Melinda Moyer in The New York Times:

If you don’t suffer from migraine headaches, you probably know at least one person who does. Nearly 40 million Americans get them — 28 million of them women and girls — making migraine the second most disabling condition in the world after low back pain. Several studies have found that migraine became more frequent during the pandemic, too. I get migraine headaches, but thankfully they’re more bizarre than excruciating. Every few weeks, ocular migraine clouds my vision with strange zig-zagging lights for a half-hour; and once or twice a year I get attacks that cause temporary memory loss. (One came on while I was grocery shopping, and I couldn’t remember what month or year it was, what I was there to buy or how old my kids were.)

If you don’t suffer from migraine headaches, you probably know at least one person who does. Nearly 40 million Americans get them — 28 million of them women and girls — making migraine the second most disabling condition in the world after low back pain. Several studies have found that migraine became more frequent during the pandemic, too. I get migraine headaches, but thankfully they’re more bizarre than excruciating. Every few weeks, ocular migraine clouds my vision with strange zig-zagging lights for a half-hour; and once or twice a year I get attacks that cause temporary memory loss. (One came on while I was grocery shopping, and I couldn’t remember what month or year it was, what I was there to buy or how old my kids were.)

Despite its ubiquity, research on migraine has long been underfunded. The National Institutes of Health spent only $40 million on migraine research in 2021; by comparison, it spent $218 million researching epilepsy, which afflicts one-twelfth as many Americans. Why is this devastating condition so woefully understudied?

More here.

Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Anders Åslund, Robert D. Atkinson, Scott K.H. Bessent, Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Josef Braml, Patrick M. Cronin, Mansoor Dailami, John M. Deutch, Mohamed A. El-Erian, Gabriel J. Felbermayr, Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Harold James, Michael C. Kimmage, Gary N. Kleiman, James A. Lewis, Jennifer Lind, Robert A. Manning, Ewald Nowotny, Thomas Oatley, William A. Reinsch, Jeffrey D. Sachs, Daniel Sneider, Atman Trivedi, Edwin M. Truman, Daniel Twining, Nicolas Véron, and Marina v N. Whitman offer views in The International Economy:

Karmela Padavic-Callaghani in Aeon (Illustration by Richard Wilkinson):

Karmela Padavic-Callaghani in Aeon (Illustration by Richard Wilkinson): The American Colony, where I’m writing these lines on a table in the courtyard, is one physical incarnation of the thesis of

The American Colony, where I’m writing these lines on a table in the courtyard, is one physical incarnation of the thesis of  The epigraph to In the Castle of My Skin (“Something startles where I thought I was safe”) comes from Walt Whitman. Lamming takes heart from Whitman’s embrace of the sometimes paradoxical multiplicity that comes with giving one another room, with hearing and assimilating others’ viewpoints: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes).” There is even a subtle lesson in the names of Lamming’s first and last novels. As phrases, both In the Castle of My Skin and Natives of My Person allude to the complex interior state of the speaker. Both configure that interior as a populous place, shot through with other voices, other lives.

The epigraph to In the Castle of My Skin (“Something startles where I thought I was safe”) comes from Walt Whitman. Lamming takes heart from Whitman’s embrace of the sometimes paradoxical multiplicity that comes with giving one another room, with hearing and assimilating others’ viewpoints: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes).” There is even a subtle lesson in the names of Lamming’s first and last novels. As phrases, both In the Castle of My Skin and Natives of My Person allude to the complex interior state of the speaker. Both configure that interior as a populous place, shot through with other voices, other lives. Nick Fernandez was in hell — one filled with fire and skulls and the

Nick Fernandez was in hell — one filled with fire and skulls and the  “Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life.

“Ah, a nice old-fashioned novel,” the reader thinks, gliding through the opening pages of “Carnality.” The author, Lina Wolff, begins in a conventional close third-person perspective and quickly dispatches with the W questions. Who is the main character? A 45-year-old Swedish writer. What is she doing? Traveling on a writer’s grant. When? Present day, more or less. Where? Madrid. Why? To upend the tedium of her life. Early in her book about John Keats, Lucasta Miller calls Lord Byron an “aristocratic megastar.” That funny epithet is accurate for Byron’s more-than-superstar celebrity in his day. It also suggests the many ways Byron was the opposite of Keats. Miller quotes Byron, in a letter, referring to the younger and much less well-known poet as “Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are.”

