Andrew Prokop in Vox:

The way Dominion’s attorneys tell the story, the problem really started when, late on election night, Fox News’s decision desk called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden — and no other networks joined them. The Fox call was consequential, seriously undercutting Trump’s hope of portraying the election outcome as genuinely in question. It also was, probably, premature. The consensus among other decision desks and election wonks was that Fox called the state too quickly, considering how much of the vote remained uncounted and where and whom those uncounted votes were coming from. Other outlets left Arizona uncalled for more than a week as counting continued, and Biden’s lead shrank there. Biden eventually won the state by a mere 0.3 percent margin.

The way Dominion’s attorneys tell the story, the problem really started when, late on election night, Fox News’s decision desk called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden — and no other networks joined them. The Fox call was consequential, seriously undercutting Trump’s hope of portraying the election outcome as genuinely in question. It also was, probably, premature. The consensus among other decision desks and election wonks was that Fox called the state too quickly, considering how much of the vote remained uncounted and where and whom those uncounted votes were coming from. Other outlets left Arizona uncalled for more than a week as counting continued, and Biden’s lead shrank there. Biden eventually won the state by a mere 0.3 percent margin.

But the Fox personalities’ real concern was not so much with the facts or technical details of election wonkery as with the optics. In getting out on a limb and calling Arizona for Biden when no one else was doing so, it appeared to Fox’s pro-Trump viewers like the network was shivving Trump. “We worked really hard to build what we have. Those fuckers [at the decision desk] are destroying our credibility. It enrages me,” Fox News host Tucker Carlson wrote to his producer on November 5. He went on to say that what Trump is good at is “destroying things,” adding, “He could easily destroy us if we play it wrong.”

On November 7, Carlson again wrote to his producer when Fox called Biden as the winner nationally (this time, alongside the other major networks). “Do the executives understand how much credibility and trust we’ve lost with our audience? We’re playing with fire, for real,” he wrote.

The fear of alienating the audience was particularly acute because another conservative cable network with a more conspiratorial bent, Newsmax, was covering Trump’s stolen election claims far more uncritically. “An alternative like newsmax could be devastating to us,” Carlson continued.

Fox News anchor Dana Perino wrote to a Republican strategist about “this RAGING issue about fox losing tons of viewers and many watching — get this — newsmax! Our viewers are so mad about the election calls…” And Fox News CEO Suzanne Scott told another executive that the political team did not understand “the impact to the brand and the arrogance in calling AZ.”

More here.

On Jan. 28, 2019, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who has been a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine since 2015, came to one of our weekly ideas meetings with a very big idea. My notes from the meeting simply say, “NIKOLE: special issue on the 400th anniversary of African slaves coming to U.S.,” a milestone that was approaching that August. This wasn’t the first time Nikole had brought up 1619. As an investigative journalist who often focuses on racial inequalities in education, Nikole has frequently turned to history to explain the present. Sometimes, reading a draft of one of her articles, I’d ask if she might include even more history, to which she would remark that if I gave her more space, she would be happy to take it all the way back to 1619. This was a running joke, but it was also a reflection of how Nikole had been cultivating the idea for what became

On Jan. 28, 2019, Nikole Hannah-Jones, who has been a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine since 2015, came to one of our weekly ideas meetings with a very big idea. My notes from the meeting simply say, “NIKOLE: special issue on the 400th anniversary of African slaves coming to U.S.,” a milestone that was approaching that August. This wasn’t the first time Nikole had brought up 1619. As an investigative journalist who often focuses on racial inequalities in education, Nikole has frequently turned to history to explain the present. Sometimes, reading a draft of one of her articles, I’d ask if she might include even more history, to which she would remark that if I gave her more space, she would be happy to take it all the way back to 1619. This was a running joke, but it was also a reflection of how Nikole had been cultivating the idea for what became  Advait Arun in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis:

Advait Arun in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis: Ira Katznelson in Boston Review:

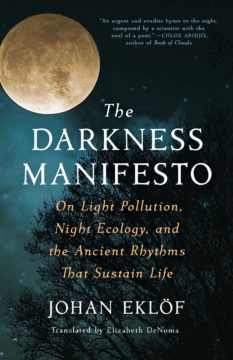

Ira Katznelson in Boston Review: The zoologist Johan Eklöf began to consider the disappearance of darkness in our brightly lit world in 2015, when he was out counting bats in southern Sweden. The surrounding grounds were dark, as they had been decades earlier when his academic adviser had tallied the bat populations in the region’s churches. In the intervening years, however, those churches — whose belfries are famously appreciated by the winged mammals — had been illuminated with floodlights. “I started to think, how do the bats actually react to this?” Eklöf says.

