E. Farrell Helbling in Nature:

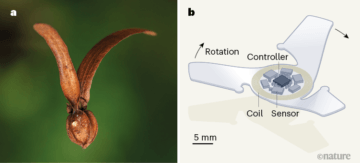

In a paper in Nature, Kim et al.1 report 3D fliers that are inspired by the passive, helicopter-style wind-dispersal mechanism of certain seeds. The adopted production processes enable the rapid parallel fabrication of many fliers and permit the integration of simple electronic circuits using standard silicon-on-insulator techniques. Tuning the design parameters — such as the diameter, porosity and wing type — generates beneficial interactions between the devices and the surrounding air. Such interactions lower the terminal velocity of the fliers, increase air resistance and improve stability by inducing rotational motion. When combined with complex integrated circuits, these devices could form dynamic sensor networks for environmental monitoring, wireless communication nodes or various other technologies based on the network of Internet-connected devices called the Internet of Things.

In a paper in Nature, Kim et al.1 report 3D fliers that are inspired by the passive, helicopter-style wind-dispersal mechanism of certain seeds. The adopted production processes enable the rapid parallel fabrication of many fliers and permit the integration of simple electronic circuits using standard silicon-on-insulator techniques. Tuning the design parameters — such as the diameter, porosity and wing type — generates beneficial interactions between the devices and the surrounding air. Such interactions lower the terminal velocity of the fliers, increase air resistance and improve stability by inducing rotational motion. When combined with complex integrated circuits, these devices could form dynamic sensor networks for environmental monitoring, wireless communication nodes or various other technologies based on the network of Internet-connected devices called the Internet of Things.

So far, research into collectives of aerial vehicles has been focused on active systems, including quadcopters2,3 and insect- or bird-inspired robotic platforms4. Active systems have the benefit of being able to move independently through their environment. However, their practical applications are limited because of the size and safety concerns of larger platforms (such as quadcopters, which have a wingspan of about 50 centimetres) and lack of onboard electronics and power supplies that enable autonomous locomotion in real-world settings in the case of smaller platforms (with a wingspan of roughly 3.5 cm)5. Furthermore, because these research platforms5–7 are highly specialized and assembled by hand, they cannot be used for studies of collective systems.

More here.

On December 15, 1929, Dr. Philip M. Lovell, the imperiously eccentric health columnist for the Los Angeles Times, invited readers to tour his ultramodern new home, at 4616 Dundee Drive, in the hills of Los Feliz. On a page crowded with ads promoting quack cures for “chronic constipation” and “sagging flabby chins,” Lovell announced three days of open houses, adding that “Mr. Richard T. Neutra, architect who designed and supervised the construction . . . will conduct the audience from room to room.” Neutra’s middle initial was actually J., but this recent Austrian immigrant, thirty-seven years old and underemployed, had little reason to complain: he was being launched as a pioneer of American modernist architecture. Thousands of people took the tour; striking photographs were published. Three years later, Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the codifiers of the International Style,

On December 15, 1929, Dr. Philip M. Lovell, the imperiously eccentric health columnist for the Los Angeles Times, invited readers to tour his ultramodern new home, at 4616 Dundee Drive, in the hills of Los Feliz. On a page crowded with ads promoting quack cures for “chronic constipation” and “sagging flabby chins,” Lovell announced three days of open houses, adding that “Mr. Richard T. Neutra, architect who designed and supervised the construction . . . will conduct the audience from room to room.” Neutra’s middle initial was actually J., but this recent Austrian immigrant, thirty-seven years old and underemployed, had little reason to complain: he was being launched as a pioneer of American modernist architecture. Thousands of people took the tour; striking photographs were published. Three years later, Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock, the codifiers of the International Style,  THE ARC THAT SAID HIMSELF

THE ARC THAT SAID HIMSELF We will be switching over to new servers today, Thursday, September 23, and this means we may not be able to post new items for a day or possibly longer. Thanks for your patience, and we’ll make the interruption as short as possible.

