Category: Recommended Reading

Saturday Poem

Call to Arms

Only you, O Iranian woman, have remained

In bonds of wretchedness, misfortune, and cruelty;

If you want these bonds broken,

grasp the skirt of obstinacy

Do not relent because of pleasing promises,

never submit to tyranny;

become a flood of anger, hate and pain,

excise the heavy stone of cruelty.

It is your warm embracing bosom

that nurtures proud and pompous man;

it is your joyous smile that bestows

on his heart warmth and vigour.

For that person who is your creation,

to enjoy preference and superiority is shameful;

woman, take action because a world

awaits and is in tune with you.

Sleeping in a dark grave is happier for you

than this abject servitude and misfortune;

where is that proud man..? Tell him

to bow his head henceforth at your threshold.

Where is that proud mane? Tell him to get up

because a woman is here rising to battle him;

her words are the truth, in which cause

she will never shed tears out of weakness.

by Forough Farrokhza

from Poetic Outlaws

Friday, October 21, 2022

Some Memories of the Life and Work of Bruno Latour (1947-2022)

Justin E. H. Smith in The Hinternet:

Down in the crypt of the basilica of Saint-Maximin-La-Sainte-Baume, in the South of France, there is an exquisitely rare object. It is a skull, behind a wall of glass, and it is described by two separate and very different labels. The one label tells you it comes from a woman in her fifties, likely born in the eastern Mediterranean in the early first century CE. The other label tells you it is the skull of Mary Magdalene. Legends of her late-life migration to Southern Gaul had already been circulating for some time when the discovery of her skeletal remains in Saint-Maximin was announced in 1279, and the basilica was subsequently built up around this gravesite. In the fourteenth century the Genoese Dominican author Jacobus de Voragine tells the full story of Mary Magdalene’s shipwreck off the coast of Marseille, and of her subsequent long career of miracle-working throughout Provence. Europe was made Christian not just by real-time conversion, but also a great deal of retroactive inscription of Biblical personages, apostles, and early Church Fathers into the ancient history of what was not yet a well-delineated cultural-geographical sphere.

Down in the crypt of the basilica of Saint-Maximin-La-Sainte-Baume, in the South of France, there is an exquisitely rare object. It is a skull, behind a wall of glass, and it is described by two separate and very different labels. The one label tells you it comes from a woman in her fifties, likely born in the eastern Mediterranean in the early first century CE. The other label tells you it is the skull of Mary Magdalene. Legends of her late-life migration to Southern Gaul had already been circulating for some time when the discovery of her skeletal remains in Saint-Maximin was announced in 1279, and the basilica was subsequently built up around this gravesite. In the fourteenth century the Genoese Dominican author Jacobus de Voragine tells the full story of Mary Magdalene’s shipwreck off the coast of Marseille, and of her subsequent long career of miracle-working throughout Provence. Europe was made Christian not just by real-time conversion, but also a great deal of retroactive inscription of Biblical personages, apostles, and early Church Fathers into the ancient history of what was not yet a well-delineated cultural-geographical sphere.

In 2017 my spouse and I were standing and looking at the skull behind the glass. I was inspecting the two labels, and thinking about the ironies of the contrasting accounts they presented, when, behind us, we heard a voice: Ah, c’est bien, ils nous donnent un choix, the voice said. We turned around, and saw that it belonged to Bruno Latour. “It’s nice, they give us a choice.”

More here.

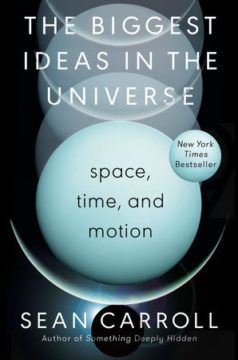

Review: “The Biggest Ideas in the Universe” by Sean Carroll

Adam Frank at Big Think:

What Carroll wants is to give readers something of the mathematical essence which, after all, is how physics is done. To accomplish this goal he proposes a novel approach. As he rightly notes, to become a practicing physicist, a student must not only learn the equations and their meanings, but they must also spend untold hours solving the equations in specific circumstances. To give an example, it is not that hard to learn the basic equations of Newtonian gravity. I walk my freshman non-science students through them. The really hard part is solving those equations for something like the motion of a comet around the Sun when it is perturbed by the gravitational pull of Jupiter. That part takes hours and hours of calculation. Learning to solve equations is what week-long graduate student homework sets are for.

