Paul Coates at The Current:

Andrzej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds (1958) has rightly been lauded as one of the finest of postwar East-Central European films, and the most vital work of the Polish School, the group of filmmakers who, starting in the midfifties, cast startlingly truthful images of the recent war and its aftermath, putting Polish cinema on the world map. It is salutary, however, to remember how much controversy has dogged the film within Poland itself, and that it is more than a matter of regime-led misgivings about a work with potentially subversive accents. It stems from the film’s pursuit of conflicting goals: to deal with the Polish Home Army’s resistance against the incoming, Soviet-backed Communist regime and yet satisfy both the Polish populace who held that army dear and a Communist Party that wielded powers of censorship, even though it had renounced a Stalinist rigor of repression. Criticize the Home Army too strongly and the audience will turn on you; offend the regime and your film might be amputated or aborted. (Wajda himself reported efforts to remove the protagonist’s death scene going right down to the wire of the first screening.)

Andrzej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds (1958) has rightly been lauded as one of the finest of postwar East-Central European films, and the most vital work of the Polish School, the group of filmmakers who, starting in the midfifties, cast startlingly truthful images of the recent war and its aftermath, putting Polish cinema on the world map. It is salutary, however, to remember how much controversy has dogged the film within Poland itself, and that it is more than a matter of regime-led misgivings about a work with potentially subversive accents. It stems from the film’s pursuit of conflicting goals: to deal with the Polish Home Army’s resistance against the incoming, Soviet-backed Communist regime and yet satisfy both the Polish populace who held that army dear and a Communist Party that wielded powers of censorship, even though it had renounced a Stalinist rigor of repression. Criticize the Home Army too strongly and the audience will turn on you; offend the regime and your film might be amputated or aborted. (Wajda himself reported efforts to remove the protagonist’s death scene going right down to the wire of the first screening.)

more here.

Polachek’s career started with guys and guitars. She co-founded the indie band Chairlift when she was in college, in the early two-thousands, and the group quickly reached a steady level of afternoon-set-at-a-festival success. But “Pang,” a sumptuous avant-pop record about the ecstatic terrors of love, had inspired a fervent new following. Instead of being the lead singer of a band, Polachek was now an alt-pop diva whose fans wrote things like “omfg i’m gonna cry and pee yes queen” on Instagram and showed up to gigs in leather and mesh. (The phrase “bunny is a rider” was printed on white cotton thongs; they sold out in every size.) Polachek, who has also written songs for other performers—including “No Angel,” a track on Beyoncé’s self-titled album, from 2013—is as stylized as a Top Forty artist, but she has an experimental aesthetic, tending toward the esoteric. The visuals for “Pang” were partly inspired by the mid-twentieth-century American illustrator Eyvind Earle and the seventeenth-century engraver Jacques Hurtu. She has co-directed several of her frequently surreal music videos with her boyfriend, the visual artist Matt Copson.

Polachek’s career started with guys and guitars. She co-founded the indie band Chairlift when she was in college, in the early two-thousands, and the group quickly reached a steady level of afternoon-set-at-a-festival success. But “Pang,” a sumptuous avant-pop record about the ecstatic terrors of love, had inspired a fervent new following. Instead of being the lead singer of a band, Polachek was now an alt-pop diva whose fans wrote things like “omfg i’m gonna cry and pee yes queen” on Instagram and showed up to gigs in leather and mesh. (The phrase “bunny is a rider” was printed on white cotton thongs; they sold out in every size.) Polachek, who has also written songs for other performers—including “No Angel,” a track on Beyoncé’s self-titled album, from 2013—is as stylized as a Top Forty artist, but she has an experimental aesthetic, tending toward the esoteric. The visuals for “Pang” were partly inspired by the mid-twentieth-century American illustrator Eyvind Earle and the seventeenth-century engraver Jacques Hurtu. She has co-directed several of her frequently surreal music videos with her boyfriend, the visual artist Matt Copson. Covid has caused a deep crisis in the already suffering developing world, which contains nearly half of all humanity. And this will have serious implications for the future of the world economy and political order. Initially, Covid was something of a rich country’s disease. It started in industrial China and spread to places like the United States, Italy and the United Kingdom. But now none of the wealthiest countries falls within the top 10 worst-hit countries in terms of Covid deaths per capita. In the US, Covid has gone from the leading cause of death to seventh place in just over a year.