We will be switching over to new servers today, Thursday, September 23, and this means we may not be able to post new items for a day or possibly longer. Thanks for your patience, and we’ll make the interruption as short as possible. He died the day after Christmas. His loved ones washed and anointed his body and kept vigil at his bedside. “He looked like a king,” Jenifer told me. “He was really, really beautiful.” She showed me a few photos. His body had been laid atop a hemp shroud and covered from the neck down in a layer of dried herbs and flower petals. Bouquets of lavender and tree fronds wreathed his head, and a ladybug pendant on a beaded string lay across his brow like a diadem. Only his bearded face was exposed, wearing the peaceful, inscrutable expression of the dead. He did look like a king, or like a woodland deity out of Celtic mythology—his gauze-wrapped neck the only evidence of his life as a mortal.

He died the day after Christmas. His loved ones washed and anointed his body and kept vigil at his bedside. “He looked like a king,” Jenifer told me. “He was really, really beautiful.” She showed me a few photos. His body had been laid atop a hemp shroud and covered from the neck down in a layer of dried herbs and flower petals. Bouquets of lavender and tree fronds wreathed his head, and a ladybug pendant on a beaded string lay across his brow like a diadem. Only his bearded face was exposed, wearing the peaceful, inscrutable expression of the dead. He did look like a king, or like a woodland deity out of Celtic mythology—his gauze-wrapped neck the only evidence of his life as a mortal. The one thing you can say for sure about Katie Kitamura’s wonderfully sly new novel – the follow-up to her 2017 breakthrough A Separation, and one of Barack Obama’s summer reading picks – is that it offers a portrait of limbo. The unnamed narrator, a Japanese woman raised in Europe, has accepted a one-year contract as an interpreter at the International Criminal Court – identified only as “the Court” – in The Hague. The book’s title – which, like that of its predecessor, rejects the firmness of the definite article – refers to the relationship one might ideally have with language, spaces, customs, other people, one’s own emotions, the past. It’s unclear, at least at first, to what degree the character’s own failure to achieve this state herself is a product of temperament or circumstances – whether she is simply adjusting, or whether this is how she always presents, and negotiates, the world.

The one thing you can say for sure about Katie Kitamura’s wonderfully sly new novel – the follow-up to her 2017 breakthrough A Separation, and one of Barack Obama’s summer reading picks – is that it offers a portrait of limbo. The unnamed narrator, a Japanese woman raised in Europe, has accepted a one-year contract as an interpreter at the International Criminal Court – identified only as “the Court” – in The Hague. The book’s title – which, like that of its predecessor, rejects the firmness of the definite article – refers to the relationship one might ideally have with language, spaces, customs, other people, one’s own emotions, the past. It’s unclear, at least at first, to what degree the character’s own failure to achieve this state herself is a product of temperament or circumstances – whether she is simply adjusting, or whether this is how she always presents, and negotiates, the world. The historian Joe Moran begins his 2018 style guide, First You Write a Sentence, by outlining a comic routine unfortunately familiar to many of us:

The historian Joe Moran begins his 2018 style guide, First You Write a Sentence, by outlining a comic routine unfortunately familiar to many of us: Back in 2000, when

Back in 2000, when  I travelled to New York City in August for the first time since the pandemic began, to visit friends who had just bought their first home. They are firmly upper-middle class and in their 40s. They took out a mortgage for $1.5m (£1.1m) to buy a place in a Brooklyn neighbourhood that was regarded until recently as an area immune to gentrification. So far, so typical. Asset ownership comes late these days.

I travelled to New York City in August for the first time since the pandemic began, to visit friends who had just bought their first home. They are firmly upper-middle class and in their 40s. They took out a mortgage for $1.5m (£1.1m) to buy a place in a Brooklyn neighbourhood that was regarded until recently as an area immune to gentrification. So far, so typical. Asset ownership comes late these days. Rich in meaning and metaphor, the word ‘heart’ conjures up many images: a pump, courage, kindness, love, a suit in a deck of cards, a shape or the most important part of an object or matter. These days, it also brings to mind the global increase in heart attacks and cardiovascular damage that attends COVID-19. As a subject for a book, the heart is an organ with a lot going for it.

