Colin Powers in Phenomenal World:

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman first announced Saudi Vision 2030 (SV2030), an economic diversification-cum-social reform plan, during an interview with Al Arabiya in April 2016. SV2030 vowed to transform Saudi Arabia, proposing fantastical ventures into the future while aggressively deploying capital abroad and opening the domestic economy up via debt issuance, investment code reform, contracting, and capital market reform. Knock-on effects for the world economy were imminent.

Facing volatility in the commodities market and growing financial vulnerabilities, the oil-dependent nation has since embarked on an effort to remake itself as a global economic powerhouse. Alongside ever expanding flows of crude to the east and deepening investment ties with China, Saudi Arabia’s moves on the home front looked primed to tilt the axis of global capital accumulation. The nine years since SV2030’s announcement have seen gains across a number of domains. The country has already cleared original targets for female labor-force participation and tourism. It is also likely to meet its goals in the capital markets. Courtesy of Aramco’s limited IPO, the Saudi Exchange now ranks as the ninth largest stock market in the world by market capitalization and the third largest among emerging markets.

SV2030 has also prompted an enormous wave of construction in its bid to reshape the country’s built environment. Despite its population of just 30 million, Saudi Arabia is poised to host the largest construction market in the world by 2028. Neom—the giga-project being conjured out in the western province of Tabuk along the northern shores of the Red Sea—is alone absorbing 20 percent of the global steel supply.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become an integral part of daily life, streamlining everything from search queries to complex decision-making. While AI tools offer convenience and efficiency, they also raise concerns about cognitive offloading—the process of delegating cognitive tasks to external aids. As reliance on AI grows, experts warn that it could diminish critical-thinking skills and alter fundamental cognitive processes. It is not about avoiding its use entirely; the incorporation of AI is essential for the advancement of our societies. (In fact, as will be seen later, it has been shown that a moderate use of AI can have a positive cognitive impact.) However, it is advisable to learn how to use it properly and in a balanced manner. These concerns were central to discussions at the AI for Humanity: Innovating for a Sustainable Digital Future session, led by Iliana Grosse-Buening, during the second edition of the

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become an integral part of daily life, streamlining everything from search queries to complex decision-making. While AI tools offer convenience and efficiency, they also raise concerns about cognitive offloading—the process of delegating cognitive tasks to external aids. As reliance on AI grows, experts warn that it could diminish critical-thinking skills and alter fundamental cognitive processes. It is not about avoiding its use entirely; the incorporation of AI is essential for the advancement of our societies. (In fact, as will be seen later, it has been shown that a moderate use of AI can have a positive cognitive impact.) However, it is advisable to learn how to use it properly and in a balanced manner. These concerns were central to discussions at the AI for Humanity: Innovating for a Sustainable Digital Future session, led by Iliana Grosse-Buening, during the second edition of the  Call it “A Tale of Two Satirists.”

Call it “A Tale of Two Satirists.” If you’re in the market for fishing bait anywhere in North America, and now even in parts of western Europe, odds are you’re buying a Canadian nightcrawler plucked from this stretch of land between Toronto and Windsor. These wild Canadian worms, who live so far beneath the surface of the soil that breeding or farming them is impractical, are hand-picked by a small army of workers, almost all immigrants from Southeast Asia, including generations of Vietnamese refugees and, more recently, temporary foreign workers from Thailand and Laos. It’s a niche sector of the western economy that’s exclusively sourced from this small corner of the province, and run primarily by family businesses passed from one generation to the next. In a given year, the more than $200 million industry sells between 500 and 700 million worms. But with changing demand, immigration labour policies, and the climate crisis, it’s also at an existential crossroads.

If you’re in the market for fishing bait anywhere in North America, and now even in parts of western Europe, odds are you’re buying a Canadian nightcrawler plucked from this stretch of land between Toronto and Windsor. These wild Canadian worms, who live so far beneath the surface of the soil that breeding or farming them is impractical, are hand-picked by a small army of workers, almost all immigrants from Southeast Asia, including generations of Vietnamese refugees and, more recently, temporary foreign workers from Thailand and Laos. It’s a niche sector of the western economy that’s exclusively sourced from this small corner of the province, and run primarily by family businesses passed from one generation to the next. In a given year, the more than $200 million industry sells between 500 and 700 million worms. But with changing demand, immigration labour policies, and the climate crisis, it’s also at an existential crossroads. As a materials scientist who

As a materials scientist who  In a recent series of videos, Avichay Adraee, the Arabic-language spokesperson for the Israeli military, relentlessly attacked Anas al-Sharif, an Al Jazeera correspondent in northern Gaza. On July 20, while reporting on a particularly harrowing scene from the courtyard of al-Shifa Hospital, al-Sharif broke down emotionally when an emaciated woman collapsed from hunger beside him, as an ambulance arrived carrying some of the dozens of people killed by Israeli soldiers that day while waiting for bags of flour. Adraee accused him of shedding “crocodile tears.” When al-Sharif called for a ceasefire, Adraee called him a “mouthpiece of intellectual terrorism.”

