Category: Recommended Reading

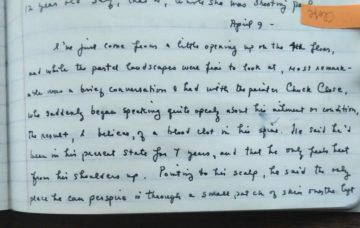

Notes on Chuck Close in Rome

Henri Cole at The Paris Review:

I’ve just come from a little opening up on the fourth floor, and while the pastel landscapes were fine to look at, most remarkable was a brief conversation I had with the painter Chuck Close, who suddenly began speaking quite openly about his ailment or condition, the result, I believe, of a blood clot in his spine. He said he’s been in his present state for seven years, and that he only feels heat from his shoulders up. Pointing to his scalp, he said the only place he can perspire is through a small patch of skin on the left side of his head. When he is touched anywhere below his shoulders, what he feels is an icy cold. He is happiest in the sun in his bathing suit.

I’ve just come from a little opening up on the fourth floor, and while the pastel landscapes were fine to look at, most remarkable was a brief conversation I had with the painter Chuck Close, who suddenly began speaking quite openly about his ailment or condition, the result, I believe, of a blood clot in his spine. He said he’s been in his present state for seven years, and that he only feels heat from his shoulders up. Pointing to his scalp, he said the only place he can perspire is through a small patch of skin on the left side of his head. When he is touched anywhere below his shoulders, what he feels is an icy cold. He is happiest in the sun in his bathing suit.

When he paints, he straps his brushes to his wrists. It is easier for him to paint than to draw, because he can paint with his arm out before him; to draw requires more mobility than he has. He talked with such candor that a small group of us was drawn to him.

more here.

Nine Nasty Words: English in the Gutter – Then, Now, and Forever

Fergus Butler-Gallie at Literary Review:

The lavatory facilities at Trisha’s bar, that glorious survivor of old Soho, adorned with photos of Al Capone and the pope, bear a legend written at eye level: ‘USE AS URINAL ONLY. NO SITTING.’ Except someone – I believe they are known usually as a ‘wag’ – has inserted an H into the final word, rendering it an equally familiar (and, arguably, more appropriate) piece of Anglo-Saxon. Or ought that to be Proto-Indo-European? As John McWhorter informs us in Nine Nasty Words, the history of that graffitied verb (though, as he points out, it can also be a noun, an adjective, a pronoun and even ‘with a bit of adjustment’ an adverb) goes back to the word skei – used by steppe dwellers of yore and meaning ‘to cut off’. It really is fascinating, the things one can learn in a lavatory.

The lavatory facilities at Trisha’s bar, that glorious survivor of old Soho, adorned with photos of Al Capone and the pope, bear a legend written at eye level: ‘USE AS URINAL ONLY. NO SITTING.’ Except someone – I believe they are known usually as a ‘wag’ – has inserted an H into the final word, rendering it an equally familiar (and, arguably, more appropriate) piece of Anglo-Saxon. Or ought that to be Proto-Indo-European? As John McWhorter informs us in Nine Nasty Words, the history of that graffitied verb (though, as he points out, it can also be a noun, an adjective, a pronoun and even ‘with a bit of adjustment’ an adverb) goes back to the word skei – used by steppe dwellers of yore and meaning ‘to cut off’. It really is fascinating, the things one can learn in a lavatory.

Skei’s modern-day descendant is one of nine words profiled by McWhorter in this spirited and scholarly history of profanities. As you’d expect in a work by a professor of linguistics, etymologies and tales of bastardisation form a sizeable proportion of each chapter.

more here.

Feminism for Women: The Real Route to Liberation

Rachel Cooke in The Guardian:

Away from the sulphurous world of Twitter, the feminist campaigner and journalist Julie Bindel is best known as the co-founder of Justice for Women, an organisation that since 1990 has advocated for those convicted of murder after having experienced violence by men; JfW campaigned successfully for the release of Emma Humphreys, who killed her violent pimp, Trevor Armitage, in 1985, and more recently for Sally Challen, who was convicted of the murder of her abusive husband, Richard, in 2010. Thanks to this work, and to her reporting elsewhere, Bindel also has expertise in the areas of porn, prostitution and sex trafficking; she was one of those who helped to break the story of the grooming gangs operating in the north of England, an investigation that would eventually lead to the independent inquiry into child sexual exploitation in Rotherham in 2013.