The zoologist Johan Eklöf began to consider the disappearance of darkness in our brightly lit world in 2015, when he was out counting bats in southern Sweden. The surrounding grounds were dark, as they had been decades earlier when his academic adviser had tallied the bat populations in the region’s churches. In the intervening years, however, those churches — whose belfries are famously appreciated by the winged mammals — had been illuminated with floodlights. “I started to think, how do the bats actually react to this?” Eklöf says. To vindicate indicates one of two aims: to make a defense or to stake a claim. With the Vindication of the Rights of Men, published in 1790, Wollstonecraft upheld the natural rights of man, a notion enthroned by the revolutionaries in their “Declaration of the Rights of Man,” embraced by Thomas Paine in his fiery pamphlet Rights of Man, and excoriated by Burke in his Reflections. Two years later, though, and to the shock of her critics, Wollstonecraft pivoted from defense to offense—in both senses of the word—by making a jaw-dropping claim. Natural rights, she declared, also belong to the other half of humankind: women. “I love man as my fellow,” she proclaimed in the Vindication of the Rights of Woman, “but his sceptre, real or usurped, extends not to me, unless the reason of an individual demands my homage.” Wollstonecraft was not alone in making so extraordinary a claim. The following year in France, the playwright Olympe de Gouges published her Declaration of the Rights of Woman. Demanding full civil and political rights for both sexes, de Gouges insisted that a woman’s place in the public square was side by side, as a full equal, to man.

To vindicate indicates one of two aims: to make a defense or to stake a claim. With the Vindication of the Rights of Men, published in 1790, Wollstonecraft upheld the natural rights of man, a notion enthroned by the revolutionaries in their “Declaration of the Rights of Man,” embraced by Thomas Paine in his fiery pamphlet Rights of Man, and excoriated by Burke in his Reflections. Two years later, though, and to the shock of her critics, Wollstonecraft pivoted from defense to offense—in both senses of the word—by making a jaw-dropping claim. Natural rights, she declared, also belong to the other half of humankind: women. “I love man as my fellow,” she proclaimed in the Vindication of the Rights of Woman, “but his sceptre, real or usurped, extends not to me, unless the reason of an individual demands my homage.” Wollstonecraft was not alone in making so extraordinary a claim. The following year in France, the playwright Olympe de Gouges published her Declaration of the Rights of Woman. Demanding full civil and political rights for both sexes, de Gouges insisted that a woman’s place in the public square was side by side, as a full equal, to man. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr.  The experiment that became known as the Elephant Man trial began one spring morning, in 2006, when clinicians at London’s Northwick Park Hospital infused six healthy young men with an experimental drug. Developers hoped to market TGN-1412, a genetically engineered monoclonal antibody, as a treatment for lymphocytic leukemia and rheumatoid arthritis, but they found that in just over an hour, the men grew restless. “They began tearing their shirts off complaining of fever,” one trial participant, who received a placebo, told a London tabloid. “Some screamed out that their heads were going to explode. After that they started fainting, vomiting and writhing around in their beds.” The heads of some of the subjects swelled to elephantine proportions. Within sixteen hours, all six were in the intensive-care unit suffering from multiple organ failure. They had narrowly survived a potentially fatal inflammatory response known as a cytokine storm.

The experiment that became known as the Elephant Man trial began one spring morning, in 2006, when clinicians at London’s Northwick Park Hospital infused six healthy young men with an experimental drug. Developers hoped to market TGN-1412, a genetically engineered monoclonal antibody, as a treatment for lymphocytic leukemia and rheumatoid arthritis, but they found that in just over an hour, the men grew restless. “They began tearing their shirts off complaining of fever,” one trial participant, who received a placebo, told a London tabloid. “Some screamed out that their heads were going to explode. After that they started fainting, vomiting and writhing around in their beds.” The heads of some of the subjects swelled to elephantine proportions. Within sixteen hours, all six were in the intensive-care unit suffering from multiple organ failure. They had narrowly survived a potentially fatal inflammatory response known as a cytokine storm. We had been messaging each other on Boxing Day, trying to fix a date for a drink. Then all went silent. I assumed that Hanif Kureishi was too busy enjoying himself in Rome. Only later did I discover that

