Ronald Collins in The Washington Post:

In early September 1957, Jack Kerouac achieved the dream of every writer. Around midnight he and his girlfriend, Joyce Glassman, left her brownstone apartment in New York City for a nearby newsstand at Broadway and 66th Street. They waited while the nightman cut the twine around the morning edition of the New York Times. Rifling through the paper, they found on Page 27 an expected review of Kerouac’s new book, “On the Road.”

In early September 1957, Jack Kerouac achieved the dream of every writer. Around midnight he and his girlfriend, Joyce Glassman, left her brownstone apartment in New York City for a nearby newsstand at Broadway and 66th Street. They waited while the nightman cut the twine around the morning edition of the New York Times. Rifling through the paper, they found on Page 27 an expected review of Kerouac’s new book, “On the Road.”

Glassman recalled that she “felt dizzy reading the first paragraph.”

Kerouac was reading along, too. “It’s good, isn’t it?” he asked.

“Yes, it’s very, very good,” Glassman recounted in her 1983 memoir.

That breakthrough review, written by Gilbert Millstein in the “Books of the Times” column, changed the course of literary history and the career of Kerouac, who died 50 years ago this fall, on Oct. 21, 1969. If not for that review, Kerouac might have remained a minor writer and the Beat Generation so fully associated with his name may never have flourished as it did. After all, seven years earlier, Kerouac had published his first book, “The Town and the City,” to modest reviews, which were not enough to propel him to fame.

With the first line of his critique of “On the Road,” Millstein announced a work of transcendent proportions. “Its publication is a historic occasion,” he proclaimed. In the piece, he probed the depths of Kerouac the writer and explored the breadth of “On the Road.” Millstein billed the pseudo-philosophic road novel as an “authentic work of art.” After examining the sociological and psychological dimensions of the book, he rhapsodized over its style, declaring, “The writing is of a beauty almost breathtaking.” And he quoted what would become the canonical lines from the novel: “The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles.”

More here.

In their controversial 2013 opus The Undercommons, radicals Fred Moten and Stefano Harney detail the eponymous academic-activist ferment to which they owe their radicality. The undercommons is located in the university—more generally, in the swarm of relations and systems we could call “academia” or “intellectual life”—but is not a physical place; rather, it is a “downlow lowdown maroon community of the university … where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still black, still strong.”

In their controversial 2013 opus The Undercommons, radicals Fred Moten and Stefano Harney detail the eponymous academic-activist ferment to which they owe their radicality. The undercommons is located in the university—more generally, in the swarm of relations and systems we could call “academia” or “intellectual life”—but is not a physical place; rather, it is a “downlow lowdown maroon community of the university … where the work gets done, where the work gets subverted, where the revolution is still black, still strong.” Of most interest to us, the readers of Eliot’s poetry, is the writing of verse for which he somehow found the time and energy. The early drama in Crawford’s account is Eliot’s composition of “The Hollow Men” and “Ash Wednesday” out of his struggles with the frailty of the body (exemplified in Vivien’s constant and severe intestinal illness and his own frequent bouts of flu and bronchitis) and the soul (tormented by shame over the body’s needs and failures, including the repeated fall into sexual guilt). Tormented, Eliot turned to an array of cultural resources. While Baudelaire and Dante continued to inform his thinking, they were joined now by an increasing interest in the theatre, especially the non-naturalistic modes available in puppetry, ballet, and mechanistic work. The poetry of other languages and the suspension of access to meaning entailed in the act of translation helped him to incorporate estrangement into his own poems; Eliot’s labor on a translation of Saint-John Perse’s Anabasis shaped the lines and phrases of his work of the mid-1920s. But the cultural resources Eliot brought to the processing of pain were not limited to the literary.

Of most interest to us, the readers of Eliot’s poetry, is the writing of verse for which he somehow found the time and energy. The early drama in Crawford’s account is Eliot’s composition of “The Hollow Men” and “Ash Wednesday” out of his struggles with the frailty of the body (exemplified in Vivien’s constant and severe intestinal illness and his own frequent bouts of flu and bronchitis) and the soul (tormented by shame over the body’s needs and failures, including the repeated fall into sexual guilt). Tormented, Eliot turned to an array of cultural resources. While Baudelaire and Dante continued to inform his thinking, they were joined now by an increasing interest in the theatre, especially the non-naturalistic modes available in puppetry, ballet, and mechanistic work. The poetry of other languages and the suspension of access to meaning entailed in the act of translation helped him to incorporate estrangement into his own poems; Eliot’s labor on a translation of Saint-John Perse’s Anabasis shaped the lines and phrases of his work of the mid-1920s. But the cultural resources Eliot brought to the processing of pain were not limited to the literary. Cambodian American Eden Teng was was born in a refugee camp on the border of Thailand and Cambodia just a few years after the Cambodian genocide. She moved to the U.S. with her mom and aunt when she was 6. Teng attributes much of her own resilience in transitioning to the U.S. to her exuberant mom, who wore whatever she wanted and wasn’t afraid to defy social norms — even when it was embarrassing for a teenage Teng.

