Aditya Chakrabortty in The Guardian:

The sixth-richest country in the world faces a winter of humanitarian crisis. Unless the government acts now, millions of Britons will be unable to keep their homes warm. Some will die while, as the NHS warns, many more will fall seriously ill. Schools, hospitals and care homes across the country must choose between busting their budgets or freezing. Countless shops and businesses will close, never to open again. More than 70% of pubs are preparing for last orders, while any restaurant, cafe, chippy or kebab shop must now face existential threat, thanks to a quadrupling of their energy bills, surging food prices and a recession that will kill discretionary spending. As economic catastrophes go, this looks far bigger than the 2008 crash. It promises to reshape our everyday lives and social fabric.

The sixth-richest country in the world faces a winter of humanitarian crisis. Unless the government acts now, millions of Britons will be unable to keep their homes warm. Some will die while, as the NHS warns, many more will fall seriously ill. Schools, hospitals and care homes across the country must choose between busting their budgets or freezing. Countless shops and businesses will close, never to open again. More than 70% of pubs are preparing for last orders, while any restaurant, cafe, chippy or kebab shop must now face existential threat, thanks to a quadrupling of their energy bills, surging food prices and a recession that will kill discretionary spending. As economic catastrophes go, this looks far bigger than the 2008 crash. It promises to reshape our everyday lives and social fabric.

That is the meaning of today’s statement from the watchdog Ofgem. The new price cap of £3,549 it has set for household energy bills is almost triple that of last winter, and for many it is simply unaffordable. When it kicks in, at the start of October, 25% of Britons will not be able to pay their fuel bills.

More here.

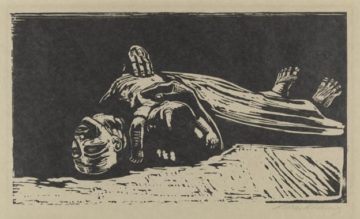

In October 1943, Henrich Himmler gave two speeches in Posen, Poland. The Posen speeches, as they have come to be known, represent the first time a member of Hitler’s Cabinet had publicly articulated the Nazi policy of the extermination of the Jews. Himmler, the head of the SS, acknowledged that the task was not without personal difficulty—to see 1,000 corpses and remain “decent” was hard, he said, but the experience made those who carried out the exterminations “tough.” What about the killing of women and children? According to Himmler, they needed to be exterminated because they might become—or give birth to—avengers of their fathers. In the end, he said, “the difficult decision had to be made to have this people disappear from the earth.” Empathy, while a natural human response, needed to be set aside.

In October 1943, Henrich Himmler gave two speeches in Posen, Poland. The Posen speeches, as they have come to be known, represent the first time a member of Hitler’s Cabinet had publicly articulated the Nazi policy of the extermination of the Jews. Himmler, the head of the SS, acknowledged that the task was not without personal difficulty—to see 1,000 corpses and remain “decent” was hard, he said, but the experience made those who carried out the exterminations “tough.” What about the killing of women and children? According to Himmler, they needed to be exterminated because they might become—or give birth to—avengers of their fathers. In the end, he said, “the difficult decision had to be made to have this people disappear from the earth.” Empathy, while a natural human response, needed to be set aside. The naked mole rat may not be much to look at, but it has much to say. The wrinkled, whiskered rodents, which live, like many ants do, in large, underground colonies, have an elaborate vocal repertoire. They whistle, trill and twitter; grunt, hiccup and hiss. And when two of the voluble rats meet in a dark tunnel, they exchange a standard salutation. “They’ll make a soft chirp, and then a repeating soft chirp,” said Alison Barker, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, in Germany. “They have a little conversation.” Hidden in this everyday exchange is a wealth of social information, Dr. Barker and her colleagues discovered when they used machine-learning algorithms to analyze 36,000 soft chirps recorded in seven mole rat colonies.

The naked mole rat may not be much to look at, but it has much to say. The wrinkled, whiskered rodents, which live, like many ants do, in large, underground colonies, have an elaborate vocal repertoire. They whistle, trill and twitter; grunt, hiccup and hiss. And when two of the voluble rats meet in a dark tunnel, they exchange a standard salutation. “They’ll make a soft chirp, and then a repeating soft chirp,” said Alison Barker, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, in Germany. “They have a little conversation.” Hidden in this everyday exchange is a wealth of social information, Dr. Barker and her colleagues discovered when they used machine-learning algorithms to analyze 36,000 soft chirps recorded in seven mole rat colonies. Betroffenheitskitsch. It is not an easy word to say. That’s because it is German and Germans love to make compound words. The core of the word is the adjective betroffen, which means ‘affected’, but also ‘concerned’, and even ‘shocked’ or ‘stricken’. Betroffenheit is the noun and can be translated as ‘shock’, ‘consternation’, ‘concern’. Finally, we add the word kitsch, which makes the whole thing, well, kitschy. Betroffenheitskitsch is shock or deep concern that has been taken to the level of kitsch.

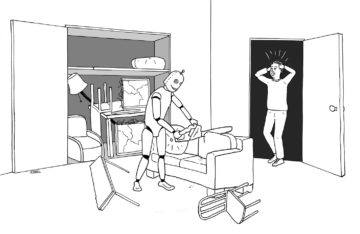

Betroffenheitskitsch. It is not an easy word to say. That’s because it is German and Germans love to make compound words. The core of the word is the adjective betroffen, which means ‘affected’, but also ‘concerned’, and even ‘shocked’ or ‘stricken’. Betroffenheit is the noun and can be translated as ‘shock’, ‘consternation’, ‘concern’. Finally, we add the word kitsch, which makes the whole thing, well, kitschy. Betroffenheitskitsch is shock or deep concern that has been taken to the level of kitsch. From a showmanship standpoint, Google’s new robot project

From a showmanship standpoint, Google’s new robot project  There is no human endeavor that does not have a theory of it — a set of ideas about what makes it work and how to do it well. Music is no exception, popular music included — there are reasons why certain keys, chord changes, and rhythmic structures have proven successful over the years. Nobody has done more to help people understand the theoretical underpinnings of popular music than today’s guest, Rick Beato. His YouTube videos dig into how songs work and what makes them great. We talk about music theory and how it contributes to our appreciation of all kinds of music.

