Category: Recommended Reading

Ian Hacking (1936 – 2023) Philosopher

Ilya Kabakov (1933 – 2023) Artist

Saturday, June 3, 2023

Female Foundering

Sarah Arkebauer in The Baffler:

Sarah Arkebauer in The Baffler:

“THIS ISN’T JUST MY JOB. This is who I am. Anyone who doubts my company doubts me,” says Amanda Seyfried as Elizabeth Holmes in the last year’s Hulu show The Dropout. It’s a claim the real-life Holmes managed to make work for her, until it didn’t, tying the success of Theranos, the company she founded in 2003, to her own personal brand as a serious-minded female science genius. Her rhetoric implied that any criticism of the “Edison,” the blood-testing device that promised to diagnose numerous diseases using only a single drop of blood, ought to be brushed off as sexist bias rather than legitimate critique. In making herself the face of this tech, she cultivated an image of authority, power, innovation, and promises kept though the adoption of the black turtleneck made famous by Apple icon Steve Jobs, her low voice, no-nonsense bun, and (when called for) red lipstick.

The Dropout’s title figures the drop of blood through which Theranos supposedly could accomplish never-yet-seen feats of science in the context of what kicked off the whole endeavor: Holmes’s dropping out of Stanford. Her status as a dropout both fueled her success—she was a genius with no time for formal education, à la Mark Zuckerberg—and also invited doubt. And while dropping out of school is neither a harbinger of failure writ large, nor should it be pathologized in a society that ties college education so tightly to a lifetime of debt, in this case, the choice indicated Holmes’s willingness to step beyond her ken. That is to say, to make claims for which she had no scientific chops or backing. In naming its show, then, Hulu relied on its audience coming to Holmes’s story from the skepticism brought on by her downfall.

More here.

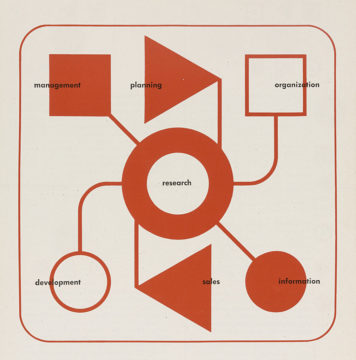

Hollow States

Cedric Durand in Sidecar:

Cedric Durand in Sidecar:

The return of industrial policy is unmissable, catalyzed by the cumulative shocks of Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine as well as longer-term structural issues: the ecological crisis, faltering productivity and alarm at the dependence of Western states on China’s productive apparatus. Together, these factors have steadily undermined governments’ confidence in the ability of private enterprise to drive economic development.

Of course, the ‘entrepreneurial state’ never disappeared, especially in the US. The deep pockets of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the National Institutes of Health have been crucial in maintaining the country’s technological advantage – funding research and product development over the past few decades. Still, it is clear that a substantial shift is taking place. As a group of OECD economists noted, ‘So-called horizontal policies, i.e. interventions available to all firms and which include business framework conditions such as taxes, product or labour market regulations, are increasingly questioned’. Meanwhile, ‘the case for governments to more actively direct the structure of the business sector is gaining traction’. Hundreds of billions of targeted funding is now flooding businesses in the military, high-tech and green sectors on both sides of the Atlantic.

This pivot is part of a broader macro-institutional reconfiguration of capitalism, in which a high-pressure post-pandemic economy has tightened labour markets while the centrality of finance continues to wane. These phenomena are highly complementary: public funding stimulates the economy and may boost job creation, while the administrative allocation of credit serves as an admission that financial markets are unable to attract the investment necessary to meet major conjunctural challenges. At a very general level, this neo-industrial turn should be welcomed, since it implies that political deliberation may play a somewhat greater role in investment decisions. More concretely, though, there is much to worry about.

More here.

Industrial Transformations

Isabel Estevez in Phenomenal World:

Isabel Estevez in Phenomenal World:

The latest US experiment with industrial policy—comprised primarily by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act—has sparked outright opposition and pleas for restraint, but also calls for far more ambitious action.

The divergent responses are representative of the lack of consensus about the nature of the challenges that US industrial policy could or should address. In the broadest sense, industrial policy refers to the deployment of policy tools in order to influence how we create value—what goods (and services) we produce and how we produce them. In economist Ha-Joon Chang’s words, it is a set of “policies aimed at particular industries (and firms as their components) to achieve outcomes that are perceived by the state to be efficient for the economy as a whole.” Mario Cimoli, Giovanni Dosi, and Joseph Stiglitz argue that industrial policies “come together with processes of ‘institutional engineering’ shaping the very nature of the economic actors, the market mechanisms and rules under which they operate, and the boundaries between what is governed by market interactions, and what is not.” These different understandings of industrial policy all recognize the government as a key actor in shaping the world of production in line with a public purpose.

More here.

The Art of Compression: Conjuring a fiction out of almost nothing

Richard Gibson in The Hedgehog Review:

What exactly separates the short story from the novel? As the contemporary Scottish writer William Boyd has observed, the issue is more complicated than it might at first appear. Novelists and short story writers, Boyd points out, rely on the same “literary tools,” including character, plot, setting, title, and dialogue, and their outputs—sentences and paragraphs—look the same on the page. The tempting answer is to fall back on the obvious difference: short stories are just shorter than novels.

