(GDP)— It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. – Robert Kennedy, 3.18.1968

Gross Domestic Product

Surely it is sick with all its counting. Sick, too,

of selling the numbers which mean nothing

until they do. It counts the distance from the top

of the flagpole to the middle and how long it takes

to raise our symbols up. It counts wild blazes

in Western states. It counts the placed, the displaced,

the length of a grey blanket raining ash in its wake.

It counts the monuments but has forgotten the graves.

The most hateful among us, the poisoned water supply,

the garbage island measured by its relative size to a state—

who could stand to know so much as the brain we create?

Who else could count the gold in the bank or how little

trickles out to towns that need it most? Our gracious host

assures us they have counted every vote and the winner

will be announced after a short commercial break.

Also—the chef would like to know how you liked your steak.

If you got sick put your name on the list and we will call

your name shortly. Please hold. Your patience has been noted

and scored on a scale from complacent to irate. You didn’t win,

but then again, most people don’t and we’ve got the numbers

to prove it. Move along, nothing to see here says he

who needs to believe he saw nothing, would omit

all wonder from the official record. Nay, it won’t

count those who found a wolf’s teeth flashing

at the edge of the woods and the field of lavender

behind it all, odorous and possible. It can’t count

the nautilus hearts beating for what ought to have happened,

who imagine pressing on through the heat and the smog to

a more perfect future, that tense in which to read the new world.

by Bobby Bolt

from The Echotheo Review

One of the recent trends on TikTok is an aesthetic called “night luxe.” It embodies the kind of performative opulence one usually encounters at New Year’s Eve parties: champagne, disco balls, bedazzled accessories, and golden sparkles. “Night luxe” doesn’t actually mean anything. It isn’t a

One of the recent trends on TikTok is an aesthetic called “night luxe.” It embodies the kind of performative opulence one usually encounters at New Year’s Eve parties: champagne, disco balls, bedazzled accessories, and golden sparkles. “Night luxe” doesn’t actually mean anything. It isn’t a  In the early years of the 1980s, I was fooling around with a novel that explored a future in which the United States had become disunited. Part of it had turned into a theocratic dictatorship based on 17th-century New England Puritan religious tenets and jurisprudence. I set this novel in and around Harvard University—an institution that in the 1980s was renowned for its liberalism, but that had begun three centuries earlier chiefly as a training college for Puritan clergy.

In the early years of the 1980s, I was fooling around with a novel that explored a future in which the United States had become disunited. Part of it had turned into a theocratic dictatorship based on 17th-century New England Puritan religious tenets and jurisprudence. I set this novel in and around Harvard University—an institution that in the 1980s was renowned for its liberalism, but that had begun three centuries earlier chiefly as a training college for Puritan clergy.

While living in an internment camp in Vichy France, Alexander Grothendieck was tutored in mathematics by another prisoner, a girl named Maria. Maria taught Grothendieck, who was twelve, the definition of a circle: all the points that are equidistant from a given point. The definition impressed him with “its simplicity and clarity,” he wrote years later. The property of perfect rotundity had until then appeared to him to be “mysterious beyond words.”

While living in an internment camp in Vichy France, Alexander Grothendieck was tutored in mathematics by another prisoner, a girl named Maria. Maria taught Grothendieck, who was twelve, the definition of a circle: all the points that are equidistant from a given point. The definition impressed him with “its simplicity and clarity,” he wrote years later. The property of perfect rotundity had until then appeared to him to be “mysterious beyond words.” Though the 1973 decision in Roe established a constitutionally protected right to abortion, it never guaranteed abortion access. The Supreme Court held only that state criminal laws banning abortion were an infringement of the constitutional right to privacy. Patients, in consultation with their physicians, could elect to have an abortion for any reason during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester states could regulate abortions in order to protect the pregnant person’s health or the dignity of potential life, but after the second trimester, a state was permitted to ban abortion unless terminating the pregnancy was necessary to preserve the patient’s life or health. This trimester system was abandoned in 1992, when the Court held that states could restrict abortion before viability—around twenty-four weeks of gestation—so long as the regulation did not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” The Court’s decision to reject Roe’s trimester framework nevertheless claimed to preserve “the essential holding of Roe.”

