Stephen Mulhall in the London Review of Books:

Stephen Mulhall in the London Review of Books:

For David Edmonds, and for many other philosophers, Derek Parfit, who died in 2017, was one of the greatest moral thinkers of the past century, perhaps even since John Stuart Mill. Edmonds rightly believes that if Parfit’s ideas about personal identity, rationality and equality were absorbed into our moral and political thinking, they would radically alter our beliefs about punishment, the distribution of social resources, our relationship to future generations, and more. So it’s easy to see why he wants to make Parfit’s ideas more widely known outside the academy. What is less easy to understand is his belief that the best, or even an appropriate, way of achieving this goal is to write a biography of him.

There was a time when biographies of philosophers weren’t just common, but expected and even required. Following Socrates, the great schools of Hellenistic philosophy (the Stoics, the Epicureans, the Neoplatonists) all tried to encourage the pursuit of a certain kind of life. For them, philosophy wasn’t primarily something you learned, but something you practised, with a view to self-transformation. So it was indispensable in critically evaluating a philosopher to critically evaluate their way of life, for that life was the definitive expression of their philosophy, and their writings were primarily a means of achieving that essential work on the self.

More here.

A Boston Review Forum, with a lead piece by Christine Sypnowich:

A Boston Review Forum, with a lead piece by Christine Sypnowich: Twice, quarterback Patrick Mahomes has led the Kansas City Chiefs to victory in the Super Bowl, the pinnacle of U.S. football. Although most fans have their eyes on the ball as Mahomes prepares to throw, his tongue does something just as interesting. Just as basketball star Michael Jordan did as he went up for a dunk, and dart players often do as they take aim for a bull’s-eye, Mahomes prepares to pass by sticking out his tongue. That may be more than a silly quirk, some scientists say. Those tongue protrusions may improve the accuracy of his hand movements.

Twice, quarterback Patrick Mahomes has led the Kansas City Chiefs to victory in the Super Bowl, the pinnacle of U.S. football. Although most fans have their eyes on the ball as Mahomes prepares to throw, his tongue does something just as interesting. Just as basketball star Michael Jordan did as he went up for a dunk, and dart players often do as they take aim for a bull’s-eye, Mahomes prepares to pass by sticking out his tongue. That may be more than a silly quirk, some scientists say. Those tongue protrusions may improve the accuracy of his hand movements. Ah, the magical season of prizes is once again upon us. Each spring brings, along with warm rains and budding flowers, Fulbrights, Rhodeses, Pulitzers and Guggenheims, as well as Oscars, Tonys and Indies — which are thought of so fondly they come with their own nicknames. Everybody, it seems, loves honors and prizes. And they certainly make for great entertainment. The award ceremonies for literary prizes are usually demure, decorous little things, but award shows on TV are like a country music hoedown. And the Oscars rank so high in the culture that actors measure their worth by rehearsing their acceptance speeches.

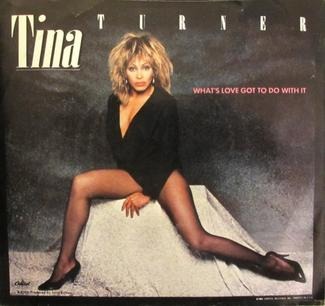

Ah, the magical season of prizes is once again upon us. Each spring brings, along with warm rains and budding flowers, Fulbrights, Rhodeses, Pulitzers and Guggenheims, as well as Oscars, Tonys and Indies — which are thought of so fondly they come with their own nicknames. Everybody, it seems, loves honors and prizes. And they certainly make for great entertainment. The award ceremonies for literary prizes are usually demure, decorous little things, but award shows on TV are like a country music hoedown. And the Oscars rank so high in the culture that actors measure their worth by rehearsing their acceptance speeches. W

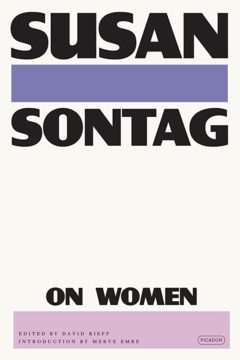

W The great French writer Colette once speculated that “certain highly complex human beings” are marked by their “mental hermaphroditism.” The fabled essayist Susan Sontag was among them. She was a woman, but she dressed in the glamorously genderless garb of an intellectual celebrity and wrote on the weighty topics usually reserved for her male peers. In her journals, she mused that “to be an intellectual is to be attached to the inherent value of plurality.”

