Peter Filkins at Salmagundi:

The role of poet-critics is a special one in any literature. Practitioners of the art, they also reveal its underpinnings, an activity that involves more than a mere thumbs-up-or-down review. Instead, by shaping whom and how we read, their influence can be considerable. Randall Jarrell famously dissected poets in regards to their best, or most often, worst tendencies. T.S. Eliot, on the other hand, took the high road, gazing calmly over the centuries while situating poets amid a cultural landscape over which he sought to reign. Usually, however, the stakes are not that high, for most often the role of the poet-critic is neither to delineate nor disseminate, but rather to illuminate. In such manner the main subject of the poet-critic, versus that of the literary critic or reviewer, is poetry itself. Reviewers tell us what a book of poems is “about”; the poet-critic reminds us of what poetry is and can be.

The role of poet-critics is a special one in any literature. Practitioners of the art, they also reveal its underpinnings, an activity that involves more than a mere thumbs-up-or-down review. Instead, by shaping whom and how we read, their influence can be considerable. Randall Jarrell famously dissected poets in regards to their best, or most often, worst tendencies. T.S. Eliot, on the other hand, took the high road, gazing calmly over the centuries while situating poets amid a cultural landscape over which he sought to reign. Usually, however, the stakes are not that high, for most often the role of the poet-critic is neither to delineate nor disseminate, but rather to illuminate. In such manner the main subject of the poet-critic, versus that of the literary critic or reviewer, is poetry itself. Reviewers tell us what a book of poems is “about”; the poet-critic reminds us of what poetry is and can be.

more here.

Still, national images are always subject to fluctuation, and at least in the West, historical shifts in the perception of Japan have been particularly dramatic. A much darker view of the country—as a land of ferocious militarists caught up in a death cult—was already fading when I was a boy in the early postwar years. U.S. soldiers returning from Japan showed color slides of Kyoto temples and stately young women in kimonos. Soon Japan was being described as the proverbial phoenix rising from the ashes, now firmly committed to democracy and staunchly allied with its former enemy, the United States. Growing interest in Japan and Japanese culture, particularly in the late 1970s and early 1980s, led to an exaggerated picture of the nation’s strength. Admiration was mixed with misplaced envy, with “Japan Incorporated” now perceived as a new kind of Imperial Japan, with black-suited businessmen replacing sword-wielding warriors. Teaching Japanese and linguistics in a liberal-arts college in upstate New York for two years in the late 1980s, I met students eager to live in Japan long enough to master the language, obtain MBAs from a prestigious American institution, and thereby make their fortunes. Then in the early 1990s, the economic bubble burst. The rising superpower was now suddenly being described with another cliché—the land of the setting sun.

Still, national images are always subject to fluctuation, and at least in the West, historical shifts in the perception of Japan have been particularly dramatic. A much darker view of the country—as a land of ferocious militarists caught up in a death cult—was already fading when I was a boy in the early postwar years. U.S. soldiers returning from Japan showed color slides of Kyoto temples and stately young women in kimonos. Soon Japan was being described as the proverbial phoenix rising from the ashes, now firmly committed to democracy and staunchly allied with its former enemy, the United States. Growing interest in Japan and Japanese culture, particularly in the late 1970s and early 1980s, led to an exaggerated picture of the nation’s strength. Admiration was mixed with misplaced envy, with “Japan Incorporated” now perceived as a new kind of Imperial Japan, with black-suited businessmen replacing sword-wielding warriors. Teaching Japanese and linguistics in a liberal-arts college in upstate New York for two years in the late 1980s, I met students eager to live in Japan long enough to master the language, obtain MBAs from a prestigious American institution, and thereby make their fortunes. Then in the early 1990s, the economic bubble burst. The rising superpower was now suddenly being described with another cliché—the land of the setting sun. It just so happens Fuller’s popular legacy is bloated, like the geodesic domes he is most easily identified with today. Alec Nevala-Lee’s new biography, Inventor of the Future, fact-checks Fuller’s legend and then corrects the record. Nevala-Lee himself discovered Fuller through the pages of the counterculture bible, Whole Earth Catalog, and grew up admiring him. But, in writing Fuller’s biography, he resists the hypnotic whirlpool surrounding Fuller. Known to be an unreliable narrator of his own life, Fuller inflated numbers, misrepresented facts, and invented stories of epiphanies and revelations. The legends and myths solidified with their countless retellings — but, really, how dare anyone doubt a sage? He lied about high school grades he never obtained, college courses never taken, daring rescues never made, and those are just the easiest to fact-check. Whenever possible, Nevala-Lee corrects Fuller as he cites him, the embellished version followed by the correct, less glamorous version. At other times, the reader is left wondering if what’s written on the page really happened.