Rich in meaning and metaphor, the word ‘heart’ conjures up many images: a pump, courage, kindness, love, a suit in a deck of cards, a shape or the most important part of an object or matter. These days, it also brings to mind the global increase in heart attacks and cardiovascular damage that attends COVID-19. As a subject for a book, the heart is an organ with a lot going for it. What is found in a good conversation? It is certainly correct to say words—the more engagingly put, the better. But conversation also includes “eyes, smiles, the silences between the words,” as the Swedish author Annika Thor wrote. It is when those elements hum along together that we feel most deeply engaged with, and most connected to, our conversational partner, as if we are in sync with them. Like good conversationalists, neuroscientists at Dartmouth College have taken that idea and carried it to new places. As part of a series of studies on how two minds meet in real life, they reported surprising findings on the interplay of eye contact and the synchronization of neural activity between two people during conversation. In a paper published on September 14 in Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences USA, the researchers suggest that being in tune with a conversational partner is good but that

What is found in a good conversation? It is certainly correct to say words—the more engagingly put, the better. But conversation also includes “eyes, smiles, the silences between the words,” as the Swedish author Annika Thor wrote. It is when those elements hum along together that we feel most deeply engaged with, and most connected to, our conversational partner, as if we are in sync with them. Like good conversationalists, neuroscientists at Dartmouth College have taken that idea and carried it to new places. As part of a series of studies on how two minds meet in real life, they reported surprising findings on the interplay of eye contact and the synchronization of neural activity between two people during conversation. In a paper published on September 14 in Proceedings of the Natural Academy of Sciences USA, the researchers suggest that being in tune with a conversational partner is good but that  On a December morning in 1947 when three fellows at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study set out for the Third Circuit Court in Trenton, it was decided that the job of making sure that the brilliant but naively innocent logician Kurt Gödel didn’t say something intemperate at his citizenship hearing would fall to Albert Einstein. Economist Oscar Morgenstern would drive, Einstein rode shotgun, and a nervous Gödel sat in the back. With squibs of low winter light, both wave and particle, dappled across the rattling windows of Morgenstern’s car, Einstein turned back and asked, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” There had been no doubt that the philosopher had adequately studied, but as to whether it was proper to be fully honest was another issue. Less than two centuries before, and the signatories of the U.S. Constitution had supposedly crafted a document defined by separation of powers and coequal government, checks and balances, action and reaction. “The science of politics,” wrote Alexander Hamilton in “Federalist Paper No. 9,” “has received great improvement,” though as Gödel discovered, clearly not perfection. With a completism that only a Teutonic logician was capable of, Gödel had carefully read the foundational documents of American political theory, he’d poured over the Federalist Papers and the Constitution, and he’d made an alarming discovery.

On a December morning in 1947 when three fellows at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study set out for the Third Circuit Court in Trenton, it was decided that the job of making sure that the brilliant but naively innocent logician Kurt Gödel didn’t say something intemperate at his citizenship hearing would fall to Albert Einstein. Economist Oscar Morgenstern would drive, Einstein rode shotgun, and a nervous Gödel sat in the back. With squibs of low winter light, both wave and particle, dappled across the rattling windows of Morgenstern’s car, Einstein turned back and asked, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” There had been no doubt that the philosopher had adequately studied, but as to whether it was proper to be fully honest was another issue. Less than two centuries before, and the signatories of the U.S. Constitution had supposedly crafted a document defined by separation of powers and coequal government, checks and balances, action and reaction. “The science of politics,” wrote Alexander Hamilton in “Federalist Paper No. 9,” “has received great improvement,” though as Gödel discovered, clearly not perfection. With a completism that only a Teutonic logician was capable of, Gödel had carefully read the foundational documents of American political theory, he’d poured over the Federalist Papers and the Constitution, and he’d made an alarming discovery. Testosterone’s wide-reaching effects occur not just in the human body, but across society, powering acts of aggression, violence, and the large disparity in their commission between men and women, according to Harvard human evolutionary biologist

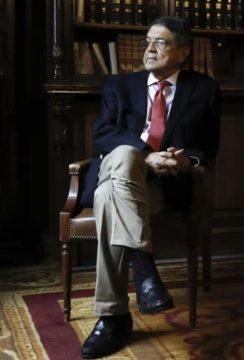

Testosterone’s wide-reaching effects occur not just in the human body, but across society, powering acts of aggression, violence, and the large disparity in their commission between men and women, according to Harvard human evolutionary biologist  Sergio Ramírez, Nicaragua’s best-known living writer, hero of the Sandinista revolution, and former vice-president of the volcanic Central American nation, has lived through both tougher times and duller publicity tours.

Sergio Ramírez, Nicaragua’s best-known living writer, hero of the Sandinista revolution, and former vice-president of the volcanic Central American nation, has lived through both tougher times and duller publicity tours.