Tim Caro in Nature:

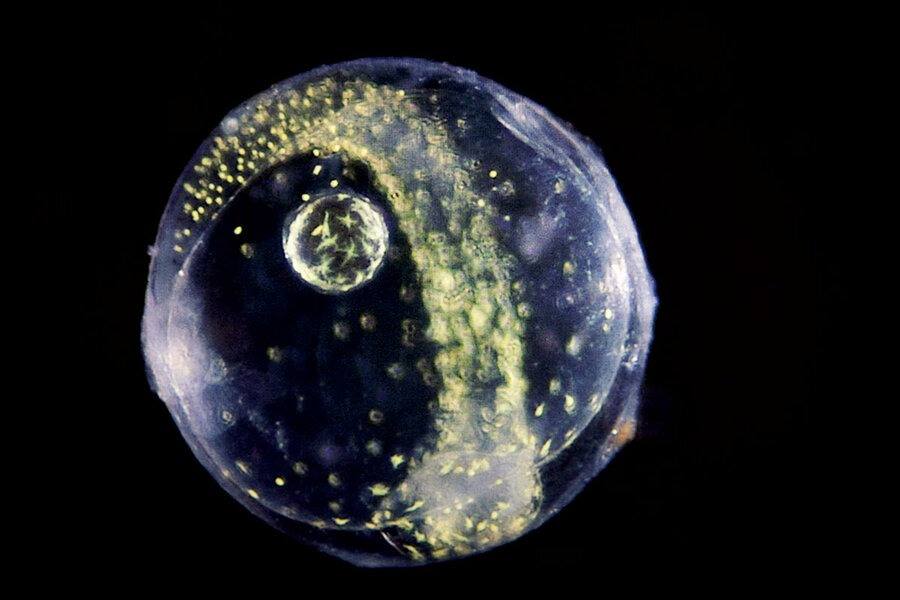

The breathtaking palette of colours seen in nature is the fuel that drives many of us to become biologists, and is the reason why some researchers try to understand the biological basis of animal and plant coloration1. Normally, the drivers of such evolutionary processes can be bracketed into categories that result in colour for protection, signalling or physiological reasons2. Writing in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Falk et al.3 propose an evolutionary driver with a new twist.

The breathtaking palette of colours seen in nature is the fuel that drives many of us to become biologists, and is the reason why some researchers try to understand the biological basis of animal and plant coloration1. Normally, the drivers of such evolutionary processes can be bracketed into categories that result in colour for protection, signalling or physiological reasons2. Writing in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Falk et al.3 propose an evolutionary driver with a new twist.

Variation in coloration occurs between species but also within them — leopards (Panthera pardus), for example, can have a black or mottled tawny coat, and the flowers of Iris lutescens can be purple or yellow. These colour differences are variations in form called polymorphisms. For some scientists, it is sufficient to know that such colour polymorphisms exist, but for others, the underlying genetics of such variation must be understood. Formally, a polymorphism is “the occurrence together in the same habitat of two or more distinct forms of a species in such proportions that the rarest of them cannot be maintained by recurrent mutation”4. In other words, for the rare forms to be present, a new mutation doesn’t have to occur each time.

More here.

The issue is that Newton’s laws work about twice as well as we might expect them to. They describe the world we move through every day – the world of people, the hands that move around a clock and even

The issue is that Newton’s laws work about twice as well as we might expect them to. They describe the world we move through every day – the world of people, the hands that move around a clock and even  Spring came early this year in the high mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan, a remote border region of Pakistan. Record temperatures in March and April hastened melting of the Shisper Glacier, creating a lake that swelled and, on May 7, burst through an ice dam. A torrent of water and debris flooded the valley below, damaging fields and houses, wrecking two power plants, and washing away parts of the main highway and a

Spring came early this year in the high mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan, a remote border region of Pakistan. Record temperatures in March and April hastened melting of the Shisper Glacier, creating a lake that swelled and, on May 7, burst through an ice dam. A torrent of water and debris flooded the valley below, damaging fields and houses, wrecking two power plants, and washing away parts of the main highway and a  One of the most enduring ideas in economics is that free markets bring peace between countries. It comes from the notion that commerce drives humans to follow their mutual material interests rather than make destructive war due to passions.