In a recent series of videos, Avichay Adraee, the Arabic-language spokesperson for the Israeli military, relentlessly attacked Anas al-Sharif, an Al Jazeera correspondent in northern Gaza. On July 20, while reporting on a particularly harrowing scene from the courtyard of al-Shifa Hospital, al-Sharif broke down emotionally when an emaciated woman collapsed from hunger beside him, as an ambulance arrived carrying some of the dozens of people killed by Israeli soldiers that day while waiting for bags of flour. Adraee accused him of shedding “crocodile tears.” When al-Sharif called for a ceasefire, Adraee called him a “mouthpiece of intellectual terrorism.” Americans are living ever more isolated lives. We get married later, start families later, have fewer children, and report more loneliness than ever before. Everyone suspects that new technology has something to do with this. But what if we’re also suffering from the failure of a very old technology?

Americans are living ever more isolated lives. We get married later, start families later, have fewer children, and report more loneliness than ever before. Everyone suspects that new technology has something to do with this. But what if we’re also suffering from the failure of a very old technology? T

T The last time I wrote about

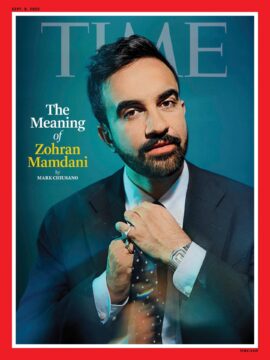

The last time I wrote about  It’s not easy to move around New York City as Zohran Mamdani anymore.

It’s not easy to move around New York City as Zohran Mamdani anymore. Three months after the 1929 Hebron massacre {which saw the deaths of nearly 70 Jews and scores of others maimed or wounded}, the celebrated historian Hans Kohn – active in the Zionist movement since 1909 – wrote the following letter: “I feel that I can no longer remain a leading official within the Zionist Organization… We pretend to be innocent victims. Of course, the Arabs attacked us this past August. Since they have no armies, they could not obey the rules of war. They perpetrated all the barbaric acts that are characteristic of a colonial revolt. But we are obliged to look into the deeper cause of this revolt. We have been in Palestine for twelve years [since the start of the British occupation] without having even once made a serious attempt at seeking through negotiations the consent of the indigenous people. We have been relying exclusively upon Great Britain’s military might. We have set ourselves goals which by their very nature had to lead to conflict with Arabs… for twelve years we pretended that the Arabs did not exist and were glad when we were not reminded of their existence.” (Jewish National and University Library 376/224, Kohn to Berthold Feiwel [1875–1937]. Jerusalem, 21 Nov. 1929).

Three months after the 1929 Hebron massacre {which saw the deaths of nearly 70 Jews and scores of others maimed or wounded}, the celebrated historian Hans Kohn – active in the Zionist movement since 1909 – wrote the following letter: “I feel that I can no longer remain a leading official within the Zionist Organization… We pretend to be innocent victims. Of course, the Arabs attacked us this past August. Since they have no armies, they could not obey the rules of war. They perpetrated all the barbaric acts that are characteristic of a colonial revolt. But we are obliged to look into the deeper cause of this revolt. We have been in Palestine for twelve years [since the start of the British occupation] without having even once made a serious attempt at seeking through negotiations the consent of the indigenous people. We have been relying exclusively upon Great Britain’s military might. We have set ourselves goals which by their very nature had to lead to conflict with Arabs… for twelve years we pretended that the Arabs did not exist and were glad when we were not reminded of their existence.” (Jewish National and University Library 376/224, Kohn to Berthold Feiwel [1875–1937]. Jerusalem, 21 Nov. 1929). S

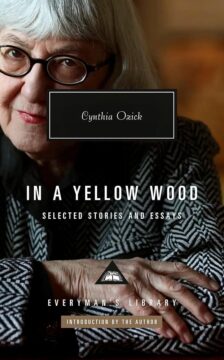

S You know you’re in a Cynthia Ozick short story when the wind is merciless and the leaves have dropped. It may already be snowing. In “Bloodshed,” we are greeted by the “icy scenes” that a gun-toting rationalist sees from a Greyhound bus on his way to a “town of the hasidim” outside New York City, where he is ultimately shamed and disarmed by a local rebbe. In “The Biographer’s Hat,” snowflakes adorn the fur collar of a crooked biographer who mouches off a proofreader and persuades her to falsely insert herself into his subject’s history. “A Mercenary” concludes with the haunting vision of a man lying dead “under the stone-white hanging stars of Poland…. Against the stones and under the snow.”

You know you’re in a Cynthia Ozick short story when the wind is merciless and the leaves have dropped. It may already be snowing. In “Bloodshed,” we are greeted by the “icy scenes” that a gun-toting rationalist sees from a Greyhound bus on his way to a “town of the hasidim” outside New York City, where he is ultimately shamed and disarmed by a local rebbe. In “The Biographer’s Hat,” snowflakes adorn the fur collar of a crooked biographer who mouches off a proofreader and persuades her to falsely insert herself into his subject’s history. “A Mercenary” concludes with the haunting vision of a man lying dead “under the stone-white hanging stars of Poland…. Against the stones and under the snow.” It would be easy to insist that LLMs are just objects, obviously. As an engineer I get it—it doesn’t matter how convincing the human affectations are, underneath the conversational interface is still nothing but data, algorithms, and matrix multiplication. Any projection of subject-hood is clearly just anthropomorphic nonsense.

It would be easy to insist that LLMs are just objects, obviously. As an engineer I get it—it doesn’t matter how convincing the human affectations are, underneath the conversational interface is still nothing but data, algorithms, and matrix multiplication. Any projection of subject-hood is clearly just anthropomorphic nonsense.