Daniel Levin Becker in Literary Hub:

Are there unrappable words? Not words that can’t be gerrymandered into rhyme by tricks of truncation or pronunciation, but words so ungainly, so unwieldy, so unhip, so unhip-hop, as to definitively resist rap’s tractor-beam powers of assimilation. Do such words exist? No! says the wide-eyed idealist in me. I mean, probably, says the grizzled skeptic, who doubts I’ll hear pulchritude or amortize or hoarfrost or chilblains dropped over a beat before I die.

Are there unrappable words? Not words that can’t be gerrymandered into rhyme by tricks of truncation or pronunciation, but words so ungainly, so unwieldy, so unhip, so unhip-hop, as to definitively resist rap’s tractor-beam powers of assimilation. Do such words exist? No! says the wide-eyed idealist in me. I mean, probably, says the grizzled skeptic, who doubts I’ll hear pulchritude or amortize or hoarfrost or chilblains dropped over a beat before I die.

But then there was a time not so long ago when I would have put lugubrious on that list, and now here we are. Lil Ugly Mane, a producer from Virginia with a gothically bug-eyed rapping style and at least a dozen different stage names, rhymes it with a run of propositions like flyer than a stewardess and been sick since the uterus, so I’m certainly not complaining.

More here.

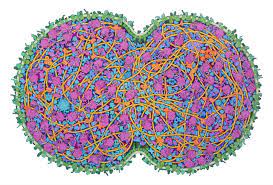

Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall.

Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took much of the world by surprise. It is an unprovoked and unjustified attack that will go down in history as one of the major war crimes of the 21st century, argues Noam Chomsky in the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows. Political considerations, such as those cited by Russian President Vladimir Putin, cannot be used as arguments to justify the launching of an invasion against a sovereign nation. In the face of this horrific invasion, though, the U.S. must choose urgent diplomacy over military escalation, as the latter could constitute a “death warrant for the species, with no victors,” Chomsky says.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took much of the world by surprise. It is an unprovoked and unjustified attack that will go down in history as one of the major war crimes of the 21st century, argues Noam Chomsky in the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows. Political considerations, such as those cited by Russian President Vladimir Putin, cannot be used as arguments to justify the launching of an invasion against a sovereign nation. In the face of this horrific invasion, though, the U.S. must choose urgent diplomacy over military escalation, as the latter could constitute a “death warrant for the species, with no victors,” Chomsky says. P

P It was by accident that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch cloth merchant, first saw a living cell. He’d begun making magnifying lenses at home, perhaps to better judge the quality of his cloth. One day, out of curiosity, he held one up to a drop of lake water. He saw that the drop was teeming with numberless tiny animals. These animalcules, as he called them, were everywhere he looked—in the stuff between his teeth, in soil, in food gone bad. A decade earlier, in 1665, an Englishman named Robert Hooke had examined cork through a lens; he’d found structures that he called “cells,” and the name had stuck. Van Leeuwenhoek seemed to see an even more striking view: his cells moved with apparent purpose. No one believed him when he told people what he’d discovered, and he had to ask local bigwigs—the town priest, a notary, a lawyer—to peer through his lenses and attest to what they saw.

It was by accident that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch cloth merchant, first saw a living cell. He’d begun making magnifying lenses at home, perhaps to better judge the quality of his cloth. One day, out of curiosity, he held one up to a drop of lake water. He saw that the drop was teeming with numberless tiny animals. These animalcules, as he called them, were everywhere he looked—in the stuff between his teeth, in soil, in food gone bad. A decade earlier, in 1665, an Englishman named Robert Hooke had examined cork through a lens; he’d found structures that he called “cells,” and the name had stuck. Van Leeuwenhoek seemed to see an even more striking view: his cells moved with apparent purpose. No one believed him when he told people what he’d discovered, and he had to ask local bigwigs—the town priest, a notary, a lawyer—to peer through his lenses and attest to what they saw. No clear genetic origin has been found for stuttering, and neither have emotional origins like trauma been ruled out. Still there is no cure. Some techniques work for some stutterers, some of the time. A hundred years ago doctors tried cutting out portions of the tongues of stutterers, killing and maiming many, curing none. Online, there are testimonies from people who swear by certain techniques, people who are taking Vitamin B1, people who are gloriously fluent, and people in the midst of a tough recurrence.