There is no human endeavor that does not have a theory of it — a set of ideas about what makes it work and how to do it well. Music is no exception, popular music included — there are reasons why certain keys, chord changes, and rhythmic structures have proven successful over the years. Nobody has done more to help people understand the theoretical underpinnings of popular music than today’s guest, Rick Beato. His YouTube videos dig into how songs work and what makes them great. We talk about music theory and how it contributes to our appreciation of all kinds of music. However difficult it is to properly gauge the significance of historical events while still living through them, we can surely already state with confidence that the Covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine together constitute a truly seismic and transformative sequence of years for the world.

However difficult it is to properly gauge the significance of historical events while still living through them, we can surely already state with confidence that the Covid pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine together constitute a truly seismic and transformative sequence of years for the world. THE WRITER AND SCHOLAR

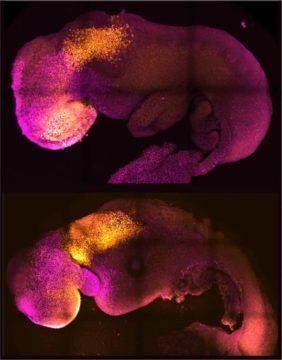

THE WRITER AND SCHOLAR The recipe for mammalian life is simple: take an egg, add sperm and wait. But two new papers demonstrate that there’s another way. Under the right conditions, stem cells can divide and self-organize into an embryo on their own. In studies published in Cell and Nature this month, two groups report that they have grown synthetic mouse embryos for longer than ever before. The embryos grew for 8.5 days, long enough for them to develop distinct organs — a beating heart, a gut tube and even neural folds.

The recipe for mammalian life is simple: take an egg, add sperm and wait. But two new papers demonstrate that there’s another way. Under the right conditions, stem cells can divide and self-organize into an embryo on their own. In studies published in Cell and Nature this month, two groups report that they have grown synthetic mouse embryos for longer than ever before. The embryos grew for 8.5 days, long enough for them to develop distinct organs — a beating heart, a gut tube and even neural folds. Masha Gessen in The New Yorker (Photograph by Maxim Shemetov / Reuters):

Masha Gessen in The New Yorker (Photograph by Maxim Shemetov / Reuters): Fathimath Musthaq in Phenomenal World:

Fathimath Musthaq in Phenomenal World: P

P Naturalness is the muse’s great gift. Like Helga Testorf, who merely had to stand still for Andrew Wyeth to want to transpose her spirit, Sedgwick had only to walk and talk for Warhol to track her every move on film. “Andy always picks people because they have an amazing sort of essential flame, and he brings it out for the purposes of his films,” the curator Henry Geldzahler once said. “He never takes anybody who has nothing and makes them into something. What he did was recognize that Edie was this amazing creature, and he was able to make her more Edie so that when he got it on camera it would be made available to everybody.” Warhol’s movies captured Sedgwick just being herself: putting on makeup, lying in bed, perching on a couch arm while looking about the room. She appeared in more than a dozen films, such as “Face,” a seventy-minute-long closeup, and “Afternoon,” a scripted “chamber opera” in which Sedgwick and friends gas around in her apartment, high on amphetamines. Sedgwick Wohl, who has spent decades watching her sister on film, observes her as if looking through a high-powered telescope. “What they saw in her was not talent but simply the way she was, transcribed onto the screen,” Sedgwick Wohl writes.

Naturalness is the muse’s great gift. Like Helga Testorf, who merely had to stand still for Andrew Wyeth to want to transpose her spirit, Sedgwick had only to walk and talk for Warhol to track her every move on film. “Andy always picks people because they have an amazing sort of essential flame, and he brings it out for the purposes of his films,” the curator Henry Geldzahler once said. “He never takes anybody who has nothing and makes them into something. What he did was recognize that Edie was this amazing creature, and he was able to make her more Edie so that when he got it on camera it would be made available to everybody.” Warhol’s movies captured Sedgwick just being herself: putting on makeup, lying in bed, perching on a couch arm while looking about the room. She appeared in more than a dozen films, such as “Face,” a seventy-minute-long closeup, and “Afternoon,” a scripted “chamber opera” in which Sedgwick and friends gas around in her apartment, high on amphetamines. Sedgwick Wohl, who has spent decades watching her sister on film, observes her as if looking through a high-powered telescope. “What they saw in her was not talent but simply the way she was, transcribed onto the screen,” Sedgwick Wohl writes. Are you prepared for a vision of sizzling sexuality? Picture this. A woman dressed in brown suede brogues and a below-the-knee skirt, her legs obscured by stockings. Sandy-gray hair. A discreet brooch pinned to her blouse, a formal manner of speaking, a keen interest in antiquity and a tendency to suffer from migraines. These qualities may not scream “racy” or “seductive” or “exotic” to you, but you are not the narrator of Julian Barnes’s 25th book.

Are you prepared for a vision of sizzling sexuality? Picture this. A woman dressed in brown suede brogues and a below-the-knee skirt, her legs obscured by stockings. Sandy-gray hair. A discreet brooch pinned to her blouse, a formal manner of speaking, a keen interest in antiquity and a tendency to suffer from migraines. These qualities may not scream “racy” or “seductive” or “exotic” to you, but you are not the narrator of Julian Barnes’s 25th book.