What Carroll wants is to give readers something of the mathematical essence which, after all, is how physics is done. To accomplish this goal he proposes a novel approach. As he rightly notes, to become a practicing physicist, a student must not only learn the equations and their meanings, but they must also spend untold hours solving the equations in specific circumstances. To give an example, it is not that hard to learn the basic equations of Newtonian gravity. I walk my freshman non-science students through them. The really hard part is solving those equations for something like the motion of a comet around the Sun when it is perturbed by the gravitational pull of Jupiter. That part takes hours and hours of calculation. Learning to solve equations is what week-long graduate student homework sets are for.

But Carroll is betting that scientifically interested non-scientists don’t need to solve the equations of physics — they just need to know how to read them. For Carroll, understanding specifically what the specific equations say, and how they say it, should be enough to move beyond the metaphors of most popular-science accounts. In this way readers might get a more true and visceral sense of why physics is so potent.

More here.

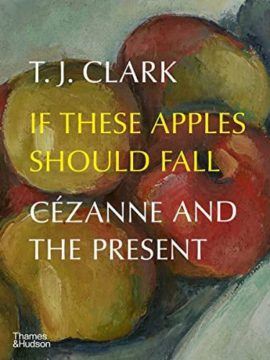

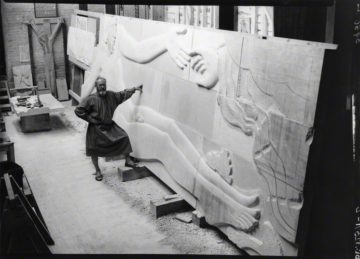

T.J. Clark’s New Book About Cézanne

Jackson Arn at Art In America:

IT TAKES A STRONG STOMACH for paradox to write that Paul Cézanne “cannot be written about any more.” When art historian T.J. Clark began a 2010 London Review of Books article on the painter this way, he meant no insult. The post-Impressionist and proto-modernist Cézanne was one of the keenest observers of the industrial disenchantment of late 19th-century Western Europe. In the 21st century, Clark argued, his paintings had become “remote to the temper of our times,” ergo, a tough subject. Accordingly, Clark’s new study of the painter, If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present, is a book about Cézanne, but also about the difficulties of writing such a book.

IT TAKES A STRONG STOMACH for paradox to write that Paul Cézanne “cannot be written about any more.” When art historian T.J. Clark began a 2010 London Review of Books article on the painter this way, he meant no insult. The post-Impressionist and proto-modernist Cézanne was one of the keenest observers of the industrial disenchantment of late 19th-century Western Europe. In the 21st century, Clark argued, his paintings had become “remote to the temper of our times,” ergo, a tough subject. Accordingly, Clark’s new study of the painter, If These Apples Should Fall: Cézanne and the Present, is a book about Cézanne, but also about the difficulties of writing such a book.

Clark accepts that Cézanne’s paintings communicate some fundamental quality of modernity, and he is willing to risk almost anything to hunt down what it was. His worry, sometimes more palpable than his overarching argument, is that Cézanne can’t be caught.

more here.

A Short History Of Panda Diplomacy

Chia-Wei Hsu at Cabinet Magazine:

Giant pandas are found in the wild only in a few mountain ranges in China, primarily in Sichuan province, which means that China controls the supply of one of the world’s most beloved animals. Pandas became a key component of China’s diplomatic relations beginning in the mid-twentieth century, with the first instance of such “panda diplomacy”—as the practice of offering the bears as the highest official gift came to be called—occurring in 1941 when Madame Chiang Kai-shek and her sister gave a pair of pandas to the United States in gratitude for assisting the country in its war with Japan. This began a tradition that continued through the Cold War to the present day, with the animal playing a vital role in China’s relationship with countries including Taiwan, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In 1936, the first living panda arrived in the West. It was brought to the United States illegally by Ruth Elizabeth Harkness, a fashion designer from New York whose husband, William, had died that February in Shanghai while preparing an expedition to capture pandas in Sichuan.