Away from the sulphurous world of Twitter, the feminist campaigner and journalist Julie Bindel is best known as the co-founder of Justice for Women, an organisation that since 1990 has advocated for those convicted of murder after having experienced violence by men; JfW campaigned successfully for the release of Emma Humphreys, who killed her violent pimp, Trevor Armitage, in 1985, and more recently for Sally Challen, who was convicted of the murder of her abusive husband, Richard, in 2010. Thanks to this work, and to her reporting elsewhere, Bindel also has expertise in the areas of porn, prostitution and sex trafficking; she was one of those who helped to break the story of the grooming gangs operating in the north of England, an investigation that would eventually lead to the independent inquiry into child sexual exploitation in Rotherham in 2013.

All of which surely makes her a Good Thing: a person of integrity, bravery and determination. But alas, as she writes in her new book, Feminism for Women, there are people for whom none of this is relevant. To them, Bindel is a Bad Thing, and they would like her to disappear – if not from the world, then at least from public life. In recent years, she has been de-platformed by numerous universities and other institutions following protests by assorted trans activists and their allies, among them those who argue that “sex work is work”. Even when such events do go ahead, there’s often trouble. At one, a man tried to punch her in the face. At another, a debate about pornography, her opponent, a man who has made money in that industry, was given a warm welcome by the students who’d tried so hard to get her taken off the bill. What, you might well wonder, has she done to invoke such anger, disapproval and bizarre contrarianism? Why does her past now count for so little? Is it really such a crime to believe, as she does, that sex is a material reality, and gender a social construct?

More here.

Schemer or Naïf? Elizabeth Holmes Is Going to Trial.

Griffith and Woo in The New York Times:

SAN FRANCISCO — After four years, repeated delays and the birth of her baby, Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of the blood testing start-up Theranos, is set to stand trial for fraud, capping a saga of Silicon Valley hubris, ambition and deception. Jury selection begins on Tuesday in federal court in San Jose, Calif., followed by opening arguments next week. Ms. Holmes, whose trial is expected to last three to four months, is battling 12 counts of fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud over false claims she made about Theranos’s blood tests and business. In 2018, the Department of Justice indicted both her and her business partner and onetime boyfriend, Ramesh Balwani, known as Sunny, with the charges. Mr. Balwani’s trial will begin early next year. Both have pleaded not guilty.

SAN FRANCISCO — After four years, repeated delays and the birth of her baby, Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of the blood testing start-up Theranos, is set to stand trial for fraud, capping a saga of Silicon Valley hubris, ambition and deception. Jury selection begins on Tuesday in federal court in San Jose, Calif., followed by opening arguments next week. Ms. Holmes, whose trial is expected to last three to four months, is battling 12 counts of fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud over false claims she made about Theranos’s blood tests and business. In 2018, the Department of Justice indicted both her and her business partner and onetime boyfriend, Ramesh Balwani, known as Sunny, with the charges. Mr. Balwani’s trial will begin early next year. Both have pleaded not guilty.

Ms. Holmes’s case has been held up as a parable of Silicon Valley’s swashbuckling “fake it till you make it” culture, which has helped propel the region’s start-ups to unfathomable riches and economic power. That same spirit has also allowed grifters and unethical hustlers to flourish, often with little consequence, raising questions about Silicon Valley’s tightening grip on society. But the trial will ultimately be about one individual. And the central question will be whether Ms. Holmes was a deceptive schemer driven by greed and power, or a naïf who believed her own lies and was manipulated by Mr. Balwani.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

A Scratch

what is god

and what is stone

the dividing line

if it exists

is very thin

at jejuri

and every other stone

is god or his cousin

there is no crop

other than god

and god is harvested here

around the year

and round the clock

out of the bad earth

and the hard rock

that giant hunk of rock

the size of a bedroom

is khandoba’s wife turned to stone

the crack that runs across

is the scar from the broadsword

he struck her down with

once in a fit of rage

scratch a rock

and a legend springs

by Arun Kolatkar

from Jejuri

New York Review Book, 1974

Link: Jejuri

Monday, August 30, 2021

Create an “Instant Community” with other visitors to 3QD

Dear Readers,

Dear Readers,

We are collaborating with the company Now4real to bring you a new feature: the ability to chat in real time with any other people who happen to be visiting 3QD at the same time. You will notice in the left lower corner of your screen a widget which looks like the image shown at the top right of this post. The large number in the center indicates the number of current visitors reading 3QD. The smaller number in the little circle indicates the number of unread messages currently posted and available to read by clicking the widget.

