Category: Recommended Reading

The Frozen Politics of Social Security

James G. Chappel in the Boston Review:

Social Security is back in the news. Some Republicans are angling to reduce benefits, while Democrats are posing as the valiant saviors of the popular program. The end result, most likely, is that nothing will happen. We have seen this story before, because this is roughly where the politics of Social Security have been stuck for about forty years. It’s a problem because the system truly does need repair, and the endless conflict between debt-obsessed Republicans and stalwart Democrats will not generate the progressive reforms we need.

Social Security is back in the news. Some Republicans are angling to reduce benefits, while Democrats are posing as the valiant saviors of the popular program. The end result, most likely, is that nothing will happen. We have seen this story before, because this is roughly where the politics of Social Security have been stuck for about forty years. It’s a problem because the system truly does need repair, and the endless conflict between debt-obsessed Republicans and stalwart Democrats will not generate the progressive reforms we need.

Social Security, believe it or not, has a utopian heart: the idea that all Americans deserve a life of dignity and public support once they become old or disabled. This vision does, for now, remain utopian: many Americans are right to worry that, without savings or private pensions, their older years will be just as precarious and austere as their younger ones. Social Security is nonetheless the lynchpin of the U.S. welfare system, such as it is.

More here.

Geoffrey Hinton: The Foundations of Deep Learning

Jena Romanticism And The Art Of Being Selfish

Anthony Curtis Adler at the LARB:

Magnificent Rebels revels in minutiae. But it also has a grander point to make. It wants to ask the big question — “why we are who we are.” The first step in answering this “is to look at us as individuals — when did we begin to be as selfish as we are today?” For Wulf, Jena is at the heart of this story: the Jena Set, we are to learn, was “bound by an obsession with the free self at a time when most of the world was ruled by monarchs and leaders who controlled many aspects of their subjects’ lives.” And so, they “invented” the self.

Magnificent Rebels revels in minutiae. But it also has a grander point to make. It wants to ask the big question — “why we are who we are.” The first step in answering this “is to look at us as individuals — when did we begin to be as selfish as we are today?” For Wulf, Jena is at the heart of this story: the Jena Set, we are to learn, was “bound by an obsession with the free self at a time when most of the world was ruled by monarchs and leaders who controlled many aspects of their subjects’ lives.” And so, they “invented” the self.

It is, however, precisely in addressing this grander question that Magnificent Rebels fails most magnificently. While Fichte’s radical attempt to ground Immanuel Kant’s philosophy in the self-and-other-positing “I” is reduced to a caricature, this very caricature carries Wulf’s entire argument: it justifies her in conceiving the self as an invention, and of understanding the egoism and narcissism of her extravagant characters as practical Fichteanism. Fichte, however, did not invent the self; rather, he invented the idea of the transcendental self as the self-positing, self-inventing, radically inventive ground of the empirical self. Friedrich Schlegel, Schelling, and Novalis, as well as Hölderlin and Hegel, were all, to be sure, deeply influenced by Fichte, but they also almost immediately recognized the one-sidedness of his early system.

more here.

Living, Remembering and Forgetting China’s Cultural Revolution

Jeffrey Wasserstrom at Literary Review:

Red Memory is not just an engagingly written book but also, for two reasons, a much-needed one. It is valuable, first, because it helps clear up lingering popular misunderstandings of a major event in Chinese history. The Cultural Revolution and its legacy have generated a rich scholarly literature, which Branigan mines. But many non-specialists still have a vision of it formed by one or two moving memoirs they have read. The problem is that some of the most influential of these make it easy for readers to assume that China’s population is made up of two groups: former Cultural Revolution perpetrators and their descendants and former Cultural Revolution victims and their descendants. In fact, the twists and turns of the event were such that many people were perpetrators at one point and victims at another. Many families had members who moved between these two categories.