Giant pandas are found in the wild only in a few mountain ranges in China, primarily in Sichuan province, which means that China controls the supply of one of the world’s most beloved animals. Pandas became a key component of China’s diplomatic relations beginning in the mid-twentieth century, with the first instance of such “panda diplomacy”—as the practice of offering the bears as the highest official gift came to be called—occurring in 1941 when Madame Chiang Kai-shek and her sister gave a pair of pandas to the United States in gratitude for assisting the country in its war with Japan. This began a tradition that continued through the Cold War to the present day, with the animal playing a vital role in China’s relationship with countries including Taiwan, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In 1936, the first living panda arrived in the West. It was brought to the United States illegally by Ruth Elizabeth Harkness, a fashion designer from New York whose husband, William, had died that February in Shanghai while preparing an expedition to capture pandas in Sichuan.

more here.

The markets have taken back control: so much for Truss’s Brexit delusion of sovereignty

Jonathan Freedland in The Guardian:

Historians will look back and see a point of origin to the current madness, one that explains how a new prime minister could see her administration fall apart in a matter of weeks, even if we struggle to name that cause out loud right now. When the textbooks of the future come to the chapter we are living through, in the autumn of 2022, they will start with the summer of 2016: Brexit and the specific delusion that drove it.

Historians will look back and see a point of origin to the current madness, one that explains how a new prime minister could see her administration fall apart in a matter of weeks, even if we struggle to name that cause out loud right now. When the textbooks of the future come to the chapter we are living through, in the autumn of 2022, they will start with the summer of 2016: Brexit and the specific delusion that drove it.

More here.

Freeman Dyson: Why It’s Best Not to Win the Nobel Prize

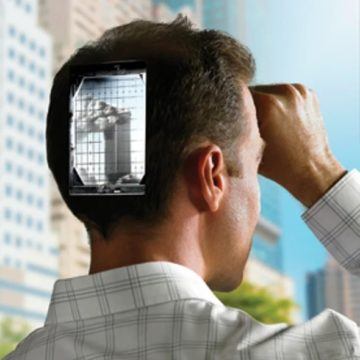

Emotion Selectively Distorts Our Recollections

Ingfei Chen in Scientific American: (From 2012)

Amid the endless stream of everyday experience, emotion is like a blazing neon tag that alerts the brain, “Yoo-hoo, this is a moment worth remembering!” The salience of the humdrum sandwich you ate for lunch pales in comparison, consigning its memory to the dustbin. Yet emotions regulate our recall of not just our most riveting moments. Researchers now recognize that the same neural mechanisms involved in flashbulb memories underlie recollections along the continuum of human emotional experience. When people view a series of pictures or words in the laboratory, any emotionally laden content sticks in their head better than neutral information.

Amid the endless stream of everyday experience, emotion is like a blazing neon tag that alerts the brain, “Yoo-hoo, this is a moment worth remembering!” The salience of the humdrum sandwich you ate for lunch pales in comparison, consigning its memory to the dustbin. Yet emotions regulate our recall of not just our most riveting moments. Researchers now recognize that the same neural mechanisms involved in flashbulb memories underlie recollections along the continuum of human emotional experience. When people view a series of pictures or words in the laboratory, any emotionally laden content sticks in their head better than neutral information.

Memory is a three-stage process: First comes the learning or encoding of an experience; then, the storage or consolidation of that information over many hours, days and months; and last, the retrieval of that memory when you later relive it. Insights into how emotion modulates this process emerged from studies of conditioned fear responses in rats in the 1980s and 1990s by neuroscientists Joseph E. LeDoux, now at N.Y.U. [see “Mastery of Emotions,” by David Dobbs; Scientific American Mind, February/March 2006], and James L. McGaugh of the University of California, Irvine, among others. Their work established that the amygdala, a structure buried deep within the brain, orchestrates the memory-boosting effects of fear.