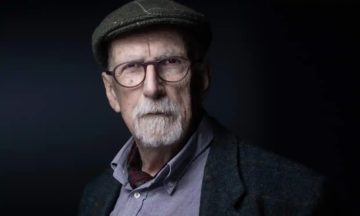

One of the most enduring ideas in economics is that free markets bring peace between countries. It comes from the notion that commerce drives humans to follow their mutual material interests rather than make destructive war due to passions. The French thinker Bruno Latour, known for his influential research on the philosophy of science has died aged 75.

The French thinker Bruno Latour, known for his influential research on the philosophy of science has died aged 75. HAVE YOU NOTICED lately that everything is shit? Things were very shitty the year before last, they became even shittier last year, and now everything is just indescribably shit. As a species, we’ve been stuck with this aspect of the human condition for around 300,000 years. But the question of how to respond to it intellectually and emotionally arises with fresh urgency in each new generation. And in the face of each fresh piece of shit. Traditionally, one role of philosophy has been to aid us in this task. Friar Lawrence advises Romeo, banished from his city and the arms of his girl, to sip “Adversity’s sweet milke, Philosophie.” However, over the past couple of centuries, with the transformation of philosophy into an academic discipline, its connection with self-help has largely been severed. The aim of Kieran Setiya’s new book Life Is Hard is to recapture philosophy’s ancient mission of “helping us find our way” in the face of life’s afflictions.

HAVE YOU NOTICED lately that everything is shit? Things were very shitty the year before last, they became even shittier last year, and now everything is just indescribably shit. As a species, we’ve been stuck with this aspect of the human condition for around 300,000 years. But the question of how to respond to it intellectually and emotionally arises with fresh urgency in each new generation. And in the face of each fresh piece of shit. Traditionally, one role of philosophy has been to aid us in this task. Friar Lawrence advises Romeo, banished from his city and the arms of his girl, to sip “Adversity’s sweet milke, Philosophie.” However, over the past couple of centuries, with the transformation of philosophy into an academic discipline, its connection with self-help has largely been severed. The aim of Kieran Setiya’s new book Life Is Hard is to recapture philosophy’s ancient mission of “helping us find our way” in the face of life’s afflictions. The girls and women of Iran are just bitchin’ brave, flipping the bird at its Supreme Leader in a challenge to one of the most significant revolutions in modern history. Day after dangerous day, on open streets and in gated schools, in a flood of tweets and brazen videos, they have ridiculed a theocracy that deems itself the government of God. The average age of the protesters who have been arrested is just fifteen, the Revolutionary Guard’s deputy commander

The girls and women of Iran are just bitchin’ brave, flipping the bird at its Supreme Leader in a challenge to one of the most significant revolutions in modern history. Day after dangerous day, on open streets and in gated schools, in a flood of tweets and brazen videos, they have ridiculed a theocracy that deems itself the government of God. The average age of the protesters who have been arrested is just fifteen, the Revolutionary Guard’s deputy commander  Fredric Jameson in Sidecar:

Fredric Jameson in Sidecar: Alden Young in Phenomenal World:

Alden Young in Phenomenal World: Blake Smith in American Affairs:

Blake Smith in American Affairs: I

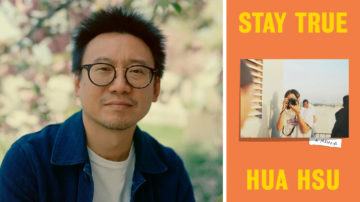

I One of the funny things about adolescence is that the world can seem enormous, brimming with possibility, while at the same time the urgency to define oneself — fastidiously curating likes and dislikes, ruthlessly sorting people according to their musical tastes — can make the world feel extremely small.

One of the funny things about adolescence is that the world can seem enormous, brimming with possibility, while at the same time the urgency to define oneself — fastidiously curating likes and dislikes, ruthlessly sorting people according to their musical tastes — can make the world feel extremely small.