Red Memory is not just an engagingly written book but also, for two reasons, a much-needed one. It is valuable, first, because it helps clear up lingering popular misunderstandings of a major event in Chinese history. The Cultural Revolution and its legacy have generated a rich scholarly literature, which Branigan mines. But many non-specialists still have a vision of it formed by one or two moving memoirs they have read. The problem is that some of the most influential of these make it easy for readers to assume that China’s population is made up of two groups: former Cultural Revolution perpetrators and their descendants and former Cultural Revolution victims and their descendants. In fact, the twists and turns of the event were such that many people were perpetrators at one point and victims at another. Many families had members who moved between these two categories.

more here.

Tuesday Poem

Ode to Herb Kent

Your voice crawls across the dashboard of Grandma’s Dodge Dynasty on the way home from Lilydale First Baptist. You sing a cocktail of static and bass. Sound like you dressed to the nines: cowboy hat, fur coat & alligator boots. Sound like you lotion every tooth. You a walking discography, South Side griot, keeper of crackle & dust in the grooves. You fell in love with a handmade box of wires at 16 and been behind the booth ever since. From wbez to V103, you be the Coolest Gent, King of the Dusties. Your voice wafts down from the ceiling at the Hair Lab. You supply the beat for Kym to tap her comb to. Her brown fingers paint my scalp with white grease to the tunes of Al & Barry & Luther. Your voice: an inside-out yawn, the sizzle of hot iron on fresh perm, the song inside the blackest seashell washed up on a sidewalk in Bronzeville. You soundtrack the church picnic, trunk party, Cynthia’s 50th birthday bash, the car ride to school, choir, Checkers. Your voice stretch across our eardrums like Daddy asleep on the couch. Sound like Grandma’s sweet potato pie, sound like the cigarettes she hide in her purse for rough days. You showed us what our mommas’ mommas must’ve moved to. When the West Side rioted the day MLK died, you were audio salve to the burning city, people. Your voice a soft sermon soothing the masses, speaking coolly to flames, spinning black records across the airwaves, spreading the gospel of soul in a time of fire. Joycetta says she bruised her thumbs snappin’ to Marvin’s “Got to Give It Up” and I believe her.

by Jamila Woods

from:Poetry, December

Our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written. Black Americans have fought to make them true

Nicole Hannah-Jones in The New York Times:

My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine. Our corner lot, which had been redlined by the federal government, was along the river that divided the black side from the white side of our Iowa town. At the edge of our lawn, high on an aluminum pole, soared the flag, which my dad would replace as soon as it showed the slightest tatter.

My dad always flew an American flag in our front yard. The blue paint on our two-story house was perennially chipping; the fence, or the rail by the stairs, or the front door, existed in a perpetual state of disrepair, but that flag always flew pristine. Our corner lot, which had been redlined by the federal government, was along the river that divided the black side from the white side of our Iowa town. At the edge of our lawn, high on an aluminum pole, soared the flag, which my dad would replace as soon as it showed the slightest tatter.

My dad was born into a family of sharecroppers on a white plantation in Greenwood, Miss., where black people bent over cotton from can’t-see-in-the-morning to can’t-see-at-night, just as their enslaved ancestors had done not long before. The Mississippi of my dad’s youth was an apartheid state that subjugated its near-majority black population through breathtaking acts of violence. White residents in Mississippi lynched more black people than those in any other state in the country, and the white people in my dad’s home county lynched more black residents than those in any other county in Mississippi, often for such “crimes” as entering a room occupied by white women, bumping into a white girl or trying to start a sharecroppers union. My dad’s mother, like all the black people in Greenwood, could not vote, use the public library or find work other than toiling in the cotton fields or toiling in white people’s houses. So in the 1940s, she packed up her few belongings and her three small children and joined the flood of black Southerners fleeing North. She got off the Illinois Central Railroad in Waterloo, Iowa, only to have her hopes of the mythical Promised Land shattered when she learned that Jim Crow did not end at the Mason-Dixon line.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

This supercharged tree might help fight climate change

Matt McFarland in CNN:

The problem with trees is that they are too slow.