Though the 1973 decision in Roe established a constitutionally protected right to abortion, it never guaranteed abortion access. The Supreme Court held only that state criminal laws banning abortion were an infringement of the constitutional right to privacy. Patients, in consultation with their physicians, could elect to have an abortion for any reason during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester states could regulate abortions in order to protect the pregnant person’s health or the dignity of potential life, but after the second trimester, a state was permitted to ban abortion unless terminating the pregnancy was necessary to preserve the patient’s life or health. This trimester system was abandoned in 1992, when the Court held that states could restrict abortion before viability—around twenty-four weeks of gestation—so long as the regulation did not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” The Court’s decision to reject Roe’s trimester framework nevertheless claimed to preserve “the essential holding of Roe.” I am a university professor. I make my living teaching and doing research at a liberal arts school in Southern California. Last year, I took a brave step: I decided to become a student and signed up for online Arabic classes. I joined an online language course offered by a company based in Cairo. Full disclosure: This was my third attempt at learning Arabic over the past 10 years. Arabic is a notoriously hard language, given its expansive vocabulary. A Moroccan feminist scholar told me once that there are 50 words for “love” in Arabic – a fascinating and intimidating fact. My earlier attempts at mastering synonyms had proved her right.

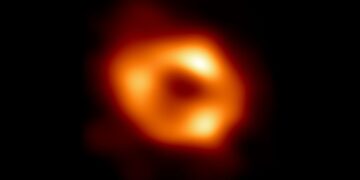

I am a university professor. I make my living teaching and doing research at a liberal arts school in Southern California. Last year, I took a brave step: I decided to become a student and signed up for online Arabic classes. I joined an online language course offered by a company based in Cairo. Full disclosure: This was my third attempt at learning Arabic over the past 10 years. Arabic is a notoriously hard language, given its expansive vocabulary. A Moroccan feminist scholar told me once that there are 50 words for “love” in Arabic – a fascinating and intimidating fact. My earlier attempts at mastering synonyms had proved her right. The mystery at the heart of the Milky Way has finally been solved. This morning, at simultaneous press conferences around the world, the astronomers of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) revealed the first image of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. It’s not the first picture of a black hole this collaboration has given us—that was

The mystery at the heart of the Milky Way has finally been solved. This morning, at simultaneous press conferences around the world, the astronomers of the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) revealed the first image of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. It’s not the first picture of a black hole this collaboration has given us—that was  The genre is as old, almost, as the modern novel, and shares its subversive nature. If Don Quixote, among many other things, brought fiction down from the chivalric heights to the pedestrian grounds, so literary biography served as a tonic to the genre of biography as a whole, which has always tended toward the exemplary. James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, considered by many to be the first modern literary biography, details its subject’s appetite for drink, his shabby clothes, his disgusting eating habits. Johnson himself thought it the “business of the biographer to…lead the thoughts into domestic privacies, and display the minute details of daily life.”

The genre is as old, almost, as the modern novel, and shares its subversive nature. If Don Quixote, among many other things, brought fiction down from the chivalric heights to the pedestrian grounds, so literary biography served as a tonic to the genre of biography as a whole, which has always tended toward the exemplary. James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson, considered by many to be the first modern literary biography, details its subject’s appetite for drink, his shabby clothes, his disgusting eating habits. Johnson himself thought it the “business of the biographer to…lead the thoughts into domestic privacies, and display the minute details of daily life.” If, in 1979, Rosalind Krauss famously said, “we find it indescribably embarrassing to mention art and spirit in the same sentence,” today many of us find it indescribably embarrassing not to.

