Josh Lambert in JSTOR Daily:

You don’t have to dig deeply to discover the stress produced in many academics and writers by the constant stream of requests for letters of recommendation and book blurbs from former students, current ones, and colleagues.

These requests provoke anxiety not only because of the time they absorb, but also because of the ethical questions they pose: Can I in good conscience blurb this book despite the problems I have with it? Is it right that the students with the confidence to ask for letters get more support than the shy ones? Must I blurb this book effusively, simply because its author blurbed my own with enthusiasm? (The terror that a cycle of reciprocity might spiral forever upward is captured in a 1992 poem in The American Scholar, “A Farewell to Blurbs,” which ends with one poet asking another to just call the whole thing off: “I still ask you to agree / That if I say no more about your poems, you’ll do the same for me.”)

If such anxieties sound familiar, be glad that you’re not Lionel Trilling. When he was flying high in the 1950s, as possibly the most celebrated professor in the country, his recommendations held astonishing power. He knew they got results.

More here.

Three chemists who pioneered a useful technique called click chemistry to join molecules together efficiently have won this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Three chemists who pioneered a useful technique called click chemistry to join molecules together efficiently have won this year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Love hungers for knowledge. For someone newly in love, nothing is better than learning about the beloved, nothing better than revealing yourself to them in turn. “The talk of lovers who have just declared their love,” writes Iris Murdoch in The Bell (1958), “is one of life’s most sweet delights. . . . Each one in haste to declare all that he is, so that no part of his being escapes the hallowing touch.”

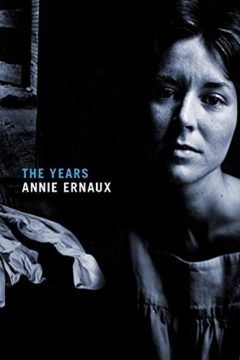

Love hungers for knowledge. For someone newly in love, nothing is better than learning about the beloved, nothing better than revealing yourself to them in turn. “The talk of lovers who have just declared their love,” writes Iris Murdoch in The Bell (1958), “is one of life’s most sweet delights. . . . Each one in haste to declare all that he is, so that no part of his being escapes the hallowing touch.” “I have always wanted to write the sort of book that I find it impossible to talk about afterward, the sort of book that makes it impossible for me to withstand the gaze of others,” writes Annie Ernaux’s narrator near the end of her 1998 autofiction, Shame. Ernaux takes the sentiment further in the opening lines of her 2008 book, The Possession: “I have always wanted to write as if I would be gone when the book was published. To write as if I were about to die—no more judges.”

“I have always wanted to write the sort of book that I find it impossible to talk about afterward, the sort of book that makes it impossible for me to withstand the gaze of others,” writes Annie Ernaux’s narrator near the end of her 1998 autofiction, Shame. Ernaux takes the sentiment further in the opening lines of her 2008 book, The Possession: “I have always wanted to write as if I would be gone when the book was published. To write as if I were about to die—no more judges.” The Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck, who lived from 1886 to 1957, is little known outside his native land, but his moments of fame have been as striking as they are strange. For one thing, Schoeck gained the admiration of several leading writers of the twentieth century. Hermann Hesse ranked Schoeck’s songs alongside those of Schubert and Schumann; James Joyce considered him a rival to Stravinsky; Thomas Mann also thought highly of him. A further quiver of notoriety followed in the nineteen-seventies, when, as Calvin Trillin

The Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck, who lived from 1886 to 1957, is little known outside his native land, but his moments of fame have been as striking as they are strange. For one thing, Schoeck gained the admiration of several leading writers of the twentieth century. Hermann Hesse ranked Schoeck’s songs alongside those of Schubert and Schumann; James Joyce considered him a rival to Stravinsky; Thomas Mann also thought highly of him. A further quiver of notoriety followed in the nineteen-seventies, when, as Calvin Trillin  O

O F

F IT WAS JUST THE KIND

IT WAS JUST THE KIND D

D Jon Stewart has a dream where he walks out onto the brightly lit set of a new TV show. He has worked for years to build this show. It’s the answer to everything wrong with the news media.

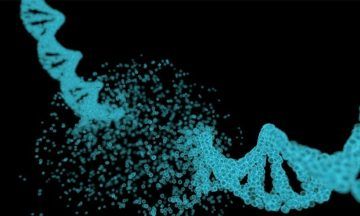

Jon Stewart has a dream where he walks out onto the brightly lit set of a new TV show. He has worked for years to build this show. It’s the answer to everything wrong with the news media. For the first time, a Nobel Prize recognized the field of anthropology, the study of humanity. Svante Pääbo, a pioneer in the study of ancient DNA, or aDNA, was awarded the 2022

For the first time, a Nobel Prize recognized the field of anthropology, the study of humanity. Svante Pääbo, a pioneer in the study of ancient DNA, or aDNA, was awarded the 2022  The

The

E

E