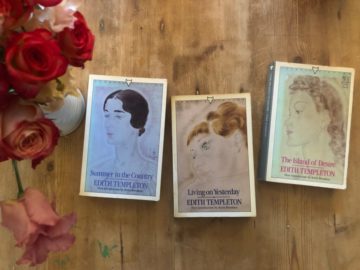

No clear genetic origin has been found for stuttering, and neither have emotional origins like trauma been ruled out. Still there is no cure. Some techniques work for some stutterers, some of the time. A hundred years ago doctors tried cutting out portions of the tongues of stutterers, killing and maiming many, curing none. Online, there are testimonies from people who swear by certain techniques, people who are taking Vitamin B1, people who are gloriously fluent, and people in the midst of a tough recurrence. Such sexually explicit content became what Templeton was best known for during her lifetime—a reputation made yet more notorious due to the fact that she drew direct inspiration from her own illicit trysts. She was born into a wealthy upper-class family in Prague in 1916, and raised in a world of sophistication, civility, and gentility: this social milieu would have been shocked by such self-exposing erotica. Edith Passerová, as she was then, met her first husband, the Englishman William Stockwell Templeton, when she was only seventeen. They married five years later, in 1938, and lived in England. The union quickly disintegrated, but rather than return home to what by that point was a war-torn Europe, Templeton remained in Britain after their separation. She initially took a job with the American War Office, during which time she had the brief fling described in “The Darts of Cupid.” The story’s candid, violently charged eroticism caused a stir when it was first published in The New Yorker, but even its level of graphic sexual detail paled in comparison to that of Templeton’s most famous novel.

Such sexually explicit content became what Templeton was best known for during her lifetime—a reputation made yet more notorious due to the fact that she drew direct inspiration from her own illicit trysts. She was born into a wealthy upper-class family in Prague in 1916, and raised in a world of sophistication, civility, and gentility: this social milieu would have been shocked by such self-exposing erotica. Edith Passerová, as she was then, met her first husband, the Englishman William Stockwell Templeton, when she was only seventeen. They married five years later, in 1938, and lived in England. The union quickly disintegrated, but rather than return home to what by that point was a war-torn Europe, Templeton remained in Britain after their separation. She initially took a job with the American War Office, during which time she had the brief fling described in “The Darts of Cupid.” The story’s candid, violently charged eroticism caused a stir when it was first published in The New Yorker, but even its level of graphic sexual detail paled in comparison to that of Templeton’s most famous novel. A week ago I unrestrainedly used the phrase Слава Україні!/Glory to Ukraine!, and a few friends and readers were surprised to see me resorting to jingoism, even if for a country not my own. This struck some as particularly inadvisable, since the phrase is associated in some of its expressions with far-right Ukrainian nationalism, and with the handful of people in Ukraine who minimally justify Putin’s claim to be undertaking a campaign of “de-Nazification” there. The first time I used the phrase was in 2014, at a rally in Paris in support of the Maidan demonstrators in Kyiv, among a Ukrainian diaspora that was resolutely pro-democracy and worlds away from any far-right sentiments. But a rally is one thing, an essay another, and as the week wore on I admit my use of the phrase echoed in my mind, and came to feel increasingly like a mistake.

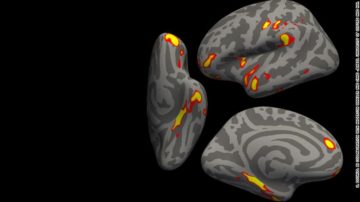

A week ago I unrestrainedly used the phrase Слава Україні!/Glory to Ukraine!, and a few friends and readers were surprised to see me resorting to jingoism, even if for a country not my own. This struck some as particularly inadvisable, since the phrase is associated in some of its expressions with far-right Ukrainian nationalism, and with the handful of people in Ukraine who minimally justify Putin’s claim to be undertaking a campaign of “de-Nazification” there. The first time I used the phrase was in 2014, at a rally in Paris in support of the Maidan demonstrators in Kyiv, among a Ukrainian diaspora that was resolutely pro-democracy and worlds away from any far-right sentiments. But a rally is one thing, an essay another, and as the week wore on I admit my use of the phrase echoed in my mind, and came to feel increasingly like a mistake. People who have even a mild case of Covid-19 may have accelerated aging of the brain and other changes to it, according to a new study.

People who have even a mild case of Covid-19 may have accelerated aging of the brain and other changes to it, according to a new study. Morgan Meis (MM): Jed, your new book, Authority and Freedom*, has come out in the last few weeks. Congratulations! In it, right near the end, you give this lovely quote from WH Auden, from his poem about Yeats:

Morgan Meis (MM): Jed, your new book, Authority and Freedom*, has come out in the last few weeks. Congratulations! In it, right near the end, you give this lovely quote from WH Auden, from his poem about Yeats: Thursday morning, after the publication of

Thursday morning, after the publication of  The mission to turn space into the next frontier for express deliveries took off from a modest propeller plane above a remote airstrip in the shadow of the Santa Ana mountains. Shortly after sunrise on a recent Saturday, an engineer for Inversion Space, a start-up that’s barely a year old, tossed a capsule resembling a flying saucer out the open door of an aircraft flying at 3,000 feet. The capsule, 20 inches in diameter, somersaulted in the air for a few seconds before a parachute deployed and snapped the container upright for a slow descent. “It was slow to open,” said Justin Fiaschetti, Inversion’s 23-year-old chief executive, who anxiously watched the parachute through the viewfinder of a camera with a long lens.

