Daniela Gabor and Ndongo Samba Sylla in Boston Review:

Daniela Gabor and Ndongo Samba Sylla in Boston Review:

Few remember Cheikh Anta Diop—the renowned Senegalese historian and Pan-African political leader—as an early prophet of climate change. Yet we should. Writing in 1985, as the world debated an oil glut that was pushing prices to historic lows, Diop envisioned a green Pan-African future. “Powered by hydrogen,” he wrote, “a supersonic plane would only dump tons of water into the atmosphere, whereas one powered by kerosene pollutes in three minutes what the Fontainebleau forest takes a day to absorb.” Imagine, Diop invited his audience, “a university and an African government putting in place, in five years, a small solar plant, somewhere close to the sea, that would produce renewable energy to split seawater into hydrogen and oxygen, and then experiment with liquifying, storage, transport, and other pilot projects.” Green hydrogen, he believed, could build on Africa’s abundant renewable resources.

Diop hoped that developmental states intent on industrialization would coordinate and ultimately unite politically to create the continent’s green hydrogen revolution. Refusing (neo)colonial tropes of “catching up” Africa, the historian versed in chemistry and physics urged African governments to nurture the local capabilities that would pioneer world-leading green hydrogen technologies and build green industries. He described a future where the continent shared these technologies with the rest of the world, one that broke with centuries of colonial—and then neocolonial—extraction. Diop wanted Africa to export green hydrogen technology rather than hydrogen commodities vulnerable to price volatility and neocolonial extractivism.

More here.

Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World:

Herman Mark Schwartz in Phenomenal World: Cormac McCarthy had provided me with a context, even a language, to internalize the things I saw and cannot unsee. Segments of human beings were stacked along the road between the smoking-bombed-out war machines.

Cormac McCarthy had provided me with a context, even a language, to internalize the things I saw and cannot unsee. Segments of human beings were stacked along the road between the smoking-bombed-out war machines. C

C

HUNTSVILLE, Ala. — It was an unusually chilly Thursday night in December, and a drag queen named Miss Majesty Divine was putting the final touches on her show makeup. She was about to go onstage for her regular gig at a basement tiki bar, one of the last performances before Christmas. Up at street level, two unwelcome guests had arrived. They were not fans. They were men with bushy beards, one holding a bullhorn, the other a placard that depicted a drag queen holding a screaming baby and the hashtag #stopdragqueenstoryhour. “Repent, you filthy dog! You are going to burn in hell!” the one with the bullhorn shouted. “God sent AIDS to deal with people like you!” Madge, as she is known to her friends and adoring fans, was unfazed. “I teach math to middle schoolers,” Madge deadpanned. “You think I haven’t been called some things?”

HUNTSVILLE, Ala. — It was an unusually chilly Thursday night in December, and a drag queen named Miss Majesty Divine was putting the final touches on her show makeup. She was about to go onstage for her regular gig at a basement tiki bar, one of the last performances before Christmas. Up at street level, two unwelcome guests had arrived. They were not fans. They were men with bushy beards, one holding a bullhorn, the other a placard that depicted a drag queen holding a screaming baby and the hashtag #stopdragqueenstoryhour. “Repent, you filthy dog! You are going to burn in hell!” the one with the bullhorn shouted. “God sent AIDS to deal with people like you!” Madge, as she is known to her friends and adoring fans, was unfazed. “I teach math to middle schoolers,” Madge deadpanned. “You think I haven’t been called some things?” Something was in the water in Austin. In the 1960s, a gang of classics scholars and philosophy professors had rolled into town like bandits, the University of Texas their saloon: William Arrowsmith, chair of the Classics Department, who scandalized the academic humanities with a Harper’s Magazine essay titled “The Shame of the Graduate Schools,” arguing that “the humanists have betrayed the humanities” and that “an alarmingly high proportion of what is published in classics—and in other fields—is simply rubbish or trivia”; John Silber, promoted to dean of the College of Arts and Sciences just ten years after graduating from Yale, who promptly replaced twenty-two department heads, much to the ire of the university’s board; and a third, an unassuming former radio broadcaster from the United Kingdom with a knack for classical languages and only a master’s degree to his name.