More here. (Note: Reading Proust these days has reignited my interest in memories. We know shockingly little about the science)

The best way to lower your dementia risk

Tara Parker-Pope in The Washington Post:

Why the Brain Loves Music, Dr. Oliver Sacks

Friday Poem

Talk

The body is never silent. Aristotle said that we

can’t hear the music of the spheres because it is the

first thing that we hear, blood at the ear. Also the

body is brewing its fluids. It is braiding the rope of

food that moors us to the dead. Because it sniffles

and farts, we love the unpredictable. Because

breath goes in and out, there are two of each of us

and they distrust each other. The body’s reassuring

slurps and creaks are like a dial tone: we can

call up the universe. And so we are always

talking. My body and I sit up late, telling each other

our troubles. And when two bodies are near each

other, they begin talking in body-sonar. The art of

conversation is not dead! Still, for long periods, it is

comatose. For example, suppose my body doesn’t

get near enough to yours for a long time. It is dis-

consolate. Normally it talks to me all night: listening

is how I sleep. Now it is truculent. It wants to speak

directly to your body. The next voice to hear will

be my body’s. It sounds the same way blood sounds

at your ear. It is saying Ssshhh, now that we, at

last, are silent.

by William Matthews

from Sleek for the Long Flight

White Pine Press, 1988

Thursday, October 20, 2022

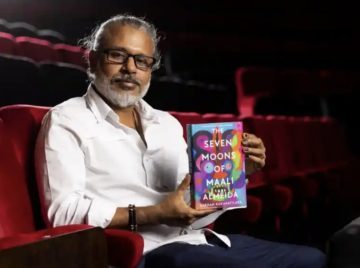

Shehan Karunatilaka wins Booker prize for The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida

Sarah Shaffi and Lucy Knight in The Guardian:

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka has won the Booker prize for fiction. The judges praised the “ambition of its scope, and the hilarious audacity of its narrative techniques”.

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka has won the Booker prize for fiction. The judges praised the “ambition of its scope, and the hilarious audacity of its narrative techniques”.

Karunatilaka’s second novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida comes more than a decade after his debut, Chinaman, which was published in 2011. The Booker-winning novel tells the story of the photographer of its title, who in 1990 wakes up dead in what seems like a celestial visa office. With no idea who killed him, Maali has seven moons to contact the people he loves most and lead them to a hidden cache of photos of civil war atrocities that will rock Sri Lanka.

Neil MacGregor, chair of the judges for this year’s prize, said the novel was chosen because “it’s a book that takes the reader on a rollercoaster journey through life and death right to what the author describes as the dark heart of the world”.

More here.

Self-Taught AI Shows Similarities to How the Brain Works

Anil Ananthaswamy in Quanta:

Now some computational neuroscientists have begun to explore neural networks that have been trained with little or no human-labeled data. These “self-supervised learning” algorithms have proved enormously successful at modeling human language and, more recently, image recognition. In recent work, computational models of the mammalian visual and auditory systems built using self-supervised learning models have shown a closer correspondence to brain function than their supervised-learning counterparts. To some neuroscientists, it seems as if the artificial networks are beginning to reveal some of the actual methods our brains use to learn.

Now some computational neuroscientists have begun to explore neural networks that have been trained with little or no human-labeled data. These “self-supervised learning” algorithms have proved enormously successful at modeling human language and, more recently, image recognition. In recent work, computational models of the mammalian visual and auditory systems built using self-supervised learning models have shown a closer correspondence to brain function than their supervised-learning counterparts. To some neuroscientists, it seems as if the artificial networks are beginning to reveal some of the actual methods our brains use to learn.

More here.

