mellon University. The group’s latest dynamic model, created in partnership with collaborators in the Netherlands, mimics physiologic loads on engineering heart muscle tissues, yielding an unprecedented view of how genetics and mechanical forces contribute to heart muscle function.

Efforts to understand cardiac disease progression and develop therapeutic tissues that can repair the human heart are just a few areas of focus for the Feinberg research group at Carnegie Mellon University. The group’s latest dynamic model, created in partnership with collaborators in the Netherlands, mimics physiologic loads on engineering heart muscle tissues, yielding an unprecedented view of how genetics and mechanical forces contribute to heart muscle function. Unlike talk of, say, badgers or ermine, talk of beavers seems always to be the overture to a joke. So powerful is the infection of the cloud of its strange humor that the beaver is no doubt in part to blame for the widespread habit, among certain unkind Americans, of smirking at the mere mention of Canada. Nor is it the vulgar euphemism, common in North American English and immortalized in Les Claypool’s heartfelt ode, “

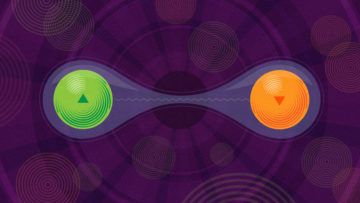

Unlike talk of, say, badgers or ermine, talk of beavers seems always to be the overture to a joke. So powerful is the infection of the cloud of its strange humor that the beaver is no doubt in part to blame for the widespread habit, among certain unkind Americans, of smirking at the mere mention of Canada. Nor is it the vulgar euphemism, common in North American English and immortalized in Les Claypool’s heartfelt ode, “ We take for granted that an event in one part of the world cannot instantly affect what happens far away. This principle, which physicists call locality, was long regarded as a bedrock assumption about the laws of physics. So when Albert Einstein and two colleagues showed in 1935 that quantum mechanics permits “spooky action at a distance,” as Einstein put it, this feature of the theory seemed highly suspect. Physicists wondered whether quantum mechanics was missing something.

We take for granted that an event in one part of the world cannot instantly affect what happens far away. This principle, which physicists call locality, was long regarded as a bedrock assumption about the laws of physics. So when Albert Einstein and two colleagues showed in 1935 that quantum mechanics permits “spooky action at a distance,” as Einstein put it, this feature of the theory seemed highly suspect. Physicists wondered whether quantum mechanics was missing something. It has been four decades since neoliberal globalization began to reshape the world order. During this time, its agenda has

It has been four decades since neoliberal globalization began to reshape the world order. During this time, its agenda has  So here is my ask. I want fiction by “men” in which they go into real detail about the internal mechanics of their own masculinity. I want evidence of that interiority on the page. Does it exist. All I’ve ever seen is silence or violence. I mean he’s perpetually doing it, the performance of being a man in writing, but he concomitantly refuses its existence except when there’s a glitch, meaning a woman, a queer, or an oddly behaving man. It’s like the only way a man ever talks about gender at all is by talking about them. Never talking about how it is to be a man.

So here is my ask. I want fiction by “men” in which they go into real detail about the internal mechanics of their own masculinity. I want evidence of that interiority on the page. Does it exist. All I’ve ever seen is silence or violence. I mean he’s perpetually doing it, the performance of being a man in writing, but he concomitantly refuses its existence except when there’s a glitch, meaning a woman, a queer, or an oddly behaving man. It’s like the only way a man ever talks about gender at all is by talking about them. Never talking about how it is to be a man. TM: The epigraph to your poem “Cotton Candy” is from John Donne: “To go to heaven, we make heaven come to us.” In its original context, the line appears: “All their proportion’s lame, it sinks, it swells; / For of meridians and parallels / Man hath weaved out a net, and this net thrown / Upon the heavens, and now they are his own. / Loth to go up the hill, or labour thus / To go to heaven, we make heaven come to us. / We spur, we rein the stars, and in their race / They’re diversely content to obey our pace.” I love your epigraphic eye here. Who is Donne to you, as both poet and legacy? Why choose these lines in particular from his poem?