Once you post a message in the chat area, it is available for anyone to read and respond to for 3 hours, after which it will automatically be deleted. We are not completely sure whether this will prove to be a useful way for 3QD readers to communicate with each other but it is an interesting supplement to comments and we are going to try it out as an experiment for a couple of weeks. Please let us know in the comments area of this post if you find it useful and would like us to keep it permanently.

Here is some information about the company provided by Now4real:

With Now4real, we aim at introducing a new paradigm for the web. We call it “instant communities”. An instant community is the group of people who happen to be visiting the same web page at the same time. The moment an online article is being read by someone, it becomes like a virtual place because a human is dedicating time and attention to it. That person is at home, in the office, or on a train, but is also on the web page containing that article. It’s quite surprising that until now, there has been no means for people to meet in these virtual places. Now4real connects these people in real time, by detecting and showing how many readers are present “right now” and where they are from in the world, and by providing a live group chat dedicated to that website. Chat messages are ephemeral, to stimulate the continuous birth of new and extemporaneous instant communities.

Try it and see if you like it! NEW POSTS ARE BELOW.

Sunday, August 29, 2021

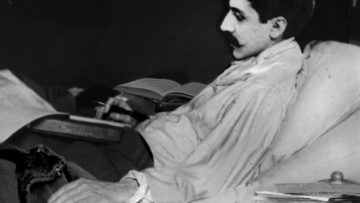

Proust’s Panmnemonicon

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Marcel Proust represents many things. Chief among these perhaps, especially for non-French readers, is quantity, and therefore the marathon-like endurance of anyone who actually reads all seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time, and can prove it. A 2016 cartoon in the New Yorker features a middle-aged couple sitting up in bed when one of them realises he and his partner are exactly the age at which they must start the opus if they hope to finish it before death. In a classic Looney Tunes episode Bugs Bunny has sent Elmer Fudd into a dustcloud of St. Vitus-like commotion from which he cannot escape; the sheer temporal extension of Fudd’s state is marked by Bugs sitting down next to him and patiently opening the cover of Remembrance of Things Past (as it used to be called in English).

Marcel Proust represents many things. Chief among these perhaps, especially for non-French readers, is quantity, and therefore the marathon-like endurance of anyone who actually reads all seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time, and can prove it. A 2016 cartoon in the New Yorker features a middle-aged couple sitting up in bed when one of them realises he and his partner are exactly the age at which they must start the opus if they hope to finish it before death. In a classic Looney Tunes episode Bugs Bunny has sent Elmer Fudd into a dustcloud of St. Vitus-like commotion from which he cannot escape; the sheer temporal extension of Fudd’s state is marked by Bugs sitting down next to him and patiently opening the cover of Remembrance of Things Past (as it used to be called in English).

Corollary to the length and weight of Proust’s work is the idea that to take it on amounts to a form of world-renunciation, and potentially an abnegation of our “real” moral connections and political duties. I recall shortly after September 11, 2001, Christopher Hitchens wrote that he had recently been on the cusp of giving up on politics altogether and devoting himself to a sustained critical work on the French novelist, only to be awoken and drawn back into the world by “Islamofascism”, and to the calling of militant atheism that would occupy him for the rest of his life.

More here.

Reimagining Humanity’s Obligation to Wild Animals

Rachel Nuwer in Undark:

I was once challenged by a friend to explain why it matters if species go extinct. Flustered, I launched into a rambling monologue about the intrinsic value of life and the importance of biodiversity for creating functioning ecosystems that ultimately prop up human economies. I don’t remember what my friend said; he certainly didn’t declare himself a born-again conservationist on the spot. But I do remember feeling frustrated that, in my inability to articulate a specific reason, I had somehow let down not only myself, but the entire planet.

I was once challenged by a friend to explain why it matters if species go extinct. Flustered, I launched into a rambling monologue about the intrinsic value of life and the importance of biodiversity for creating functioning ecosystems that ultimately prop up human economies. I don’t remember what my friend said; he certainly didn’t declare himself a born-again conservationist on the spot. But I do remember feeling frustrated that, in my inability to articulate a specific reason, I had somehow let down not only myself, but the entire planet.

The conversation would have gone very differently had I already read environmental journalist Emma Marris’s “Wild Souls: Freedom and Flourishing in the Non-Human World,” a razor-sharp exploration of the worth of wild animals and the species they belong to, and the responsibility we have toward them. “I wanted to know whether the massive human impact on Earth changes our obligation to animals,” Marris writes. “Our emotions about animals have always been strong, but are our intuitions about how — and whether — to interact with them still correct?”