Cambodian American Eden Teng was was born in a refugee camp on the border of Thailand and Cambodia just a few years after the Cambodian genocide. She moved to the U.S. with her mom and aunt when she was 6. Teng attributes much of her own resilience in transitioning to the U.S. to her exuberant mom, who wore whatever she wanted and wasn’t afraid to defy social norms — even when it was embarrassing for a teenage Teng. Political strategists on winning campaigns are visited like gurus after an election, with reporters looking to discern secrets of success that might be replicated at scale. In this spirit, in the days after the midterms, the

Political strategists on winning campaigns are visited like gurus after an election, with reporters looking to discern secrets of success that might be replicated at scale. In this spirit, in the days after the midterms, the  IF ’80S CINEMA experienced a “

IF ’80S CINEMA experienced a “ The digital era has two basic axioms. The first is that information has no form; information technology is a means of disseminating and aggregating data, but data itself belongs to no place or context. Data cannot tell the story; information is uninforming and uninformative. The digital age can therefore have no real culture of its own, no culture in the etymological sense of cultivation and accumulated growth. Things trend or happen online, but nothing settles into lasting place or takes its time to show itself significant. Each day’s frenzy and distraction are as overwhelming unto the day as they are forgettable.

The digital era has two basic axioms. The first is that information has no form; information technology is a means of disseminating and aggregating data, but data itself belongs to no place or context. Data cannot tell the story; information is uninforming and uninformative. The digital age can therefore have no real culture of its own, no culture in the etymological sense of cultivation and accumulated growth. Things trend or happen online, but nothing settles into lasting place or takes its time to show itself significant. Each day’s frenzy and distraction are as overwhelming unto the day as they are forgettable. The second axiom is that the Internet is for cat pictures; everyone knows that transmitting images of cute animals is the whole point of it. It remains astounding that pet videos run into the tens of millions of views. That they have their own film festival. That they are used as bait to pull people into political misinformation campaigns. That there are bona fide pet celebrities and pet influencers. That some of them are raking it in, with spin-off merch and copyrighted brand clout all their own.

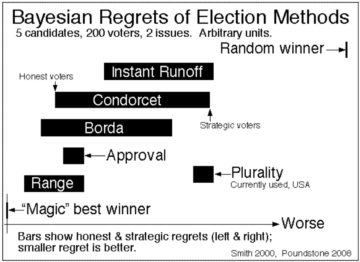

The second axiom is that the Internet is for cat pictures; everyone knows that transmitting images of cute animals is the whole point of it. It remains astounding that pet videos run into the tens of millions of views. That they have their own film festival. That they are used as bait to pull people into political misinformation campaigns. That there are bona fide pet celebrities and pet influencers. That some of them are raking it in, with spin-off merch and copyrighted brand clout all their own. Here is the setup. You have a set of voters {1, 2, 3, …} and a set of choices {A, B, C, …}. The choices may be candidates for office, but they may equally well be where a group of friends is going to meet for dinner; it doesn’t matter. Each voter has a ranking of the choices, from most favorite to least, so that for example voter 1 might rank D first, A second, C third, and so on. We will ignore the possibility of ties or indifference concerning certain choices, but they’re not hard to include. What we don’t include is any measure of intensity of feeling: we know that a certain voter prefers A to B and B to C, but we don’t know whether (for example) they could live with B but hate C with a burning passion. As

Here is the setup. You have a set of voters {1, 2, 3, …} and a set of choices {A, B, C, …}. The choices may be candidates for office, but they may equally well be where a group of friends is going to meet for dinner; it doesn’t matter. Each voter has a ranking of the choices, from most favorite to least, so that for example voter 1 might rank D first, A second, C third, and so on. We will ignore the possibility of ties or indifference concerning certain choices, but they’re not hard to include. What we don’t include is any measure of intensity of feeling: we know that a certain voter prefers A to B and B to C, but we don’t know whether (for example) they could live with B but hate C with a burning passion. As  Now that the American electorate appears to have rejected Republican extremism, some will argue that Biden should tack right to capture the political center. But that is the wrong way to read the 2022 midterm result, because the electorate is not seeking some kind of Solomonic splitting of the baby.

Now that the American electorate appears to have rejected Republican extremism, some will argue that Biden should tack right to capture the political center. But that is the wrong way to read the 2022 midterm result, because the electorate is not seeking some kind of Solomonic splitting of the baby. The Liz Truss

The Liz Truss  Bacterial infections are the second leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for one in eight of all deaths in 2019, the first global estimate of their lethality revealed on Tuesday.