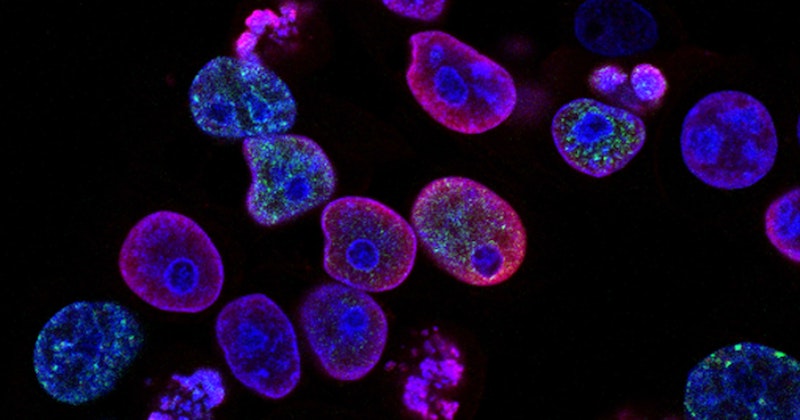

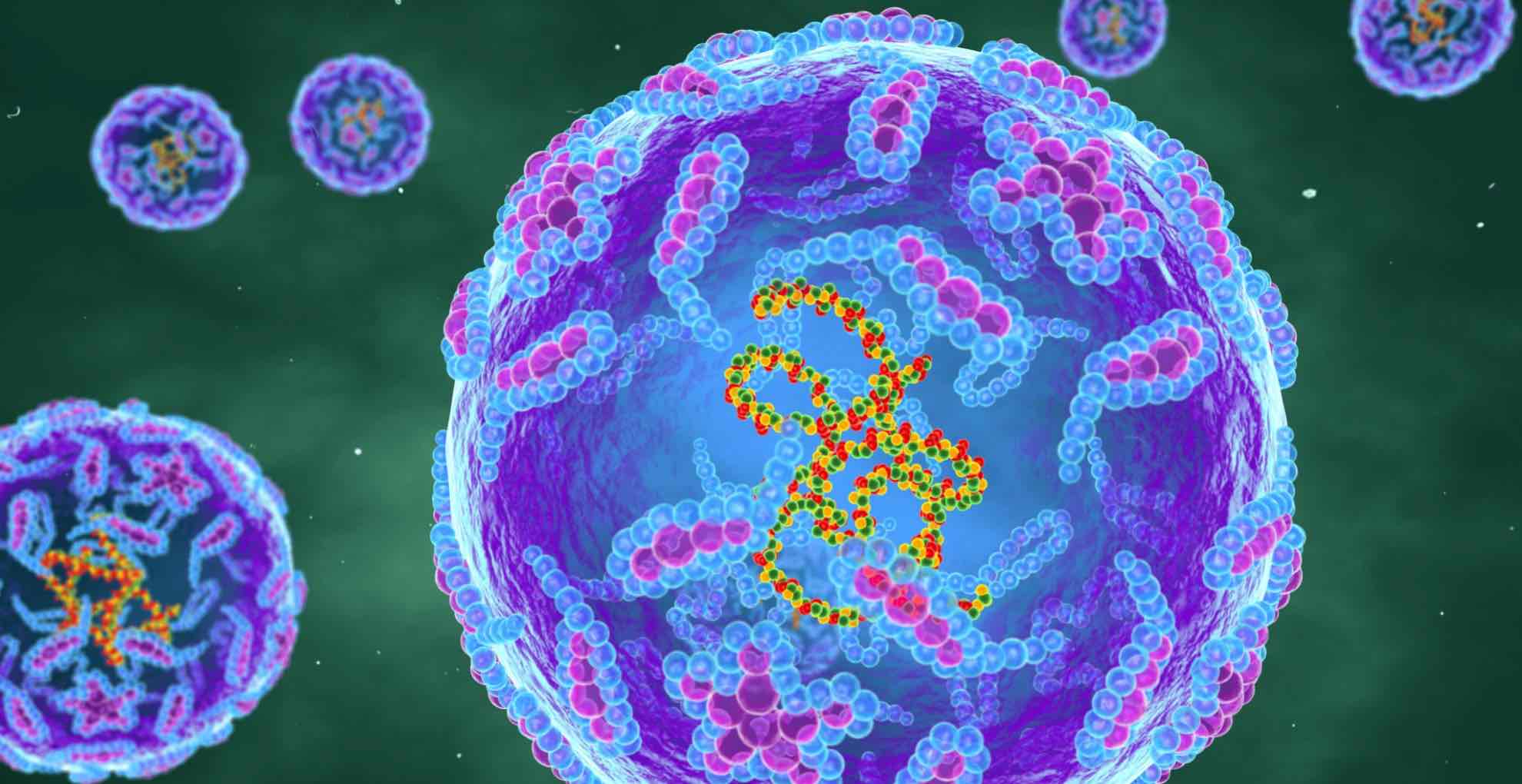

It just so happens Fuller’s popular legacy is bloated, like the geodesic domes he is most easily identified with today. Alec Nevala-Lee’s new biography, Inventor of the Future, fact-checks Fuller’s legend and then corrects the record. Nevala-Lee himself discovered Fuller through the pages of the counterculture bible, Whole Earth Catalog, and grew up admiring him. But, in writing Fuller’s biography, he resists the hypnotic whirlpool surrounding Fuller. Known to be an unreliable narrator of his own life, Fuller inflated numbers, misrepresented facts, and invented stories of epiphanies and revelations. The legends and myths solidified with their countless retellings — but, really, how dare anyone doubt a sage? He lied about high school grades he never obtained, college courses never taken, daring rescues never made, and those are just the easiest to fact-check. Whenever possible, Nevala-Lee corrects Fuller as he cites him, the embellished version followed by the correct, less glamorous version. At other times, the reader is left wondering if what’s written on the page really happened. The idea that mutations cause cancer remains the dominant paradigm. A special issue of Nature from 2020 wrote: “Cancer is a disease of the genome, caused by a cell’s acquisition of somatic mutations in key cancer genes.” Yet over the last decade it has looked as if the juggernaut has rolled too far. It has certainly failed to deliver on its promise in terms of therapies. So why hasn’t the death rate from malignant cancer changed since 1971?

The idea that mutations cause cancer remains the dominant paradigm. A special issue of Nature from 2020 wrote: “Cancer is a disease of the genome, caused by a cell’s acquisition of somatic mutations in key cancer genes.” Yet over the last decade it has looked as if the juggernaut has rolled too far. It has certainly failed to deliver on its promise in terms of therapies. So why hasn’t the death rate from malignant cancer changed since 1971?