More here.

Why America needs a Department of the Future

Kim Heacox in The Guardian:

Shortly before he died in 2007, the celebrated American novelist, iconoclast and second world war veteran Kurt Vonnegut gave a final interview. “My country is in ruins,” he said. “I’m a fish in a poisoned fishbowl.” Vonnegut was 84, and sounded razor sharp as he spoke about inequality and political shortsightedness, adding that in the history of the United States “one thing that no cabinet has ever had is a Secretary of the Future, and there are no plans at all for my children and grandchildren.”

Shortly before he died in 2007, the celebrated American novelist, iconoclast and second world war veteran Kurt Vonnegut gave a final interview. “My country is in ruins,” he said. “I’m a fish in a poisoned fishbowl.” Vonnegut was 84, and sounded razor sharp as he spoke about inequality and political shortsightedness, adding that in the history of the United States “one thing that no cabinet has ever had is a Secretary of the Future, and there are no plans at all for my children and grandchildren.”

“Why should I care about future generations?” asked the comedian Groucho Marx. “What have they ever done for me?”

More here.

Prison Tech Comes Home

Erin McElroy, Meredith Whittaker, and Nicole E. Weber in Public Books:

Throughout the pandemic, new surveillance systems—used by landlords, educational institutions, and employers—have converged, capturing new forms of data and exerting new forms of control in domestic spaces. COVID-19 prompted bosses and schools to accelerate the deployment of surveillance and tracking systems. As the pandemic drags on, many are still monitoring and assessing remote learners and workers in their most intimate environments. Landlords, meanwhile, took the pandemic as a time to promise “touchless” convenience and increased control over the homes of their tenants, rushing to install tracking systems in renters’ homes. Whatever the marketing promises, ultimately landlords’, bosses’, and schools’ intrusion of surveillance technologies into the home extends the carceral state into domestic spaces. In doing so, it also reveals the mutability of surveillance and assessment technologies, and the way the same systems can play many roles, while ultimately serving the powerful.

Throughout the pandemic, new surveillance systems—used by landlords, educational institutions, and employers—have converged, capturing new forms of data and exerting new forms of control in domestic spaces. COVID-19 prompted bosses and schools to accelerate the deployment of surveillance and tracking systems. As the pandemic drags on, many are still monitoring and assessing remote learners and workers in their most intimate environments. Landlords, meanwhile, took the pandemic as a time to promise “touchless” convenience and increased control over the homes of their tenants, rushing to install tracking systems in renters’ homes. Whatever the marketing promises, ultimately landlords’, bosses’, and schools’ intrusion of surveillance technologies into the home extends the carceral state into domestic spaces. In doing so, it also reveals the mutability of surveillance and assessment technologies, and the way the same systems can play many roles, while ultimately serving the powerful.

Abolitionist organizers and scholars have long demonstrated the ways in which the carceral state exists well beyond prisons, jails, and police. As Michelle Alexander reminds us in her foreword to the excellent book Prison by Any Other Name, “‘Mass incarceration’ should be understood to encompass all versions of racial and social control wherever they can be found, including prisons, jails, schools, forced ‘treatment’ centers, and immigrant detention centers, as well as homes and neighborhoods converted to digital prisons.”

More here.

The Standup Who Doubles as a Digital Emily Post

Andrew Marantz in The New Yorker:

On a recent afternoon, the comedian Jaboukie Young-White walked into Syndicated, a bar and movie theatre in Bushwick. He had bleach-blond hair and the beginnings of a mustache, and he wore workout clothes. “I like to exercise, but ‘I want to look plump and juicy’ isn’t enough motivation,” he said. “I need more of a narrative.” He had reserved a spot in a Muay Thai class nearby, but the class had been cancelled because of a sudden rainstorm. The gym’s owner texted him a video, and Young-White held up his phone: floor mats covered in gushing water. “Life during climate change, I guess,” he said, sliding into a booth. Two movie projectors beamed images onto a wall—“Fitzcarraldo,” the Werner Herzog film, next to “Whenever, Wherever,” the Shakira video. “Every bar should have this,” Young-White said. “If you’re on a first date and things get super awkward, you can at least look up and comment on something together, instead of each disappearing into your phones.”