The problem with trees is that they are too slow.

Part of the issue with catastrophic climate change is that, by some measures, an incredible amount of damage is already done. Even if all the coal-fired power plants were magically turned into wind and solar overnight, and all our cars were electric, all the greenhouse gases that we pumped into our atmosphere for 200 years would still be there. Trees could, theoretically, help fix that. As they grow, they absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and, long story short, turn it into wood. But many trees only grow a foot or less per year. To not just halt climate change, but actually reverse it, someone would have to invent a tree that can grow much, much faster.

Living Carbon, a San Francisco-based company, says it’s done exactly that.

The startup says it’s genetically modified hybrid poplar trees to grow faster so they’ll absorb more carbon dioxide and help minimize the damage of climate change. Carbon dioxide has grown rapidly in the atmosphere since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, leading to extreme climate effects. The startup says it edits the genes of the trees to speed up photosynthesis, the process that plants use to make food from carbon dioxide and water. This enables the trees to grow faster with the extra energy, according to the company. In one case, a tree it modified accumulated 53% more mass during five months of growth, according to a report Living Carbon published earlier this year.

More here.

Sunday, February 19, 2023

The poetic history of David Graeber

Justin E. H. Smith in The New Statesman:

Was there really a colony known as “Libertalia”, founded by Enlightened pirates on the north-east coast of Madagascar in the early 18th century?

Was there really a colony known as “Libertalia”, founded by Enlightened pirates on the north-east coast of Madagascar in the early 18th century?

In 2021’s The Dawn of Everything, co-written with the British archaeologist David Wengrow, as well as in his new posthumously published book Pirate Enlightenment, out 26 January, the late David Graeber has claimed as his signature method a bold hermeneutic charity towards unreliable sources. These include early-modern travel reports, memoirs written from vague and embellished recollections, and even overtly fictional adventure tales.

Graeber is not alone among historical anthropologists in this relative openness. The French anthropological theorist Philippe Descola has warned against dismissing such sources as Hans Staden’s True History: An Account of Cannibal Activity in Brazil (1557) in our effort to reconstruct Amazonian cultural practices in the early contact period. Recourse to such historical materials is simply faute de mieux, for want of something better: we may appeal to the material-cultural traces of non-textual societies, such as are found in much of Amazonia and Madagascar in the early-modern era, and we may speak with living representatives of these societies as vessels and transmitters of oral history. But both of these methods are bound to mislead – not because of dishonesty, but because of the inherent tendency of cultural information to corrupt over time.

More here.

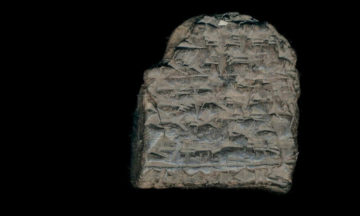

Some 3,700 years ago, an enslaved girl, a barber, and a king crossed paths in a city by the Euphrates

Amanda H Podany in Aeon:

I was sitting in a quiet office in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a clay tablet in my hand, using a magnifying glass to make out words that had been inscribed on it in small, careful, wedge-shaped signs known as cuneiform. It looked diminutive in my palm, just 38.5 mm (1.5 inches) wide and 33 mm (1.3 inches) tall. On it, an ancient scribe had written a list of a dozen names. What lay behind this little document? Who were the men listed? When and how did they live? More than 3,700 years ago, when the scribe used his sharp stylus to press the names into the clay, listing goods distributed to each person, these men knew one another and worked together. Many of them must have had wives and families and professions. What more could I learn about their world?

I was sitting in a quiet office in the Louvre Museum in Paris, a clay tablet in my hand, using a magnifying glass to make out words that had been inscribed on it in small, careful, wedge-shaped signs known as cuneiform. It looked diminutive in my palm, just 38.5 mm (1.5 inches) wide and 33 mm (1.3 inches) tall. On it, an ancient scribe had written a list of a dozen names. What lay behind this little document? Who were the men listed? When and how did they live? More than 3,700 years ago, when the scribe used his sharp stylus to press the names into the clay, listing goods distributed to each person, these men knew one another and worked together. Many of them must have had wives and families and professions. What more could I learn about their world?