Bacterial infections are the second leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for one in eight of all deaths in 2019, the first global estimate of their lethality revealed on Tuesday. Your classiest friend invites you to dinner. They take out a bottle of Chardonnay that costs more than your last vacation and pour each of you a drink. They sip from their glass. “Ah,” they say. “1973. An excellent vintage. Notes of avocado, gingko and strontium.” You’re not sure what to do. You mumble something about how you can really taste the strontium. But internally, you wonder: Is wine fake?

Your classiest friend invites you to dinner. They take out a bottle of Chardonnay that costs more than your last vacation and pour each of you a drink. They sip from their glass. “Ah,” they say. “1973. An excellent vintage. Notes of avocado, gingko and strontium.” You’re not sure what to do. You mumble something about how you can really taste the strontium. But internally, you wonder: Is wine fake? For most of my adult life, I believed in the implications of the phrase “non-stick pans”: other pans must be unmanageably sticky. During the pandemic, as I began to want my own listening room and wrote every day across from a stove, I started to cook. I bought a Lodge cast-iron skillet that cost about forty dollars. It heats up quickly and evenly and can be easily cleaned. Our non-stick pan, by comparison, sheds its coating, and the handle keeps coming unscrewed. This is like the history of audio gear. The cast iron was sufficient, but an imaginary quality—stickiness—was being “solved” by new technology like Teflon. The new gear is fine, and works well in a couple of settings, but seems largely like an unnecessary innovation.

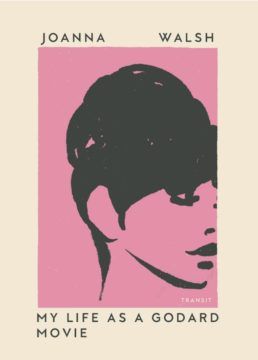

For most of my adult life, I believed in the implications of the phrase “non-stick pans”: other pans must be unmanageably sticky. During the pandemic, as I began to want my own listening room and wrote every day across from a stove, I started to cook. I bought a Lodge cast-iron skillet that cost about forty dollars. It heats up quickly and evenly and can be easily cleaned. Our non-stick pan, by comparison, sheds its coating, and the handle keeps coming unscrewed. This is like the history of audio gear. The cast iron was sufficient, but an imaginary quality—stickiness—was being “solved” by new technology like Teflon. The new gear is fine, and works well in a couple of settings, but seems largely like an unnecessary innovation. In My Life, Walsh remembers a time when “instead of dying I went to Paris,” a providentially budgeted eleventh-hour day trip consisting of “ten hours’ travel and eight hours’ walking: eighteen hours: a day, a day that saved my life.” The transformation by the pandemic of Paris — of crowds, of urban bustle, of the tactile delectations of flânerie — from a font of salvation into a space of mortal dangers and morbid anxieties appears as a kind of violent inversion. But this alienated affect sits comfortably in Walsh’s oeuvre: the founding condition of her writings is a consciousness and interrogation of feelings of geographic, interpersonal, and emotional displacement. Her women navigate their worlds in the exilic mode. Walsh’s settings are intermediary or quite literally transit/ory: hers is a literature of the cafe, the train, the bus, the hotel. That the principal concerns of Godard’s early period were the ennui and political uncertainties of an interstitial generation (“the children of Marx and Coca-Cola,” as Godard notoriously identifies them in 1966’s Masculin Féminin), the defamiliarization of romance, and a kind of uncanny French apocalyptica (think, for example, of the remarkable, and remarkably long, single-take traffic scene in Week-end) establishes an especially fructuous ground for Walsh’s philosophies of the uprooted.

In My Life, Walsh remembers a time when “instead of dying I went to Paris,” a providentially budgeted eleventh-hour day trip consisting of “ten hours’ travel and eight hours’ walking: eighteen hours: a day, a day that saved my life.” The transformation by the pandemic of Paris — of crowds, of urban bustle, of the tactile delectations of flânerie — from a font of salvation into a space of mortal dangers and morbid anxieties appears as a kind of violent inversion. But this alienated affect sits comfortably in Walsh’s oeuvre: the founding condition of her writings is a consciousness and interrogation of feelings of geographic, interpersonal, and emotional displacement. Her women navigate their worlds in the exilic mode. Walsh’s settings are intermediary or quite literally transit/ory: hers is a literature of the cafe, the train, the bus, the hotel. That the principal concerns of Godard’s early period were the ennui and political uncertainties of an interstitial generation (“the children of Marx and Coca-Cola,” as Godard notoriously identifies them in 1966’s Masculin Féminin), the defamiliarization of romance, and a kind of uncanny French apocalyptica (think, for example, of the remarkable, and remarkably long, single-take traffic scene in Week-end) establishes an especially fructuous ground for Walsh’s philosophies of the uprooted.