If, in 1979, Rosalind Krauss famously said, “we find it indescribably embarrassing to mention art and spirit in the same sentence,” today many of us find it indescribably embarrassing not to. What explains the dramatic progress from 20th-century to 21st-century AI, and how can the remaining limitations of current AI be overcome? The widely accepted narrative attributes this progress to massive increases in the quantity of computational and data resources available to support statistical learning in deep artificial neural networks. We show that an additional crucial factor is the development of a new type of computation. Neurocompositional computing (Smolensky et al., 2022) adopts two principles that must be simultaneously respected to enable human-level cognition: the principles of Compositionality and Continuity. These have seemed irreconcilable until the recent mathematical discovery that compositionality can be realized not only through discrete methods of symbolic computing, but also through novel forms of continuous neural computing. The revolutionary recent progress in AI has resulted from the use of limited forms of neurocompositional computing. New, deeper forms of neurocompositional computing create AI systems that are more robust, accurate,

What explains the dramatic progress from 20th-century to 21st-century AI, and how can the remaining limitations of current AI be overcome? The widely accepted narrative attributes this progress to massive increases in the quantity of computational and data resources available to support statistical learning in deep artificial neural networks. We show that an additional crucial factor is the development of a new type of computation. Neurocompositional computing (Smolensky et al., 2022) adopts two principles that must be simultaneously respected to enable human-level cognition: the principles of Compositionality and Continuity. These have seemed irreconcilable until the recent mathematical discovery that compositionality can be realized not only through discrete methods of symbolic computing, but also through novel forms of continuous neural computing. The revolutionary recent progress in AI has resulted from the use of limited forms of neurocompositional computing. New, deeper forms of neurocompositional computing create AI systems that are more robust, accurate, To say that event A causes event B is to not only make a claim about our actual world, but about other possible worlds — in worlds where A didn’t happen but everything else was the same, B would not have happened. This leads to an obvious difficulty if we want to infer causes from sets of data — we generally only have data about the actual world. Happily, there are ways around this difficulty, and the study of causal relations is of central importance in modern social science and artificial intelligence research. Judea Pearl has been the leader of the “causal revolution,” and we talk about what that means and what questions remain unanswered.

To say that event A causes event B is to not only make a claim about our actual world, but about other possible worlds — in worlds where A didn’t happen but everything else was the same, B would not have happened. This leads to an obvious difficulty if we want to infer causes from sets of data — we generally only have data about the actual world. Happily, there are ways around this difficulty, and the study of causal relations is of central importance in modern social science and artificial intelligence research. Judea Pearl has been the leader of the “causal revolution,” and we talk about what that means and what questions remain unanswered. The departure of Sri Lanka’s prime minister,

The departure of Sri Lanka’s prime minister,  The more affecting terrors in Ghosts include domestic violence, lonely marriages, undignified old age, and suppressed identity. There are disastrous marriages galore: The titular housekeeper of “Mr. Jones” turns out to be the malevolent, long-dead servant who once helped an 18th-century nobleman isolate his deaf and mute wife there. In “The Lady’s Maid’s Bell,” servants come and go; the only constant is the abuse and neglect of the invalid lady of the house by her alcoholic and philandering husband. In “Kerfol,” it turns out that the “most romantic house in Brittany” is haunted not by the sadistic 17th-century aristocrat who owned it but by all the dogs he killed there, pets that had briefly enlivened his wife’s “desolate” and “extremely lonely” life. That backstory is related through the records of a long-ago court case, which diffuses the real-time suspense but does not dull the horrors of that cruel marriage.

The more affecting terrors in Ghosts include domestic violence, lonely marriages, undignified old age, and suppressed identity. There are disastrous marriages galore: The titular housekeeper of “Mr. Jones” turns out to be the malevolent, long-dead servant who once helped an 18th-century nobleman isolate his deaf and mute wife there. In “The Lady’s Maid’s Bell,” servants come and go; the only constant is the abuse and neglect of the invalid lady of the house by her alcoholic and philandering husband. In “Kerfol,” it turns out that the “most romantic house in Brittany” is haunted not by the sadistic 17th-century aristocrat who owned it but by all the dogs he killed there, pets that had briefly enlivened his wife’s “desolate” and “extremely lonely” life. That backstory is related through the records of a long-ago court case, which diffuses the real-time suspense but does not dull the horrors of that cruel marriage.