On a recent afternoon, the comedian Jaboukie Young-White walked into Syndicated, a bar and movie theatre in Bushwick. He had bleach-blond hair and the beginnings of a mustache, and he wore workout clothes. “I like to exercise, but ‘I want to look plump and juicy’ isn’t enough motivation,” he said. “I need more of a narrative.” He had reserved a spot in a Muay Thai class nearby, but the class had been cancelled because of a sudden rainstorm. The gym’s owner texted him a video, and Young-White held up his phone: floor mats covered in gushing water. “Life during climate change, I guess,” he said, sliding into a booth. Two movie projectors beamed images onto a wall—“Fitzcarraldo,” the Werner Herzog film, next to “Whenever, Wherever,” the Shakira video. “Every bar should have this,” Young-White said. “If you’re on a first date and things get super awkward, you can at least look up and comment on something together, instead of each disappearing into your phones.”

Young-White has thought a lot about cell phones, dating, and New York, in part because he stars in a movie called “Dating & New York,” out this month, a traditional rom-com refreshed for the swipe-right era. The writer and director, Jonah Feingold, was born in the nineties, as were most of the cast members, including Young-White, who is twenty-seven. “The Internet matured as we were maturing,” he said. “We did a lot of comparing notes, on set, about the little etiquettes and mores that you naturally learn when your whole life is mediated through a phone. The right way to punctuate a text, things like that.” Once, as a New Year’s resolution, Young-White turned on read receipts, which notify the people you’re texting with when you’ve seen their messages. “The idea was, this will make me more accountable, so I won’t keep forgetting to respond,” he said. Instead, he forgot that the setting was on: when he let a conversation lag, it seemed like a snub. He said, “It was actually Bo”—the comedian Bo Burnham, another connoisseur of the ways in which the Internet is warping human relationships—“who told me my read receipts were on. He went, ‘I assumed it was a power move.’ ”

More here.

Afghanistan Redux: Malala Yousafzai, White Feminism and Saving Afghan Women

Fawzia Afzal-Khan in Counterpunch:

The case at hand that prevents me from an unqualified rooting for the category of “experience,” is the exemplary case of Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan, who has traversed the distance from female “experience” to feminist “expertise”, and who, like others before (and since) that have made that journey from the “margins” to the “center” of imperial power, has now switched from being a “voice of the oppressed” to becoming an “expert” who can speak to us and teach us about those authentic “other” women in the global south—in this case, Afghan women– to whom her prior proximity (“experience”)– renders her an “expert” on today. From experience to expertise then, is a pretty straightforward line, following the predictable path forged also by white feminism in thrall and service to imperial designs past and present. This is the path that was announced with great fanfare shortly after 9/11 by First Lady Laura Bush and enthusiastically supported by the Feminist Majority Foundation, that would “save brown women from brown men” by going in to the “backward” country of Afghanistan overrun by crazy “Moslem” men, in the process unleashing a 20-year war on the population that had had nothing to do with 9/11. The initial military intervention was then followed up over the next two decades with countless “development” schemes that enriched a few at the expense of the many, and when the cost of this unending war became unpopular with the citizenry “back home” in the USA over time—we left the hapless “natives” that included those very women we had been so concerned with “saving,” at the mercy of anarchy and chaos.

The case at hand that prevents me from an unqualified rooting for the category of “experience,” is the exemplary case of Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan, who has traversed the distance from female “experience” to feminist “expertise”, and who, like others before (and since) that have made that journey from the “margins” to the “center” of imperial power, has now switched from being a “voice of the oppressed” to becoming an “expert” who can speak to us and teach us about those authentic “other” women in the global south—in this case, Afghan women– to whom her prior proximity (“experience”)– renders her an “expert” on today. From experience to expertise then, is a pretty straightforward line, following the predictable path forged also by white feminism in thrall and service to imperial designs past and present. This is the path that was announced with great fanfare shortly after 9/11 by First Lady Laura Bush and enthusiastically supported by the Feminist Majority Foundation, that would “save brown women from brown men” by going in to the “backward” country of Afghanistan overrun by crazy “Moslem” men, in the process unleashing a 20-year war on the population that had had nothing to do with 9/11. The initial military intervention was then followed up over the next two decades with countless “development” schemes that enriched a few at the expense of the many, and when the cost of this unending war became unpopular with the citizenry “back home” in the USA over time—we left the hapless “natives” that included those very women we had been so concerned with “saving,” at the mercy of anarchy and chaos.