At that point, I was just beginning my graduate research in ancient Middle Eastern history, but I knew I was not the first person to read this tablet. Decades before, in 1923, a French scholar named François Thureau-Dangin had travelled to eastern Syria, searching for the site of an ancient city called Terqa, and he had been given this tablet, along with a handful of others, and had brought them back to the Louvre.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Johanna Hoffman on Speculative Futures of Cities

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

Cities are incredibly important to modern life, and their importance is only growing. As Geoffrey West points out, the world is adding urban areas equivalent to the population of San Francisco once every four days. How those areas get designed and structured is a complicated interplay between top-down planning and the collective choices of millions of inhabitants. As the world is changing and urbanization increases, it will be crucial to imagine how cities might serve our needs even better. Johanna Hoffman is an urbanist who harnesses imagination to make cities more sustainable and equitable.

Cities are incredibly important to modern life, and their importance is only growing. As Geoffrey West points out, the world is adding urban areas equivalent to the population of San Francisco once every four days. How those areas get designed and structured is a complicated interplay between top-down planning and the collective choices of millions of inhabitants. As the world is changing and urbanization increases, it will be crucial to imagine how cities might serve our needs even better. Johanna Hoffman is an urbanist who harnesses imagination to make cities more sustainable and equitable.

More here.

Steven Pinker: Will ChatGPT supplant us as writers, thinkers?

Alvin Powell in The Harvard Gazette:

Steven Pinker thinks ChatGPT is truly impressive — and will be even more so once it “stops making stuff up” and becomes less error-prone. Higher education, indeed, much of the world, was set abuzz in November when OpenAI unveiled its ChatGPT chatbot capable of instantly answering questions (in fact, composing writing in various genres) across a range of fields in a conversational and ostensibly authoritative fashion. Utilizing a type of AI called a large language model (LLM), ChatGPT is able to continuously learn and improve its responses. But just how good can it get? Pinker, the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology, has investigated, among other things, links between the mind, language, and thought in books like the award-winning bestseller “The Language Instinct” and has a few thoughts of his own on whether we should be concerned about ChatGPT’s potential to displace humans as writers and thinkers. Interview was edited for clarity and length.

Steven Pinker thinks ChatGPT is truly impressive — and will be even more so once it “stops making stuff up” and becomes less error-prone. Higher education, indeed, much of the world, was set abuzz in November when OpenAI unveiled its ChatGPT chatbot capable of instantly answering questions (in fact, composing writing in various genres) across a range of fields in a conversational and ostensibly authoritative fashion. Utilizing a type of AI called a large language model (LLM), ChatGPT is able to continuously learn and improve its responses. But just how good can it get? Pinker, the Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology, has investigated, among other things, links between the mind, language, and thought in books like the award-winning bestseller “The Language Instinct” and has a few thoughts of his own on whether we should be concerned about ChatGPT’s potential to displace humans as writers and thinkers. Interview was edited for clarity and length.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Thinking About Unamuno’s San Manuel Bueno, Mártir

Joined by Emily Dickinson, Muriel Rukeyser, and Theodore Roethke

San Manuel . . . the priest who kept

his poor parish in the faith

burnished their bright hope of heaven

(hope is a thing with feathers)

it is best not to think these days

about what . . . what the newspapers report so reasonably

. . . (I lived in the first century of world wars,

. . . most days I was more or less insane)

today’s weather . . . an endless rain of feathers

when the passenger pigeon . . . now extinct

had not yet been converted

to fashion . . . slaughtered . . . its plumage plucked

for the elegant hats of American women

. . . (those catlike immaculate

. . . . . . creatures for whom the world works)

when the migrating flocks still passed

overhead . . . a billion strong . . . the farmers said

bird lime turned the woods white

the sky was dark for a week

And San Manuel? Late in the story we learn

he did not believe in the hope

he kept alive . . . believing as he did

(like his author) in the sustaining power

of fiction

by Elenor Wilner

from Poetry

Poetry Magazine, 2006

Friedrich Cerha (1926 – 2023) Composer And Conductor

Raquel Welch (1940 – 2023) Actor

David Jolicoeur (Trugoy) (1968 – 2023) Rapper

A juicy new legal filing reveals who really controls Fox News

Andrew Prokop in Vox:

The way Dominion’s attorneys tell the story, the problem really started when, late on election night, Fox News’s decision desk called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden — and no other networks joined them. The Fox call was consequential, seriously undercutting Trump’s hope of portraying the election outcome as genuinely in question. It also was, probably, premature. The consensus among other decision desks and election wonks was that Fox called the state too quickly, considering how much of the vote remained uncounted and where and whom those uncounted votes were coming from. Other outlets left Arizona uncalled for more than a week as counting continued, and Biden’s lead shrank there. Biden eventually won the state by a mere 0.3 percent margin.

The way Dominion’s attorneys tell the story, the problem really started when, late on election night, Fox News’s decision desk called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden — and no other networks joined them. The Fox call was consequential, seriously undercutting Trump’s hope of portraying the election outcome as genuinely in question. It also was, probably, premature. The consensus among other decision desks and election wonks was that Fox called the state too quickly, considering how much of the vote remained uncounted and where and whom those uncounted votes were coming from. Other outlets left Arizona uncalled for more than a week as counting continued, and Biden’s lead shrank there. Biden eventually won the state by a mere 0.3 percent margin.

But the Fox personalities’ real concern was not so much with the facts or technical details of election wonkery as with the optics. In getting out on a limb and calling Arizona for Biden when no one else was doing so, it appeared to Fox’s pro-Trump viewers like the network was shivving Trump. “We worked really hard to build what we have. Those fuckers [at the decision desk] are destroying our credibility. It enrages me,” Fox News host Tucker Carlson wrote to his producer on November 5. He went on to say that what Trump is good at is “destroying things,” adding, “He could easily destroy us if we play it wrong.”

On November 7, Carlson again wrote to his producer when Fox called Biden as the winner nationally (this time, alongside the other major networks). “Do the executives understand how much credibility and trust we’ve lost with our audience? We’re playing with fire, for real,” he wrote.

The fear of alienating the audience was particularly acute because another conservative cable network with a more conspiratorial bent, Newsmax, was covering Trump’s stolen election claims far more uncritically. “An alternative like newsmax could be devastating to us,” Carlson continued.

Fox News anchor Dana Perino wrote to a Republican strategist about “this RAGING issue about fox losing tons of viewers and many watching — get this — newsmax! Our viewers are so mad about the election calls…” And Fox News CEO Suzanne Scott told another executive that the political team did not understand “the impact to the brand and the arrogance in calling AZ.”

More here.

The 1619 Project and the Long Battle Over U.S. History

Jake Silverstein in The New York Times:

On Jan. 28, 2019, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who has been a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine since 2015, came to one of our weekly ideas meetings with a very big idea. My notes from the meeting simply say, “NIKOLE: special issue on the 400th anniversary of African slaves coming to U.S.,” a milestone that was approaching that August. This wasn’t the first time Nikole had brought up 1619. As an investigative journalist who often focuses on racial inequalities in education, Nikole has frequently turned to history to explain the present. Sometimes, reading a draft of one of her articles, I’d ask if she might include even more history, to which she would remark that if I gave her more space, she would be happy to take it all the way back to 1619. This was a running joke, but it was also a reflection of how Nikole had been cultivating the idea for what became the 1619 Project for many years. Following that January meeting, she led an editorial process that over the next six months developed the idea into a special issue of the magazine, a special section of the newspaper and a multiepisode podcast series. Next week we are publishing a book that expands on the magazine issue and represents the fullest expression of her idea to date.