In popular culture, Tudor noblewoman

In popular culture, Tudor noblewoman  You might think that the FBI search at Mar-a-Lago yesterday would provide a welcome opportunity for a Trump-weary Republican Party. This would be an entirely postpresidential scandal for Donald Trump. Unlike his two impeachments, this time any legal jeopardy is a purely personal Trump problem. Big donors and Fox News management have been trying for months to nudge the party away from Trump. Here was the perfect chance. Just say “No comment” and let justice take its course.

You might think that the FBI search at Mar-a-Lago yesterday would provide a welcome opportunity for a Trump-weary Republican Party. This would be an entirely postpresidential scandal for Donald Trump. Unlike his two impeachments, this time any legal jeopardy is a purely personal Trump problem. Big donors and Fox News management have been trying for months to nudge the party away from Trump. Here was the perfect chance. Just say “No comment” and let justice take its course. For artists, middle age is freighted with aesthetic drama. For poets, it’s also often a period of formal metamorphoses. Midlife crisis is a term too loaded with risible associations to be useful here. The transformation seems more a matter of taking inventory, the poet alighting on a doubt or an intuition and having a good look around. Evolutions during this period are frequent and substantial: the seriocomic alibi of Brazil in

For artists, middle age is freighted with aesthetic drama. For poets, it’s also often a period of formal metamorphoses. Midlife crisis is a term too loaded with risible associations to be useful here. The transformation seems more a matter of taking inventory, the poet alighting on a doubt or an intuition and having a good look around. Evolutions during this period are frequent and substantial: the seriocomic alibi of Brazil in  Derbew’s book arrives at a pivotal moment in classical studies. The past years have seen debates on the