TM: The epigraph to your poem “Cotton Candy” is from John Donne: “To go to heaven, we make heaven come to us.” In its original context, the line appears: “All their proportion’s lame, it sinks, it swells; / For of meridians and parallels / Man hath weaved out a net, and this net thrown / Upon the heavens, and now they are his own. / Loth to go up the hill, or labour thus / To go to heaven, we make heaven come to us. / We spur, we rein the stars, and in their race / They’re diversely content to obey our pace.” I love your epigraphic eye here. Who is Donne to you, as both poet and legacy? Why choose these lines in particular from his poem? In 2017, a German man who goes by the name Marco came across an article in a Berlin newspaper with a photograph of a professor he recognized from childhood. The first thing he noticed was the man’s lips. They were thin, almost nonexistent, a trait that Marco had always found repellent. He was surprised to read that the professor, Helmut Kentler, had been one of the most influential sexologists in Germany. The article described a new research report that had investigated what was called the “Kentler experiment.” Beginning in the late sixties, Kentler had placed neglected children in foster homes run by pedophiles. The experiment was authorized and financially supported by the Berlin Senate. In a report submitted to the Senate, in 1988, Kentler had described it as a “complete success.”

In 2017, a German man who goes by the name Marco came across an article in a Berlin newspaper with a photograph of a professor he recognized from childhood. The first thing he noticed was the man’s lips. They were thin, almost nonexistent, a trait that Marco had always found repellent. He was surprised to read that the professor, Helmut Kentler, had been one of the most influential sexologists in Germany. The article described a new research report that had investigated what was called the “Kentler experiment.” Beginning in the late sixties, Kentler had placed neglected children in foster homes run by pedophiles. The experiment was authorized and financially supported by the Berlin Senate. In a report submitted to the Senate, in 1988, Kentler had described it as a “complete success.” Blaise Pascal was a renowned French polymath of the 17th century, scientist, philosopher, mathematician, inventor, and later in life a theologian. Among his many contributions was an attempt to prove by logical means the existence of God, which came to be known as Pascal’s Wager. Stated simply, Pascal reasoned that not believing in God, if there was one, would damn you to eternal suffering. Conversely, believing in God, if there wasn’t one, would cost you little in this life and nothing once you were dead. Therefore, the only sensible course of action was to believe in God.

Blaise Pascal was a renowned French polymath of the 17th century, scientist, philosopher, mathematician, inventor, and later in life a theologian. Among his many contributions was an attempt to prove by logical means the existence of God, which came to be known as Pascal’s Wager. Stated simply, Pascal reasoned that not believing in God, if there was one, would damn you to eternal suffering. Conversely, believing in God, if there wasn’t one, would cost you little in this life and nothing once you were dead. Therefore, the only sensible course of action was to believe in God. “It feels qualitatively different this time.” There are few people I know in South Africa who don’t think this about the

“It feels qualitatively different this time.” There are few people I know in South Africa who don’t think this about the  How can data be biased? Isn’t it supposed to be an objective reflection of the real world? We all know that these are somewhat naive rhetorical questions, since data can easily inherit bias from the people who collect and analyze it, just as an algorithm can make biased suggestions if it’s trained on biased datasets. A better question is, how do biases creep in, and what can we do about them? Catherine D’Ignazio is an MIT professor who has studied how biases creep into our data and algorithms, and even into the expression of values that purport to protect objective analysis. We discuss examples of these processes and how to use data to make things better.

How can data be biased? Isn’t it supposed to be an objective reflection of the real world? We all know that these are somewhat naive rhetorical questions, since data can easily inherit bias from the people who collect and analyze it, just as an algorithm can make biased suggestions if it’s trained on biased datasets. A better question is, how do biases creep in, and what can we do about them? Catherine D’Ignazio is an MIT professor who has studied how biases creep into our data and algorithms, and even into the expression of values that purport to protect objective analysis. We discuss examples of these processes and how to use data to make things better. Human rights activists, journalists and lawyers across the world have been targeted by authoritarian governments using hacking software sold by the Israeli surveillance company NSO Group, according to an investigation into a massive data leak.

Human rights activists, journalists and lawyers across the world have been targeted by authoritarian governments using hacking software sold by the Israeli surveillance company NSO Group, according to an investigation into a massive data leak.