Adam Kovac in Daily Beast:

When drafting legislation, vocabulary counts for everything. Opposing viewpoints were passionately aired over seemingly minute details. Within this group, there were two sides: One believes that death is best described as permanent, and the other believes death is irreversible. The distinction is subtle, but critical. Fans of the latter definition argue that describing death as “permanent” doesn’t go far enough—death is only permanent if no medical action is taken, but irreversible means that nothing can be done. A North Dakota doctor by the name of Christopher DeCock, who opted for the bridge of the original Starship Enterprise as his background, used another fantasy tale to make his fandom of Team Irreversible known. “This isn’t Princess Bride, where you’re mostly dead,” he says, paraphrasing Billy Crystal’s comedic relief healer Miracle Max from the 1987 classic. “Either you’re dead or you’re not dead.”

When drafting legislation, vocabulary counts for everything. Opposing viewpoints were passionately aired over seemingly minute details. Within this group, there were two sides: One believes that death is best described as permanent, and the other believes death is irreversible. The distinction is subtle, but critical. Fans of the latter definition argue that describing death as “permanent” doesn’t go far enough—death is only permanent if no medical action is taken, but irreversible means that nothing can be done. A North Dakota doctor by the name of Christopher DeCock, who opted for the bridge of the original Starship Enterprise as his background, used another fantasy tale to make his fandom of Team Irreversible known. “This isn’t Princess Bride, where you’re mostly dead,” he says, paraphrasing Billy Crystal’s comedic relief healer Miracle Max from the 1987 classic. “Either you’re dead or you’re not dead.”

The debate over when death begins goes back more than half a century. Prior to that, death was rather straightforward: Life ended when the heart and lungs ceased to function. But in 1959, two French physicians, Pierre Mollaret and Maurice Goulon, documented for the first time a phenomenon they observed in two dozen patients who were connected to ventilators.

More here.

It may be time

It may be time Leonard Benardo in Dissent:

Leonard Benardo in Dissent: Raymond Geuss in The New Statesman:

Raymond Geuss in The New Statesman: Jewellord T. Nem Singh in Phenomenal World:

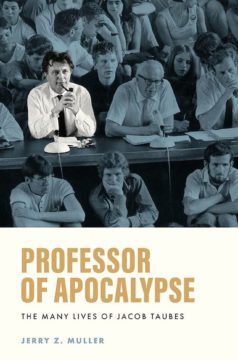

Jewellord T. Nem Singh in Phenomenal World: MANY READERS OF LARB and other literary journals may very well never even have heard the name — let alone be aware of the thought and personality — of the idiosyncratic philosopher and religious thinker Jacob Taubes (1923–1987). Why, then, would the distinguished intellectual historian Jerry Z. Muller dedicate many years to writing a highly detailed, nuanced biography of this apparently obscure figure? It would be sufficient to show that, in the second half of the 20th century, Taubes was an immensely well-connected and putatively brilliant man, an exotic, animating presence in the Western intellectual firmament, restlessly traversing Europe, the United States, and Israel. But what gives this study its special flavor is the fascinating, quasi-erotic, well-nigh demonic nature of the man’s personality and Muller’s tantalizing connection of these features to Taubes’s philosophical ruminations and religious and historical pursuits. Given his intensity and radicalism, his wildly vacillating moods and relationships, his unending contempt for cozy and settled bourgeois liberalism, and his search for some kind of messianic universal future, the title Muller has chosen for his biography, Professor of Apocalypse: The Many Lives of Jacob Taubes, could not be more apt.

MANY READERS OF LARB and other literary journals may very well never even have heard the name — let alone be aware of the thought and personality — of the idiosyncratic philosopher and religious thinker Jacob Taubes (1923–1987). Why, then, would the distinguished intellectual historian Jerry Z. Muller dedicate many years to writing a highly detailed, nuanced biography of this apparently obscure figure? It would be sufficient to show that, in the second half of the 20th century, Taubes was an immensely well-connected and putatively brilliant man, an exotic, animating presence in the Western intellectual firmament, restlessly traversing Europe, the United States, and Israel. But what gives this study its special flavor is the fascinating, quasi-erotic, well-nigh demonic nature of the man’s personality and Muller’s tantalizing connection of these features to Taubes’s philosophical ruminations and religious and historical pursuits. Given his intensity and radicalism, his wildly vacillating moods and relationships, his unending contempt for cozy and settled bourgeois liberalism, and his search for some kind of messianic universal future, the title Muller has chosen for his biography, Professor of Apocalypse: The Many Lives of Jacob Taubes, could not be more apt. What linked these loosely connected scholars, the book suggests, was their interest in using the study of exotic cultures to illuminate the peculiarities of the “civilised” world. As Malinowski put it, “in grasping the essential outlook of others, with reverence and real understanding, due even to savages, we cannot help widening our own”.