On Jan. 28, 2019, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who has been a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine since 2015, came to one of our weekly ideas meetings with a very big idea. My notes from the meeting simply say, “NIKOLE: special issue on the 400th anniversary of African slaves coming to U.S.,” a milestone that was approaching that August. This wasn’t the first time Nikole had brought up 1619. As an investigative journalist who often focuses on racial inequalities in education, Nikole has frequently turned to history to explain the present. Sometimes, reading a draft of one of her articles, I’d ask if she might include even more history, to which she would remark that if I gave her more space, she would be happy to take it all the way back to 1619. This was a running joke, but it was also a reflection of how Nikole had been cultivating the idea for what became the 1619 Project for many years. Following that January meeting, she led an editorial process that over the next six months developed the idea into a special issue of the magazine, a special section of the newspaper and a multiepisode podcast series. Next week we are publishing a book that expands on the magazine issue and represents the fullest expression of her idea to date.

This book, which is called “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story,” arrives amid a prolonged debate over the version of the project we published two years ago. That project made a bold claim, which remains the central idea of the book: that the moment in August 1619 when the first enslaved Africans arrived in the English colonies that would become the United States could, in a sense, be considered the country’s origin.

More here. (Note: Throughout February, at least one post will be dedicated to Black History Month. The theme for 2023 is Black Resistance. Please send us anything you think is relevant for inclusion)

Saturday, February 18, 2023

Securitizing the Transition

Advait Arun in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis:

Advait Arun in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis:

In the eyes of the IMF, a G20 panel, and, lately, the US Treasury Secretary, the time has come for multilateral development banks to adapt their development mandates to the logic of derisking. This tactic—lauded as a solution for “mobilizing” the trillions necessary to achieve the green transition—demands that public entities shift private investors’ risks onto their own balance sheets, incentivizing investment to meet the world’s infrastructure needs.

Although development banks have floated serious plans to reorient themselves toward catalyzing private investment since the “billions to trillions” hype in 2016, such efforts never took off. The World Bank’s recently leaked “Evolution Roadmap” is its latest attempt to kickstart derisking at a global scale.

But the roadmap’s emphasis on mobilizing private finance through derisking obscures one proposal that on the surface appears to run the other direction. Securitization allows public entities and development banks to offload their assets to the private sector, thereby transferring risk away from themselves and freeing up their balance sheets for more immediate lending. To be sure, securitization still fits snugly within economist Daniela Gabor’s Wall Street Consensus, in which governments meet development goals by turning public services into investment opportunities for private finance. But while derisking calls for the public sector to shoulder additional risks, securitization calls for shrugging them off.

How would securitizing the World Bank’s portfolio work, and how does this tactic relate to the larger derisking turn in development finance? Is securitization a preferred alternative to derisking, or does it align with its broader logic?

More here.

The Blindness of Colorblindness

Ira Katznelson in Boston Review:

Ira Katznelson in Boston Review:

First published in 2005, my book When Affirmative Action Was White answered a question Lyndon Johnson posed at Howard University’s graduation ceremony in June 1965: Why had the large gap between Black and white income and wealth at the end of World War II widened during two decades marked by dramatic economic growth and widespread prosperity?

The book told the story of sanctioned racism during and just after the Great Depression and World War II. During this period, master politicians from the South proudly protected their region’s entrenched white supremacy by passing landmark laws that made the great majority of Americans, the overwhelming white majority, more prosperous and more secure, while leaving out most African Americans, in full or in part. Ever since, many persons left behind have continued to experience deep poverty, together with social and spatial isolation.

The book’s account of blatant discrimination has been challenged in the seventeen years since it appeared. Two lines of argument are especially noteworthy. One questions whether domestics and farm laborers—critical categories of Black employment—were in fact kept out of Social Security for reasons of race. The second argues that the book underestimates the bounty of the GI Bill for Black Americans. Both objections deserve respectful review.

More here.