The great French writer Colette once speculated that “certain highly complex human beings” are marked by their “mental hermaphroditism.” The fabled essayist Susan Sontag was among them. She was a woman, but she dressed in the glamorously genderless garb of an intellectual celebrity and wrote on the weighty topics usually reserved for her male peers. In her journals, she mused that “to be an intellectual is to be attached to the inherent value of plurality.” When

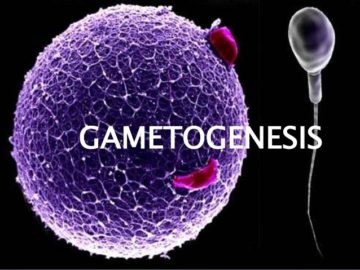

When  Researchers are inching closer to mass-producing eggs and sperm in the lab from ordinary human cells. The technique could provide new ways to treat infertility but also open a Pandora’s box.

Researchers are inching closer to mass-producing eggs and sperm in the lab from ordinary human cells. The technique could provide new ways to treat infertility but also open a Pandora’s box. After 35 years of living in relative control of my decisions, I had decided to see what would happen if I asked AI to control my life instead. Years of suboptimal performance, both personally and professionally, and numerous failed attempts at self-improvement had convinced me there had to be a better way, and I wondered if the collective knowledge hidden inside OpenAI’s hit tech product could help me. But when I asked Sam Altman’s ChatGPT to become my all-powerful leader, it seemed reticent, at least at first.

After 35 years of living in relative control of my decisions, I had decided to see what would happen if I asked AI to control my life instead. Years of suboptimal performance, both personally and professionally, and numerous failed attempts at self-improvement had convinced me there had to be a better way, and I wondered if the collective knowledge hidden inside OpenAI’s hit tech product could help me. But when I asked Sam Altman’s ChatGPT to become my all-powerful leader, it seemed reticent, at least at first. A new generation of drugs is revolutionizing the treatment of obesity and

A new generation of drugs is revolutionizing the treatment of obesity and  Coming up with economic policy is a difficult, unforgiving task. To make the best of it, it helps to work with an accurate model of how the economy works. If you use a misleading model and act on it, you can’t reasonably expect good outcomes: in that scenario, we end up, as JM Keynes warned in the 1930s, with “madmen in authority”, acting according to the precepts of “some defunct economist”.

Coming up with economic policy is a difficult, unforgiving task. To make the best of it, it helps to work with an accurate model of how the economy works. If you use a misleading model and act on it, you can’t reasonably expect good outcomes: in that scenario, we end up, as JM Keynes warned in the 1930s, with “madmen in authority”, acting according to the precepts of “some defunct economist”. W

W I like when the refs touch each other in any way, but especially when all three of them put their arms around one another, huddling to discuss a difficult call. I like watching endless replays of fouls, trying to decide whether something was a block or a charge, or who touched the ball last. I like when the commentators disagree with the refs and when the broadcast cuts to the former ref Steve Javie in some NBA warehouse in New Jersey, standing in front of TV screens, calmly hypothesizing what the refs are discussing.

I like when the refs touch each other in any way, but especially when all three of them put their arms around one another, huddling to discuss a difficult call. I like watching endless replays of fouls, trying to decide whether something was a block or a charge, or who touched the ball last. I like when the commentators disagree with the refs and when the broadcast cuts to the former ref Steve Javie in some NBA warehouse in New Jersey, standing in front of TV screens, calmly hypothesizing what the refs are discussing. 1.

1.  In the twenties, Archie League was spinning, diving, and doing loop-the-loops above the clouds, engine roaring, little plane shaking as he and the other barnstormers in his flying circus entertained folks across Missouri and Illinois. Necks grew stiff from watching, eyes squinted against the light, jaws dropped and air rushing in with every oooohhhh and whoa and oh my sweet Lord Jesus.

In the twenties, Archie League was spinning, diving, and doing loop-the-loops above the clouds, engine roaring, little plane shaking as he and the other barnstormers in his flying circus entertained folks across Missouri and Illinois. Necks grew stiff from watching, eyes squinted against the light, jaws dropped and air rushing in with every oooohhhh and whoa and oh my sweet Lord Jesus.