Derbew’s book arrives at a pivotal moment in classical studies. The past years have seen debates on the  Humans, frogs and many other widely studied animals start as a single cell that immediately divides again and again into separate cells. In crickets and most other insects, initially just the cell nucleus divides, forming many nuclei that travel throughout the shared cytoplasm and only later form cellular membranes of their own. In 2019, Stefano Di Talia, a quantitative developmental biologist at Duke University,

Humans, frogs and many other widely studied animals start as a single cell that immediately divides again and again into separate cells. In crickets and most other insects, initially just the cell nucleus divides, forming many nuclei that travel throughout the shared cytoplasm and only later form cellular membranes of their own. In 2019, Stefano Di Talia, a quantitative developmental biologist at Duke University,  Some, including me, may be suffering from Chronic Password Fatigue Syndrome (CPFS would be the acronym). Scientific publishing, peer review and paywalls are a very problematic area that contributes to disparities around the world, among other

Some, including me, may be suffering from Chronic Password Fatigue Syndrome (CPFS would be the acronym). Scientific publishing, peer review and paywalls are a very problematic area that contributes to disparities around the world, among other  On April 3, 1911, Edna St. Vincent Millay took her first lover. She was 19 years old, and she engaged herself to this man with a ring that “came to me in a fortune-cake” and was “the symbol of all earthly happiness.” Millay had just graduated from high school and had taken charge of running the household while her mother worked as a traveling nurse. She fixed her younger sisters dinner, washed and mended all their clothes, and entertained their guests. Her lover had no name and no body; he was a figment she’d conjured up to help her get through the stress and loneliness of being a teenage caretaker. This first lover, her “shadow,” is not often recounted among the many others she later had, but Millay had various ways of making these exhausting days of her early adulthood endlessly charming and alive. In one note to her lover, she describes the chafing dish she served her siblings’ dinner on, which she called James, and jokes, “Why don’t you come over some evening and have something on ‘James’—doesn’t that sound dreadful—‘have something on James’!”

On April 3, 1911, Edna St. Vincent Millay took her first lover. She was 19 years old, and she engaged herself to this man with a ring that “came to me in a fortune-cake” and was “the symbol of all earthly happiness.” Millay had just graduated from high school and had taken charge of running the household while her mother worked as a traveling nurse. She fixed her younger sisters dinner, washed and mended all their clothes, and entertained their guests. Her lover had no name and no body; he was a figment she’d conjured up to help her get through the stress and loneliness of being a teenage caretaker. This first lover, her “shadow,” is not often recounted among the many others she later had, but Millay had various ways of making these exhausting days of her early adulthood endlessly charming and alive. In one note to her lover, she describes the chafing dish she served her siblings’ dinner on, which she called James, and jokes, “Why don’t you come over some evening and have something on ‘James’—doesn’t that sound dreadful—‘have something on James’!” In the U.S., public health agencies generally don’t test sewage for polio. Instead, they wait for people to show up sick in doctor’s offices or hospitals — a reactive strategy that can give this stealthy virus more time to circulate silently through the community before it is detected.

In the U.S., public health agencies generally don’t test sewage for polio. Instead, they wait for people to show up sick in doctor’s offices or hospitals — a reactive strategy that can give this stealthy virus more time to circulate silently through the community before it is detected. Many people have recognized the centrality of polarization and offered solutions for how to get out of it. Among these are: institutional changes, especially to our electoral laws, that would restructure the incentives under which politicians operate; the growth of a third, centrist party that grabs the middle ground from the extreme wings of the existing two; and grassroots movements to build moderation and understanding from the bottom up. All of these will be important components of depolarization, but none of them will be sufficient by themselves or take place soon enough to solve the problem.

Many people have recognized the centrality of polarization and offered solutions for how to get out of it. Among these are: institutional changes, especially to our electoral laws, that would restructure the incentives under which politicians operate; the growth of a third, centrist party that grabs the middle ground from the extreme wings of the existing two; and grassroots movements to build moderation and understanding from the bottom up. All of these will be important components of depolarization, but none of them will be sufficient by themselves or take place soon enough to solve the problem. I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.

I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.