Something was in the water in Austin. In the 1960s, a gang of classics scholars and philosophy professors had rolled into town like bandits, the University of Texas their saloon: William Arrowsmith, chair of the Classics Department, who scandalized the academic humanities with a Harper’s Magazine essay titled “The Shame of the Graduate Schools,” arguing that “the humanists have betrayed the humanities” and that “an alarmingly high proportion of what is published in classics—and in other fields—is simply rubbish or trivia”; John Silber, promoted to dean of the College of Arts and Sciences just ten years after graduating from Yale, who promptly replaced twenty-two department heads, much to the ire of the university’s board; and a third, an unassuming former radio broadcaster from the United Kingdom with a knack for classical languages and only a master’s degree to his name. On CBS “60 Minutes” last night, scientists

On CBS “60 Minutes” last night, scientists  China’s rise has been the defining story of the past three decades. No analysis of international economics or politics can ignore it. But the conversation has shifted over time. Before 2017, it was widely believed that China could become a “

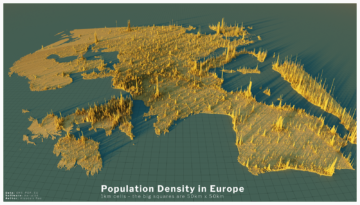

China’s rise has been the defining story of the past three decades. No analysis of international economics or politics can ignore it. But the conversation has shifted over time. Before 2017, it was widely believed that China could become a “ It can be difficult to comprehend the true sizes of megacities, or the global spread of

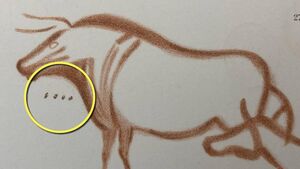

It can be difficult to comprehend the true sizes of megacities, or the global spread of  A London furniture conservator has been credited with a crucial discovery that has helped understand why Ice Age hunter-gatherers drew cave paintings.

A London furniture conservator has been credited with a crucial discovery that has helped understand why Ice Age hunter-gatherers drew cave paintings. You may wonder about the focus on the need for social connections as one grows older, in this book. After all, isn’t friendship usually associated with youth? Education management expert Ravi Acharya would say no to that. After spending his working years in Pune and Ahmedabad, among other places, Acharya moved to Bengaluru. He is lucky to have two of his closest friends live on the same street. Acharya says we don’t realise the importance of actually talking to our friends, in a world dominated by conversations on WhatsApp, Facebook, and other social media. “We friends make it a point to meet once a month,” says Acharya, “and avoid conversations over WhatsApp unless necessary. Such social connections and making an effort toward being in touch is important for active ageing.”

You may wonder about the focus on the need for social connections as one grows older, in this book. After all, isn’t friendship usually associated with youth? Education management expert Ravi Acharya would say no to that. After spending his working years in Pune and Ahmedabad, among other places, Acharya moved to Bengaluru. He is lucky to have two of his closest friends live on the same street. Acharya says we don’t realise the importance of actually talking to our friends, in a world dominated by conversations on WhatsApp, Facebook, and other social media. “We friends make it a point to meet once a month,” says Acharya, “and avoid conversations over WhatsApp unless necessary. Such social connections and making an effort toward being in touch is important for active ageing.” Scientists are harnessing a new way to turn cancer cells into potent, anti-cancer agents. In the latest work from the lab of Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, at

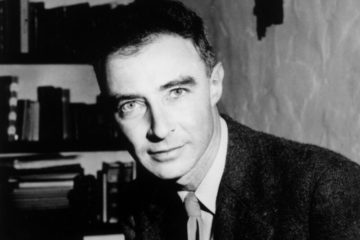

Scientists are harnessing a new way to turn cancer cells into potent, anti-cancer agents. In the latest work from the lab of Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, at  Nearly 70 years after having his security clearance revoked by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) due to suspicion of being a Soviet spy, Manhattan Project physicist

Nearly 70 years after having his security clearance revoked by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) due to suspicion of being a Soviet spy, Manhattan Project physicist  Just another run-of-the-mill, middle-of-the-road Pinker volume. Which is another way of saying it’s bloody marvelous. What a consummate intellectual this man is! Every one of his books is a bracing river of fluent readability to delight the non-specialist. Yet each one simultaneously earns its place as a major professional contribution to its own field. Grasp the fact that the field is different for each book, and you have the measure of this scholar. Steven Pinker’s professional expertise encompasses linguistics, psychology, history, philosophy, evolutionary theory—the list goes on. There’s even a book on how to write good English—for, sure enough, he is a master of that too.

Just another run-of-the-mill, middle-of-the-road Pinker volume. Which is another way of saying it’s bloody marvelous. What a consummate intellectual this man is! Every one of his books is a bracing river of fluent readability to delight the non-specialist. Yet each one simultaneously earns its place as a major professional contribution to its own field. Grasp the fact that the field is different for each book, and you have the measure of this scholar. Steven Pinker’s professional expertise encompasses linguistics, psychology, history, philosophy, evolutionary theory—the list goes on. There’s even a book on how to write good English—for, sure enough, he is a master of that too.