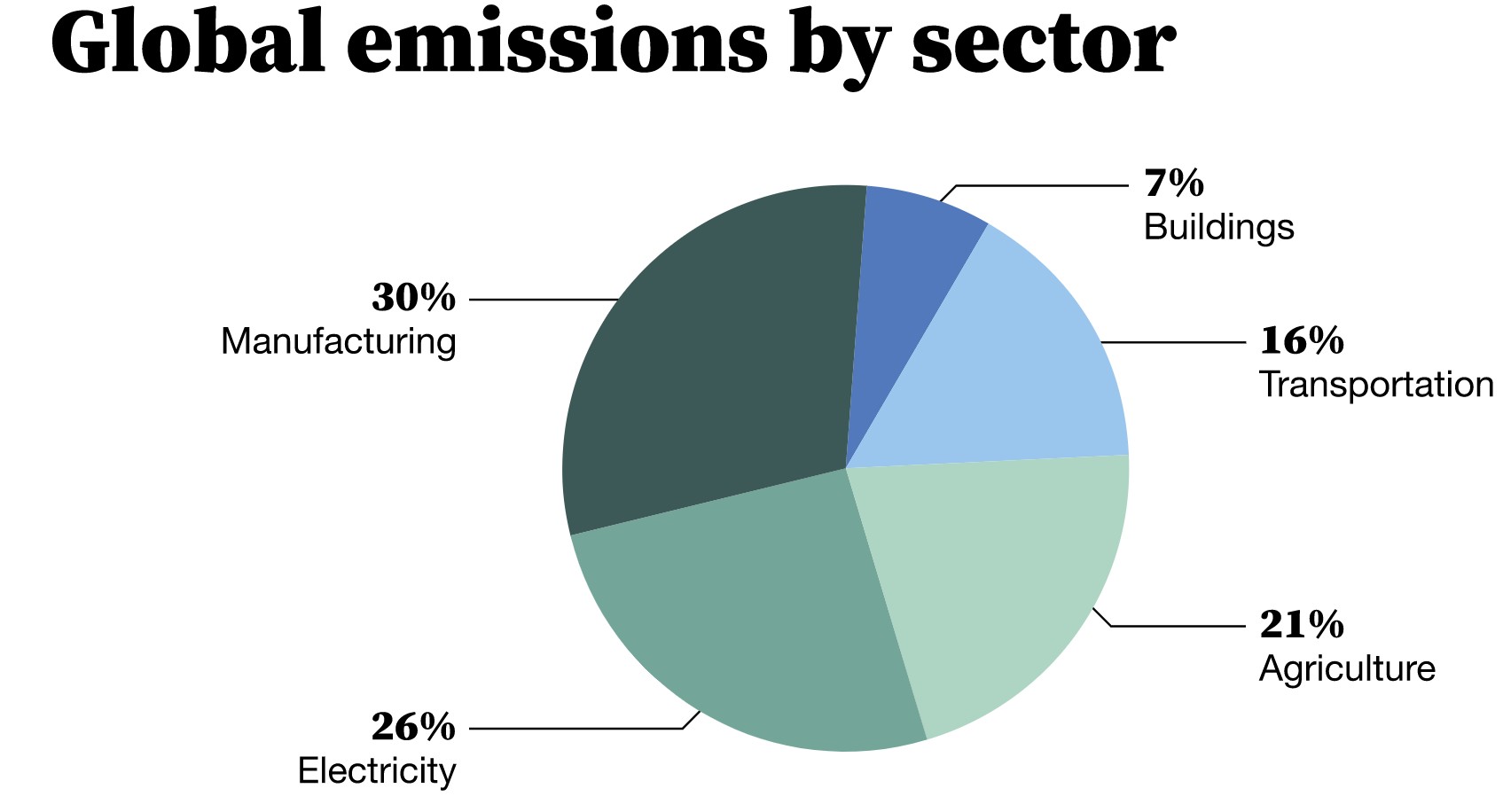

Bill Gates: How we’re doing on the path to zero emissions

Bill Gates’s annual memo about the journey to zero emissions

Bill Gates in his blog, Gates Notes:

When I first started learning about climate change 15 years ago, I came to three conclusions. First, avoiding a climate disaster would be the hardest challenge people had ever faced. Second, the only way to do it was to invest aggressively in clean-energy innovation and deployment. And third, we needed to get going.

When I first started learning about climate change 15 years ago, I came to three conclusions. First, avoiding a climate disaster would be the hardest challenge people had ever faced. Second, the only way to do it was to invest aggressively in clean-energy innovation and deployment. And third, we needed to get going.

Since then, an influx of private and public investment has accelerated innovation faster than I dared hope. This progress makes me optimistic about the future.

But I am also realistic about the present. The world still needs to reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions from 51 billion tons to zero, but global emissions continue to increase every year. If you follow the annual IPCC reports, you’ve watched as the scenarios for limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 or even 2 degrees Celsius become increasingly remote. And some of the clean technologies we need are still very far from becoming practical, cost-effective solutions we can deploy at scale.

More here.

What The Rosetta Stone Actually Says

When the Push Button Was New, People Were Freaked

Matthew Wills at JSTOR Daily:

The doorbell. The intercom. The elevator. Once upon a time, beginning in the late nineteenth century, pushing the button that activated such devices was a strange new experience. The electric push button, the now mundane-seeming interface between human and machine, was originally a spark for wonder, anxiety, and social transformation.