Early in her book about John Keats, Lucasta Miller calls Lord Byron an “aristocratic megastar.” That funny epithet is accurate for Byron’s more-than-superstar celebrity in his day. It also suggests the many ways Byron was the opposite of Keats. Miller quotes Byron, in a letter, referring to the younger and much less well-known poet as “Jack Keats or Ketch or whatever his names are.” Around 1987, Sagan gave an uncannily prescient lecture to the Illinois state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union on the intersection between his area of expertise and theirs. We were fortunate to obtain a recording of that lecture, which we have transcribed, lightly edited, and annotated to update its historical allusions and contemporary relevance. Sagan spoke prophetically of the irrationality that plagued public discourse, the imperative of international cooperation, the dangers posed by advances in technology, and the threats to free speech and democracy in the United States. A 35-year retrospective reveals both increments of progress (some owing to Sagan’s own efforts) and

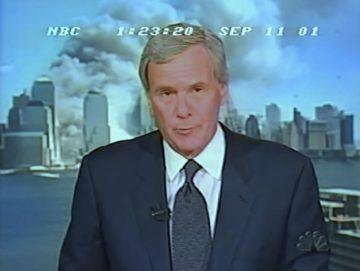

Around 1987, Sagan gave an uncannily prescient lecture to the Illinois state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union on the intersection between his area of expertise and theirs. We were fortunate to obtain a recording of that lecture, which we have transcribed, lightly edited, and annotated to update its historical allusions and contemporary relevance. Sagan spoke prophetically of the irrationality that plagued public discourse, the imperative of international cooperation, the dangers posed by advances in technology, and the threats to free speech and democracy in the United States. A 35-year retrospective reveals both increments of progress (some owing to Sagan’s own efforts) and If you ask Americans when was the last time they recall feeling truly united as a country, people over the age of thirty will almost certainly point to the aftermath of 9/11. However briefly, everyone was united in grief and anger, and a palpable sense of social solidarity pervaded our communities.

If you ask Americans when was the last time they recall feeling truly united as a country, people over the age of thirty will almost certainly point to the aftermath of 9/11. However briefly, everyone was united in grief and anger, and a palpable sense of social solidarity pervaded our communities. Where You End and I Begin isn’t in fact that book. Instead, it’s something more amorphous, more exposing. It started as a collaboration between the author and her mother but after Cessie withdrew, it ceased being a journalistic investigation into the Horseman and his crimes (there were other child victims) and became an intimate voyage into the deepest, darkest heart of motherhood and daughterhood, musing too on consent, victim narratives and the ownership of stories. The result is a work of probing insight and undaunted compassion; one that’s fearlessly engrossing, frequently funny and sometimes plain hair-raising.

Where You End and I Begin isn’t in fact that book. Instead, it’s something more amorphous, more exposing. It started as a collaboration between the author and her mother but after Cessie withdrew, it ceased being a journalistic investigation into the Horseman and his crimes (there were other child victims) and became an intimate voyage into the deepest, darkest heart of motherhood and daughterhood, musing too on consent, victim narratives and the ownership of stories. The result is a work of probing insight and undaunted compassion; one that’s fearlessly engrossing, frequently funny and sometimes plain hair-raising. During the final months of the Second World War, the publisher Alfred A. Knopf commissioned a reader’s report, consisting of a form on blue paper with a few queries, regarding a translated novel it was considering by an Icelander named Halldór Laxness. Section B of the form instructed the reader, “If you recommend us to publish the book give your chief reason in a single sentence.” The reader replied, “Those who read this book will never forget it.”

During the final months of the Second World War, the publisher Alfred A. Knopf commissioned a reader’s report, consisting of a form on blue paper with a few queries, regarding a translated novel it was considering by an Icelander named Halldór Laxness. Section B of the form instructed the reader, “If you recommend us to publish the book give your chief reason in a single sentence.” The reader replied, “Those who read this book will never forget it.” Why is it that we may agree in advance that a particular result is a fair test of our theory, then see so much more when the result is known? Why can’t we anticipate our response to results that we do not expect to materialize? The psychology of this is straightforward. The normal flow of reasoning is forward from what you believe to a possible consequence. When someone proposes a serious critical test, you cannot get from your theory to the result without adding an extra wrinkle to the theory. The extra wrinkle is hard to find—if it were easy, this would not be a serious critical test. On the other hand, the result probably follows from the adversary’s theory. The lazy solution is to concede provisionally.

Why is it that we may agree in advance that a particular result is a fair test of our theory, then see so much more when the result is known? Why can’t we anticipate our response to results that we do not expect to materialize? The psychology of this is straightforward. The normal flow of reasoning is forward from what you believe to a possible consequence. When someone proposes a serious critical test, you cannot get from your theory to the result without adding an extra wrinkle to the theory. The extra wrinkle is hard to find—if it were easy, this would not be a serious critical test. On the other hand, the result probably follows from the adversary’s theory. The lazy solution is to concede provisionally. Natural immunity induced by infection with SARS-CoV-2 provides a strong shield against reinfection by a pre-Omicron variant for 16 months or longer, according to a study

Natural immunity induced by infection with SARS-CoV-2 provides a strong shield against reinfection by a pre-Omicron variant for 16 months or longer, according to a study