Covid has caused a deep crisis in the already suffering developing world, which contains nearly half of all humanity. And this will have serious implications for the future of the world economy and political order. Initially, Covid was something of a rich country’s disease. It started in industrial China and spread to places like the United States, Italy and the United Kingdom. But now none of the wealthiest countries falls within the top 10 worst-hit countries in terms of Covid deaths per capita. In the US, Covid has gone from the leading cause of death to seventh place in just over a year. Research articles in the life sciences are more ambitious than ever. The amount of data in high-impact journals has doubled over 20 years

Research articles in the life sciences are more ambitious than ever. The amount of data in high-impact journals has doubled over 20 years September 14, 2021, marked the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, the Florentine author of the world’s most renowned and masterful of all poems, The Divine Comedy. Not only did this poem have a marked impact on European vernacular languages in its notable departure from Latin, it also transformed how we understand the relationships among perpetrators, victims, and witnesses of violence. But more than this: it is perhaps with Dante that we really began to imagine what Hell looked like, which in turn demanded a revolution in how we understood the wretchedness of life, the fate of the sinful, and the path out through an all too earthly call to love and poetry.

September 14, 2021, marked the 700th anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri, the Florentine author of the world’s most renowned and masterful of all poems, The Divine Comedy. Not only did this poem have a marked impact on European vernacular languages in its notable departure from Latin, it also transformed how we understand the relationships among perpetrators, victims, and witnesses of violence. But more than this: it is perhaps with Dante that we really began to imagine what Hell looked like, which in turn demanded a revolution in how we understood the wretchedness of life, the fate of the sinful, and the path out through an all too earthly call to love and poetry. How human beings behave is, for fairly evident reasons, a topic of intense interest to human beings. And yet, not only is there much we don’t understand about human behavior, different academic disciplines seem to have developed completely incompatible models to try to explain it. And as today’s guest Herb Gintis complains, they don’t put nearly enough effort into talking to each other to try to reconcile their views. So that what he’s here to do. Using game theory and a model of rational behavior — with an expanded notion of “rationality” that includes social as well as personally selfish interests — he thinks that we can come to an understanding that includes ideas from biology, economics, psychology, and sociology, to more accurately account for how people actually behave.

How human beings behave is, for fairly evident reasons, a topic of intense interest to human beings. And yet, not only is there much we don’t understand about human behavior, different academic disciplines seem to have developed completely incompatible models to try to explain it. And as today’s guest Herb Gintis complains, they don’t put nearly enough effort into talking to each other to try to reconcile their views. So that what he’s here to do. Using game theory and a model of rational behavior — with an expanded notion of “rationality” that includes social as well as personally selfish interests — he thinks that we can come to an understanding that includes ideas from biology, economics, psychology, and sociology, to more accurately account for how people actually behave. Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) was the foremost anthropologist of the twentieth century, and one of its most renowned intellectuals of any persuasion. Common readers, if they know him at all, tend to do so only by Tristes Tropiques (French for “Sad Tropics”), his 1955 memoir of his fieldwork among Brazilian tribes and his travels as an academic junketeer in other alien enclaves. That book is salted with animadversions on the spread of the “monoculture” of the West doing its worst to refashion the world in its unhandsome image.

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908–2009) was the foremost anthropologist of the twentieth century, and one of its most renowned intellectuals of any persuasion. Common readers, if they know him at all, tend to do so only by Tristes Tropiques (French for “Sad Tropics”), his 1955 memoir of his fieldwork among Brazilian tribes and his travels as an academic junketeer in other alien enclaves. That book is salted with animadversions on the spread of the “monoculture” of the West doing its worst to refashion the world in its unhandsome image. The day I was diagnosed with cancer—serious cancer, out-of-the-blue cancer—I reeled out of the doctor’s office and onto the familiar street. My children’s dentist was on that block, and the Rite Aid where we got cheap toys after their checkups. Just an hour and a half earlier, I’d walked down that street and my world had been safe and whole—my two little boys, my good husband, my career as a writer just beginning to unfold. My life! I hadn’t even known to give it a backward glance.

The day I was diagnosed with cancer—serious cancer, out-of-the-blue cancer—I reeled out of the doctor’s office and onto the familiar street. My children’s dentist was on that block, and the Rite Aid where we got cheap toys after their checkups. Just an hour and a half earlier, I’d walked down that street and my world had been safe and whole—my two little boys, my good husband, my career as a writer just beginning to unfold. My life! I hadn’t even known to give it a backward glance. In 1789, newly elected president

In 1789, newly elected president  “Climate change may be too wild a stream to be navigated in the accustomed barques of narration, yet we have entered a time in human history when the wild has become the norm,” writes Amitav Ghosh in his book The Great Derangement, and part of the reason Anna and I chose more lyric modes of documentation for this project was the impossibility of a linear narrative, of straightforward representation. How could we present something that’s long-term and large-scale dramatic, but harder to see in smaller daily moments, and almost impossible to photograph: raised roads in Miami Beach leaving sidewalks and storefronts below grade, or giant pumps that move water from the streets back into the Bay that simply look like large metal boxes? What language should we use to describe the paradox of a city in a time of sea-level rise, lying just feet above sea level, that’s also built on porous limestone—where rampant development means that multimillion-dollar waterfront houses and condominiums are still going up all along the shoreline?