As media studies scholar Rachel Plotnick details, people worried that the electric push button would make human skills atrophy. They wondered if such devices would seal off the wonders of technology into a black box: “effortless, opaque, and therefore unquestioned by consumers.” Today, you’d probably have to schedule an electrician to fix what some children back then knew how to make: electric bells, buttons, and buzzers.

more here.

The Meaning Of Classicism

Amit Chaudhuri at n+1:

OVER A DECADE AGO, I began to inadvertently call my mother’s singing “classicist.” I say “inadvertently” because I think I was, without fully realizing it, using the word in Eliot’s sense. My mother, Bijoya Chaudhuri, was a singer of Tagore songs—largely ignored, but admired by a few for being one of the great singers of her generation. In using “classicist,” I may have meant to connect her style to North Indian classical music. And North Indian classical music is “classicist” in the way Eliot, I believe, uses the word: vocal music in this tradition preoccupies itself with the expression of the note, of the raga, but not with emotion in the conventional humanist sense—that is, not with self-expression. One of the ways it does this is by eschewing vibrato and tremolo, which became such an effective means of bringing emotional drama to opera in the Romantic period. However intricate the embellishments in North Indian classical vocal music (and they are the most complex and difficult in any vocal tradition), they must return repeatedly to the stillness (thheherao) and purity of the note. One of the ways this happens is through the ah sound that dominates North Indian classical vocal music.

OVER A DECADE AGO, I began to inadvertently call my mother’s singing “classicist.” I say “inadvertently” because I think I was, without fully realizing it, using the word in Eliot’s sense. My mother, Bijoya Chaudhuri, was a singer of Tagore songs—largely ignored, but admired by a few for being one of the great singers of her generation. In using “classicist,” I may have meant to connect her style to North Indian classical music. And North Indian classical music is “classicist” in the way Eliot, I believe, uses the word: vocal music in this tradition preoccupies itself with the expression of the note, of the raga, but not with emotion in the conventional humanist sense—that is, not with self-expression. One of the ways it does this is by eschewing vibrato and tremolo, which became such an effective means of bringing emotional drama to opera in the Romantic period. However intricate the embellishments in North Indian classical vocal music (and they are the most complex and difficult in any vocal tradition), they must return repeatedly to the stillness (thheherao) and purity of the note. One of the ways this happens is through the ah sound that dominates North Indian classical vocal music.

more here.

Thursday Poem

The Such Thing As the Ridiculous Question –

Where are you from???

When I say ancestors, let’s be clear:

I mean slaves. I’m talkin’ Tennessee

cotton & Louisiana suga. I mean grave

dirt. I come from homes & marriages

named after the same type of weapon –

all it takes is a shotgun to know

I’m Black. I don’t got no secrets

a bullet ain’t told. Danger see me

& sit down somewhere.

I’m a direct descendant of last words

& first punches. I got stolen blood.

My complexion is America’s

darkest hour. You can trace my great

great great great great grandmother back

to a scream. I bet somewhere it’s a haint

with my eyes. My last name is a protest;

a brick through a window in a house

my bones built. One million

scabs from one scar.

Heavy is the hand that held

the whip. Black is the back that carried this

country & when this country’s palm gets

an itch, I become money. You give this country

an inch & it will take a freedom. You can’t talk slick

to this legacy of oiled scalps. You can’t spit

on my race & call it reign. I sound like my mama now,

who sound like her mama who sound like her mama who

sound like her mama, who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama, who sound like a scream.

& that’s why I’m so loud, remember? You wanna know

where I’m from? Easy. Open a wound

& watch it heal.

by Siaara Freeman

from Split This Rock

Listen to reading: here

There are many good reasons to take care of your hearing — from the sound of birds chirping to being able to carry on a conversation in a restaurant. But the best reason to take care of your hearing is to take care of your brain. Hearing loss in middle age — ages 45 to 65 — is the most significant risk factor for dementia, accounting for more than 8 percent of all dementia cases, Richard Sima reports in this week’s

There are many good reasons to take care of your hearing — from the sound of birds chirping to being able to carry on a conversation in a restaurant. But the best reason to take care of your hearing is to take care of your brain. Hearing loss in middle age — ages 45 to 65 — is the most significant risk factor for dementia, accounting for more than 8 percent of all dementia cases, Richard Sima reports in this week’s