Henry Cowles in LARB:

When the blackbird flew out of sight,

When the blackbird flew out of sight,

It marked the edge

Of one of many circles.

BLACKBIRDS AREN’T ALL BLACK. They can be red-winged or red-shouldered, saffron-cowled or tricolored, rusty or yellow-hooded or chestnut-capped. And that’s just the members of the family Icteridae called blackbirds. Orioles and grackles, with their oranges and iridescence, are part of the family too. Old World blackbirds, many of which are called thrushes, are only distantly related; black birds like ravens and most crows aren’t blackbirds at all. To me, this fuzziness is part of the joke of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” a poem by Wallace Stevens first published in 1917. Across the poem’s 13 cantos, birds whirl and whistle, cast their shadows or eye us from the trees. Whether or not they’re all blackbirds — and, if so, what kind, with what colors? — the singular “a” of Stevens’s title is clearly misdirection. There are as many birds as there are perspectives, if not more, and as ever, what is true of the poem is true of the world. The more ways we look, the more we realize how much there is to see. Glance by glance, the blackbirds multiply.

Think about anything often enough, from enough angles, and it’s bound to splinter and refract. Our minds are like kaleidoscopes, packed with mirrors we twist to see the world anew. Sometimes we’re twisting consciously, sometimes unconsciously. But no matter what, we end up seeing patterns that are more a product of the tool in hand than of the world on its other end. Stevens’s poem, on this reading, is less about blackbirds than about the lenses we use to spy on them. It’s a warning, in other words, not to mistake the kaleidoscope for the universe.

More here.

Scientists have successfully transplanted clusters of human neurons into the brains of newborn rats, a striking feat of biological engineering that may provide more realistic models for neurological conditions such as autism and serve as a way to restore injured brains.

Scientists have successfully transplanted clusters of human neurons into the brains of newborn rats, a striking feat of biological engineering that may provide more realistic models for neurological conditions such as autism and serve as a way to restore injured brains. In the US, we are feeling the sickening after-effects of

In the US, we are feeling the sickening after-effects of  Actually, until 1961, when I was 16, I’d never given any thought to Sweden at all, but everything shifted on a dime when my Dad shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. That December, our family flew to Stockholm for the ceremonies and it was unforgettable. Not only were the solemn, yet deeply joyous, festivities a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, but I was powerfully struck by the classic European beauty of Stockholm in the midst of that romantically dark and snowy Scandinavian winter—such a clean and sophisticated city with its old-fashioned trams, its glittering neon signs, its colorful store windows, its elegant ladies and gentlemen, and, last but not least, its strange, alien language.

Actually, until 1961, when I was 16, I’d never given any thought to Sweden at all, but everything shifted on a dime when my Dad shared the 1961 Nobel Prize in Physics. That December, our family flew to Stockholm for the ceremonies and it was unforgettable. Not only were the solemn, yet deeply joyous, festivities a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, but I was powerfully struck by the classic European beauty of Stockholm in the midst of that romantically dark and snowy Scandinavian winter—such a clean and sophisticated city with its old-fashioned trams, its glittering neon signs, its colorful store windows, its elegant ladies and gentlemen, and, last but not least, its strange, alien language. In 1977, Ken Olsen declared that ‘there is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.’ In 1995, Robert Metcalfe predicted in InfoWorld that the internet would go ‘spectacularly supernova’ and then collapse within a year. In 2000, the Daily Mail reported that the ‘Internet may be just a passing fad,’ adding that ‘predictions that the Internet would revolutionise the way society works have proved wildly inaccurate.’ Any day now, the millions of internet users would simply stop, either bored or frustrated, and rejoin the real world.

In 1977, Ken Olsen declared that ‘there is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home.’ In 1995, Robert Metcalfe predicted in InfoWorld that the internet would go ‘spectacularly supernova’ and then collapse within a year. In 2000, the Daily Mail reported that the ‘Internet may be just a passing fad,’ adding that ‘predictions that the Internet would revolutionise the way society works have proved wildly inaccurate.’ Any day now, the millions of internet users would simply stop, either bored or frustrated, and rejoin the real world. Nobel Prizes used to be awarded fairly quickly after the discovery, achievement, or event that prompted them. The instructions left by Alfred Nobel seemed to warrant this speed. However, this has occasionally led to awards for discoveries that later turned out to be bunk. Perhaps no case of this is clearer-cut than the 1926 prize in medicine, which was awarded “for [Fibiger’s] discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma.”

Nobel Prizes used to be awarded fairly quickly after the discovery, achievement, or event that prompted them. The instructions left by Alfred Nobel seemed to warrant this speed. However, this has occasionally led to awards for discoveries that later turned out to be bunk. Perhaps no case of this is clearer-cut than the 1926 prize in medicine, which was awarded “for [Fibiger’s] discovery of the Spiroptera carcinoma.” The House committee tasked with investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol made its closing arguments to the American public today and voted 9-0 to subpoena former President Donald Trump. They highlighted snippets from more than a million Secret Service communications in the days and hours leading up to the breach of the Capitol, bolstering their thesis that then-President Donald Trump had incited a mob and bears singular responsibility for the violence that ensued. “Armed and Ready, Mr. President!” read one snippet of intelligence presented in a Secret Service email on Dec. 24, 2020, about two weeks before the Jan. 6 joint session of Congress to formalize Joe Biden’s election victory.

The House committee tasked with investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol made its closing arguments to the American public today and voted 9-0 to subpoena former President Donald Trump. They highlighted snippets from more than a million Secret Service communications in the days and hours leading up to the breach of the Capitol, bolstering their thesis that then-President Donald Trump had incited a mob and bears singular responsibility for the violence that ensued. “Armed and Ready, Mr. President!” read one snippet of intelligence presented in a Secret Service email on Dec. 24, 2020, about two weeks before the Jan. 6 joint session of Congress to formalize Joe Biden’s election victory. Pain has been long recognized as one of evolution’s most reliable tools to detect the presence of harm and signal that something is wrong—an alert system that tells us to pause and pay attention to our bodies. But what if

Pain has been long recognized as one of evolution’s most reliable tools to detect the presence of harm and signal that something is wrong—an alert system that tells us to pause and pay attention to our bodies. But what if  Cihan Tugal in Sidecar:

Cihan Tugal in Sidecar: Samir Sonti and JW Mason in Phenomenal World:

Samir Sonti and JW Mason in Phenomenal World: Ingrid Robeyns in Crooked Timber:

Ingrid Robeyns in Crooked Timber: This is a song that does no favors for anyone, and casts doubt on everything.

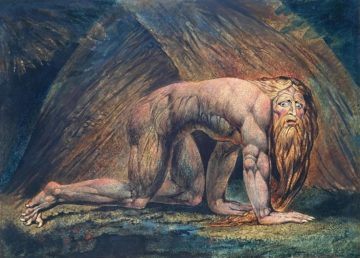

This is a song that does no favors for anyone, and casts doubt on everything. In June 1794,

In June 1794,