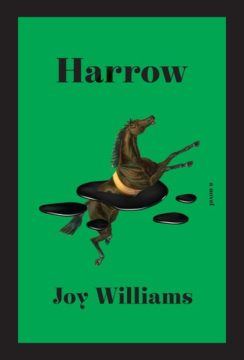

“Climate change may be too wild a stream to be navigated in the accustomed barques of narration, yet we have entered a time in human history when the wild has become the norm,” writes Amitav Ghosh in his book The Great Derangement, and part of the reason Anna and I chose more lyric modes of documentation for this project was the impossibility of a linear narrative, of straightforward representation. How could we present something that’s long-term and large-scale dramatic, but harder to see in smaller daily moments, and almost impossible to photograph: raised roads in Miami Beach leaving sidewalks and storefronts below grade, or giant pumps that move water from the streets back into the Bay that simply look like large metal boxes? What language should we use to describe the paradox of a city in a time of sea-level rise, lying just feet above sea level, that’s also built on porous limestone—where rampant development means that multimillion-dollar waterfront houses and condominiums are still going up all along the shoreline? That something can be existent without properly existing, caught halfway between being and nonbeing, or between life and death, is a concept much larger than Williams’s straightforward claims about the eradication of the Everglades. The notion of a foundational in-between-ness, of existence itself as a fleeting or fugacious form, has been central to her work from the very beginning. The writer Vincent Scarpa, who has studied and taught Williams’s work extensively, put it to me this way: “That liminal state between being alive and being dead—that’s Joy’s playground.” He reminded me that nursing homes, “these collectives where it goes unacknowledged or otherwise refused that the living are only playing at living,” feature frequently in her work. “But we’re really all in that liminal state, just to varying degrees.” Sure enough, a nursing home is a central setting of Williams’s novel The Quick and the Dead (2000), which also features a petulant ghost. Expand the category a bit and you’ll find hospitals and hotels along with rest homes. Her 1988 novel, Breaking and Entering, is about a pair of drifters who squat Florida vacation homes. Florida itself is sometimes known as “God’s Waiting Room.”

That something can be existent without properly existing, caught halfway between being and nonbeing, or between life and death, is a concept much larger than Williams’s straightforward claims about the eradication of the Everglades. The notion of a foundational in-between-ness, of existence itself as a fleeting or fugacious form, has been central to her work from the very beginning. The writer Vincent Scarpa, who has studied and taught Williams’s work extensively, put it to me this way: “That liminal state between being alive and being dead—that’s Joy’s playground.” He reminded me that nursing homes, “these collectives where it goes unacknowledged or otherwise refused that the living are only playing at living,” feature frequently in her work. “But we’re really all in that liminal state, just to varying degrees.” Sure enough, a nursing home is a central setting of Williams’s novel The Quick and the Dead (2000), which also features a petulant ghost. Expand the category a bit and you’ll find hospitals and hotels along with rest homes. Her 1988 novel, Breaking and Entering, is about a pair of drifters who squat Florida vacation homes. Florida itself is sometimes known as “God’s Waiting Room.” Half a decade on, “Brexit and Trump” remain shorthand for the rise of right-wing populism and a profound unsettling of liberal democracies. One curious fact is rarely mentioned: the campaigns of Hillary Clinton and Remain in 2016 had similar-sounding slogans, which spectacularly failed to resonate with large parts of the electorate: “Stronger Together” and “Stronger in Europe”. Evidently, a significant number of citizens felt that they might actually be stronger, or in some other sense better off, by separating. What does that tell us about the fault lines of politics today?

Half a decade on, “Brexit and Trump” remain shorthand for the rise of right-wing populism and a profound unsettling of liberal democracies. One curious fact is rarely mentioned: the campaigns of Hillary Clinton and Remain in 2016 had similar-sounding slogans, which spectacularly failed to resonate with large parts of the electorate: “Stronger Together” and “Stronger in Europe”. Evidently, a significant number of citizens felt that they might actually be stronger, or in some other sense better off, by separating. What does that tell us about the fault lines of politics today? Our mushy brains seem a far cry from the solid silicon chips in computer processors, but scientists have a long history of comparing the two. As Alan Turing

Our mushy brains seem a far cry from the solid silicon chips in computer processors, but scientists have a long history of comparing the two. As Alan Turing  A little over half a century ago, in 1970, my mother’s parents took her to Kabul to shop for her wedding. From Lahore, Kabul was only a short flight or a long drive away, much closer than Karachi. It was the first time my mother had left Pakistan.

A little over half a century ago, in 1970, my mother’s parents took her to Kabul to shop for her wedding. From Lahore, Kabul was only a short flight or a long drive away, much closer than Karachi. It was the first time my mother had left Pakistan.