It is against this backdrop of “expertise” (represented back then by policy feminists such as those at the helm of the Feminist Majority Foundation who supported the war in Afghanistan ostensibly to “save” those poor brown Muslim women from the Taliban)–that the “voice” of Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan who was shot at by the Pakistani branch of the Taliban for wanting to attend school—needs to be understood and assessed when she speaks today in the aftermath of that war. Obviously, the spill-over effects of the 20-year war into neighboring Pakistan negatively affected Malala herself (she almost died because of the Taliban attack upon her), but those same circumstances also helped her ascend to worldwide fame, leading her to being read/seen as the “voice of experience” (by western feminists and policy makers), whose “voice” could then be mobilized in service of several of the goals of the continuing War on Terror.

More here.

Jean Breeze (1956- 2021) dub poet

Larry Harlow (1939 – 2021) salsa musician

Charlie Watts (1941 – 2021) drummer

Sunday Poem

An Old Woman

An old woman grabs

hold of your sleeve

and tags along.

She wants a fifty paise coin.

She says she will take you

to the horseshoe shrine.

You’ve seen it already.

She hobbles along anyway

and tightens her grip on your shirt.

She won’t let you go.

You know how old women are.

They stick to you like a burr.

You turn around and face her

with an air of finality.

You want to end the farce.

When you hear her say,

“What else can an old woman do

on hills as wretched as these?”

You look right at the sky.

Clear through the bullet holes

she has for her eyes.

And as you look on

the cracks that begin around her eyes

spread beyond her skin.

And the hills crack.

And the temples crack.

And the sky falls.

with a plateglass clatter

around the shatter proof crone

who stands alone.

And you are reduced

to so much small change

in her hand.

by Arun Kolatkar

from Jejuri

Publisher: New York Review of Books

Originally published in Opinion Literary Quarterly, 1974

Saturday, August 28, 2021

Legitimacy Gap

Aditi Sahasrabuddhe in Phenomenal World (Photo by Ibrahim Boran on Unsplash):

Aditi Sahasrabuddhe in Phenomenal World (Photo by Ibrahim Boran on Unsplash):

We live in the age of the central bank. The financial crisis of 2008 and the COVID-19 crash of 2020 have made visible the central role of the US Federal Reserve and its overseas counterparts in the international financial system. The tasks of central banks are dramatic—rescuing banks and preventing financial collapse—and have earned them applause for avoiding a second and third Great Depression, and have brought relief to the economy. But these actions bore a distributional impact. Most of the financial policies adopted in response to the crisis—quantitative easing, bond purchases, and low interest rates—have protected wealth without creating new opportunities for those who don’t possess it. As the “K-shaped” charts of the 2020 recovery made plain, a market rebound did not spell economic well-being for ordinary people.

The outsize role of central banks—especially the Fed—in the international financial system has led to some skepticism about central banks and their independence. Central bank independence (CBI) grants the Fed immunity from public accountability and political interference. The Fed’s position as an independent authority in an internationally integrated market has allowed it to play, outside national borders, lender of last resort: extending liquidity assistance to foreign central banks through currency swap lines without requiring Congressional approval. Since the 1970s, CBI has been justified using the language of credible commitment and the assumed apolitical nature of monetary policy. Protection from public pressure is thought to allow central bankers to act in accordance with the principles of economics to make policies which are “confidently expected to work.”

More here.

DeLongTODAY: China III: China Policy

The Costs of Climate Tipping Points Add Up

Gernot Wagner in Bloomberg (Photo by Melissa Bradley on Unsplash):

Gernot Wagner in Bloomberg (Photo by Melissa Bradley on Unsplash):

Tell me if you’ve heard this one before: Climate change isn’t about what we know, it’s about what we don’t. What we know is bad enough, what we don’t is potentially much worse. Consider, also, the irreversible, large-scale events — tipping points, like the Amazon drying out, the West-Antarctic or the Greenland ice sheet disintegrating — and the costs start to add up.

It’s precisely these costs of major planetary tipping points that I set out to calculate with three stellar colleagues in a paper published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy. The main finding, heavily caveated as is the wont of any such research: A conservative estimate raises the urgency of action today by around 25%. The metric to capture this urgency is the social cost of carbon, what each ton of CO₂ emitted today costs society — and, thus, should cost those doing the polluting.

That 25% alone represents a significant impact, but we cannot leave things there. For one, it represents what we call a “probable underestimate,” for all sorts of important reasons, not least the fact that both the science and perhaps especially the economics are indeed inherently conservative.

More here.