We had been messaging each other on Boxing Day, trying to fix a date for a drink. Then all went silent. I assumed that Hanif Kureishi was too busy enjoying himself in Rome. Only later did I discover that

Women’s rights in Iran saw

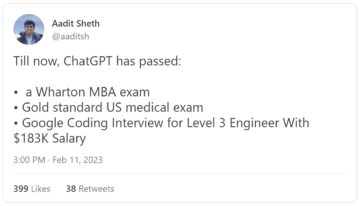

Women’s rights in Iran saw  We’re supposedly on the brink of an artificial intelligence breakthrough. The bots are already communicating—at least they’re stringing together words and creating images. Some of those images are even kind of cool, especially if you’re into that sophomore dorm room surrealist aesthetic. GPT-3, and, more recently, chatGPT, two tools from OpenAI (which recently

We’re supposedly on the brink of an artificial intelligence breakthrough. The bots are already communicating—at least they’re stringing together words and creating images. Some of those images are even kind of cool, especially if you’re into that sophomore dorm room surrealist aesthetic. GPT-3, and, more recently, chatGPT, two tools from OpenAI (which recently  Lurking behind the concerns of Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida, over the content of a proposed high school course in African American Studies, is a long and complex series of debates about the role of slavery and race in American classrooms. “We believe in teaching kids facts and how to think, but we don’t believe they should have an agenda imposed on them,” Governor DeSantis said. He also decried what he called “indoctrination.”

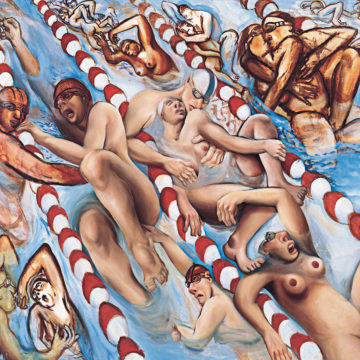

Lurking behind the concerns of Ron DeSantis, the governor of Florida, over the content of a proposed high school course in African American Studies, is a long and complex series of debates about the role of slavery and race in American classrooms. “We believe in teaching kids facts and how to think, but we don’t believe they should have an agenda imposed on them,” Governor DeSantis said. He also decried what he called “indoctrination.” THERE ARE HISTORICAL MOMENTS that transform the industry standard, and sometimes they have deep, traceable roots. An opportunity to understand this process is provided by an exhibition of artist Nicole Eisenman’s work opening in March at Munich’s Museum Brandhorst. Curated by Monika Bayer-Wermuth and Mark Godfrey, the show, especially its revisitation of startlingly explicit lesbian works from the 1990s, will allow viewers to enjoy Eisenman’s beautiful, widely appreciated, and highly valued artworks. The fifty-seven-year-old, French-born, New York–raised painter, sculptor, and creator of wild, passionate murals and drawings has taken a bad-boy, oppositional, and sometimes dramatically risky path to becoming one of the world’s most successful living artists. Somehow, the seas parted and—at times in spite of herself—Eisenman has thrived, has been approved of, and is now in some ways iconic. Beyond the quality of her work, how did it happen that exclusionary criteria that kept a range of lesbian imagery out of the mainstream were lifted?

THERE ARE HISTORICAL MOMENTS that transform the industry standard, and sometimes they have deep, traceable roots. An opportunity to understand this process is provided by an exhibition of artist Nicole Eisenman’s work opening in March at Munich’s Museum Brandhorst. Curated by Monika Bayer-Wermuth and Mark Godfrey, the show, especially its revisitation of startlingly explicit lesbian works from the 1990s, will allow viewers to enjoy Eisenman’s beautiful, widely appreciated, and highly valued artworks. The fifty-seven-year-old, French-born, New York–raised painter, sculptor, and creator of wild, passionate murals and drawings has taken a bad-boy, oppositional, and sometimes dramatically risky path to becoming one of the world’s most successful living artists. Somehow, the seas parted and—at times in spite of herself—Eisenman has thrived, has been approved of, and is now in some ways iconic. Beyond the quality of her work, how did it happen that exclusionary criteria that kept a range of lesbian imagery out of the mainstream were lifted? ‘M

‘M