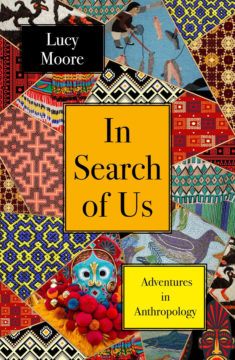

What linked these loosely connected scholars, the book suggests, was their interest in using the study of exotic cultures to illuminate the peculiarities of the “civilised” world. As Malinowski put it, “in grasping the essential outlook of others, with reverence and real understanding, due even to savages, we cannot help widening our own”.  THE SUMMERS ARE ALWAYS HOT

THE SUMMERS ARE ALWAYS HOT Though the 1973 decision in Roe established a constitutionally protected right to abortion, it never guaranteed abortion access. The Supreme Court held only that state criminal laws banning abortion were an infringement of the constitutional right to privacy. Patients, in consultation with their physicians, could elect to have an abortion for any reason during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester states could regulate abortions in order to protect the pregnant person’s health or the dignity of potential life, but after the second trimester, a state was permitted to ban abortion unless terminating the pregnancy was necessary to preserve the patient’s life or health. This trimester system was abandoned in 1992, when the Court held that states could restrict abortion before viability—around twenty-four weeks of gestation—so long as the regulation did not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” The Court’s decision to reject Roe’s trimester framework nevertheless claimed to preserve “the essential holding of Roe.”

Though the 1973 decision in Roe established a constitutionally protected right to abortion, it never guaranteed abortion access. The Supreme Court held only that state criminal laws banning abortion were an infringement of the constitutional right to privacy. Patients, in consultation with their physicians, could elect to have an abortion for any reason during the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester states could regulate abortions in order to protect the pregnant person’s health or the dignity of potential life, but after the second trimester, a state was permitted to ban abortion unless terminating the pregnancy was necessary to preserve the patient’s life or health. This trimester system was abandoned in 1992, when the Court held that states could restrict abortion before viability—around twenty-four weeks of gestation—so long as the regulation did not place a “substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion of a nonviable fetus.” The Court’s decision to reject Roe’s trimester framework nevertheless claimed to preserve “the essential holding of Roe.” Philosophers have seldom lived up to the ideal of radical doubt that they often claim as the prime directive of their tradition. They insist on questioning everything, while nonetheless holding onto many pieties. Foremost among these, perhaps, is the commandment handed down from the Oracle at Delphi and characterised by Plato as a life-motto of his master Socrates: “Know thyself.”

Philosophers have seldom lived up to the ideal of radical doubt that they often claim as the prime directive of their tradition. They insist on questioning everything, while nonetheless holding onto many pieties. Foremost among these, perhaps, is the commandment handed down from the Oracle at Delphi and characterised by Plato as a life-motto of his master Socrates: “Know thyself.” Ten years ago this week, Jennifer Doudna and her colleagues

Ten years ago this week, Jennifer Doudna and her colleagues  “Birmingham will not tolerate the disrespect of our Prophet… You will have repercussions for your actions.” So

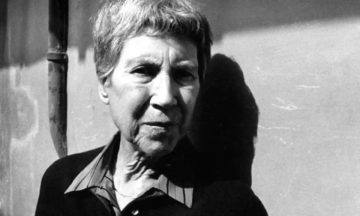

“Birmingham will not tolerate the disrespect of our Prophet… You will have repercussions for your actions.” So  When I first read Natalia Ginzburg’s work several years ago, I felt as if I was reading something that had been written for me, something that had been written almost inside my own head or heart. I was astonished that I had never encountered Ginzburg’s work before: that no one, knowing me, had ever told me about her books. It was as if her writing was a very important secret that I had been waiting all my life to discover. Far more than anything I myself had ever written or even tried to write, her words seemed to express something completely true about my experience of living, and about life itself. This kind of transformative encounter with a book is, for me, very rare, a moment of contact with what seems to be the essence of human existence. For this reason, I wanted to write a little about Natalia Ginzburg and her novel All Our Yesterdays. I would like to address myself in particular to other readers who are right now awaiting, whether they know it or not, their first and special meeting with her work.

When I first read Natalia Ginzburg’s work several years ago, I felt as if I was reading something that had been written for me, something that had been written almost inside my own head or heart. I was astonished that I had never encountered Ginzburg’s work before: that no one, knowing me, had ever told me about her books. It was as if her writing was a very important secret that I had been waiting all my life to discover. Far more than anything I myself had ever written or even tried to write, her words seemed to express something completely true about my experience of living, and about life itself. This kind of transformative encounter with a book is, for me, very rare, a moment of contact with what seems to be the essence of human existence. For this reason, I wanted to write a little about Natalia Ginzburg and her novel All Our Yesterdays. I would like to address myself in particular to other readers who are right now awaiting, whether they know it or not, their first and special meeting with her work. The viruses that cause the tropical diseases Zika and dengue fever can hijack the body odour of their hosts to their advantage, a study shows

The viruses that cause the tropical diseases Zika and dengue fever can hijack the body odour of their hosts to their advantage, a study shows