The mission to turn space into the next frontier for express deliveries took off from a modest propeller plane above a remote airstrip in the shadow of the Santa Ana mountains. Shortly after sunrise on a recent Saturday, an engineer for Inversion Space, a start-up that’s barely a year old, tossed a capsule resembling a flying saucer out the open door of an aircraft flying at 3,000 feet. The capsule, 20 inches in diameter, somersaulted in the air for a few seconds before a parachute deployed and snapped the container upright for a slow descent. “It was slow to open,” said Justin Fiaschetti, Inversion’s 23-year-old chief executive, who anxiously watched the parachute through the viewfinder of a camera with a long lens. The heliostats will reflect the sun’s rays onto a tall, mirror-covered tower to be set in the center of town. In turn, the tower will deflect the light onto other mirrors mounted on building facades, diffusing the beams to prevent dangerously focused, scorching rays. The mirrors will not drench the town in an even, blinding glare; this is no movie set where, with the flip of a switch and a dozen flood bulbs, night dazzlingly becomes day. (Such broad, total illumination would require impossibly enormous mirrors.) Instead, light will cascade down to create areas of illumination, or “hotspots.” Preliminary sketches reveal a pleasantly dappled effect, not unlike the sun-speckled lanes of Thomas Kinkade paintings. These bright spots, however, will be about “lawn size,” large enough for people to cluster inside, like fish schooling in shimmering pools of sunshine.

The heliostats will reflect the sun’s rays onto a tall, mirror-covered tower to be set in the center of town. In turn, the tower will deflect the light onto other mirrors mounted on building facades, diffusing the beams to prevent dangerously focused, scorching rays. The mirrors will not drench the town in an even, blinding glare; this is no movie set where, with the flip of a switch and a dozen flood bulbs, night dazzlingly becomes day. (Such broad, total illumination would require impossibly enormous mirrors.) Instead, light will cascade down to create areas of illumination, or “hotspots.” Preliminary sketches reveal a pleasantly dappled effect, not unlike the sun-speckled lanes of Thomas Kinkade paintings. These bright spots, however, will be about “lawn size,” large enough for people to cluster inside, like fish schooling in shimmering pools of sunshine. The word “salon,” for a starry convocation of creative types, intelligentsia, and patrons, has never firmly penetrated English. It retains a pair of transatlantic wet feet from the phenomenon’s storied annals, chiefly in France, since the eighteenth century. So it was that the all-time most glamorous and consequential American instance, thriving in New York between 1915 and 1920, centered on Europeans in temporary flight from the miseries of the First World War. Their hosts were Walter Arensberg, a Pittsburgh steel heir, and his wife, Louise Stevens, an even wealthier Massachusetts textile-industry legatee. The couple had been thunderstruck by the 1913 Armory Show of international contemporary art, which exposed Americans to Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and, in particular, Marcel Duchamp. Made the previous year, his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” a cunning mashup of Cubism and Futurism, with its title hand-lettered along the bottom, was the event’s prime sensation: at once insinuating indecency and making it hard to perceive, what with the image’s scalloped planes, which a Times critic jovially likened to “an explosion in a shingle factory.”

The word “salon,” for a starry convocation of creative types, intelligentsia, and patrons, has never firmly penetrated English. It retains a pair of transatlantic wet feet from the phenomenon’s storied annals, chiefly in France, since the eighteenth century. So it was that the all-time most glamorous and consequential American instance, thriving in New York between 1915 and 1920, centered on Europeans in temporary flight from the miseries of the First World War. Their hosts were Walter Arensberg, a Pittsburgh steel heir, and his wife, Louise Stevens, an even wealthier Massachusetts textile-industry legatee. The couple had been thunderstruck by the 1913 Armory Show of international contemporary art, which exposed Americans to Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and, in particular, Marcel Duchamp. Made the previous year, his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” a cunning mashup of Cubism and Futurism, with its title hand-lettered along the bottom, was the event’s prime sensation: at once insinuating indecency and making it hard to perceive, what with the image’s scalloped planes, which a Times critic jovially likened to “an explosion in a shingle factory.”