What exactly separates the short story from the novel? As the contemporary Scottish writer William Boyd has observed, the issue is more complicated than it might at first appear. Novelists and short story writers, Boyd points out, rely on the same “literary tools,” including character, plot, setting, title, and dialogue, and their outputs—sentences and paragraphs—look the same on the page. The tempting answer is to fall back on the obvious difference: short stories are just shorter than novels.

Already in the late nineteenth century, critics argued that that answer wasn’t good enough. In one of the earliest attempts to define the genre, “The Philosophy of the Short-Story” (1885), Brander Matthews made the case that the short story’s distinctive trait is not length per se. (“The story which is short can be written by anybody who can write at all.”) In Matthews’s view, the short story is defined by its originality, ingenuity, and, above all, “vigorous compression.”

More here.

The healthspan revolution: how to live a long, strong and happy life

John Harris in The Guardian:

Twenty years ago, Peter Attia was working as a trainee surgeon at Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, where he saved countless people facing what he calls “fast death”. “I trained in a very, very violent city,” he tells me. “We were probably averaging 15 or 16 people a day getting shot or stabbed. And, you know, that’s when surgeons can save your life. We’re really good at that.”

Twenty years ago, Peter Attia was working as a trainee surgeon at Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, where he saved countless people facing what he calls “fast death”. “I trained in a very, very violent city,” he tells me. “We were probably averaging 15 or 16 people a day getting shot or stabbed. And, you know, that’s when surgeons can save your life. We’re really good at that.”

What got to him, he says, were the people he treated who were in the midst of dying much more slowly. “All the people with cardiovascular disease, all the people with cancer: we were far less effective at saving those people. We could delay death a little bit, but we weren’t bending the arc of their lives.” Attia and his colleagues often worked 24-hour shifts, leaving him starved of sleep. When he managed to get some rest, he had an endlessly recurring dream, in which he found himself in the middle of the city, holding a padded basket and staring up at a nearby building. Eggs rained down on him, and though he tried to catch as many as he could, most of them inevitably smashed on the pavement.

More here.

Saturday Poem

The Clothes Shrine

It was a whole new sweetness

In the early days to find

Light white muslin blouses

On a see-through nylon line

Drip-drying in the bathroom

Or a nylon slip in the shine

Of its own electricity-

As if St. Brigid once more

Had rigged up a ray of sun

Like the one she’d strung on air

To dry her own cloak on

(Hard-pressed Brigid, so

Unstoppably on the go)-

The damp and slump and unfair

Drag of the workday

Made light of and got through

As usual, brilliantly.

by Seamus Heaney

from Electric Light

farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001

Orwell: A Very English Socialist

Blake Morrison at The Guardian:

The key to his reading of Orwell is what happened to him in Spain. Though married to Eileen only six months before, he was determined to fight for the Republican cause (“Good chaps, the Spaniards, can’t let them down”) and on his return became far more politically engaged: “at last [I] really believe in Socialism, which I never did before”. But he’d seen bullying and infighting too. For the rest of his life and in his two great novels, this was the war he fought, on behalf of a wholesome, English, sweetly C of E brand of socialism, as opposed to Stalinist totalitarianism.

The key to his reading of Orwell is what happened to him in Spain. Though married to Eileen only six months before, he was determined to fight for the Republican cause (“Good chaps, the Spaniards, can’t let them down”) and on his return became far more politically engaged: “at last [I] really believe in Socialism, which I never did before”. But he’d seen bullying and infighting too. For the rest of his life and in his two great novels, this was the war he fought, on behalf of a wholesome, English, sweetly C of E brand of socialism, as opposed to Stalinist totalitarianism.

Equally crucial was that sniper’s bullet, which along with damp Catalan trench warfare damaged his already frail health. Born with defective bronchial tubes, he’d had bouts of pneumonia; after Spain he looked gaunt, haggard, primed for death. He hung on for 12 more years, but ill health is Taylor’s refrain throughout. If he resists making Orwell a caricatural bohemian consumptive, doomed to die young, he can’t disguise the stress and exhaustion Orwell endured in completing Nineteen Eighty-Four.

more here.

Deborah Levy Embodies Strangeness

Simran Hans at the NY Times:

“August Blue” is Levy’s eighth novel, and since her 20s, she has been refining her ability to evoke feeling through writing rather than to narrate it. Her work is deeply influenced by art forms that express the embodied experience, like cinema and dance. “The body in the world,” she said. “How difficult. It is my subject.”

“August Blue” is Levy’s eighth novel, and since her 20s, she has been refining her ability to evoke feeling through writing rather than to narrate it. Her work is deeply influenced by art forms that express the embodied experience, like cinema and dance. “The body in the world,” she said. “How difficult. It is my subject.”

Born in South Africa before moving to England as a child, Levy, 63, is a poet, playwright and author. Writing in The New York Times, the critic Parul Sehgal described Levy’s lucid prose as “light-handed” and leaving “a pleasant sting,” and Levy has been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize twice. In 2020 she was awarded France’s prestigious Prix Femina Étranger for her memoirs “Things I Don’t Want to Know” and “The Cost of Living. ”

more here.

An Evening with Deborah Levy

Friday, June 2, 2023

India’s religious AI chatbots are speaking in the voice of god — and condoning violence

Nadia Nooreyezdan at Rest of World:

In January 2023, when ChatGPT was setting new growth records, Bengaluru-based software engineer Sukuru Sai Vineet launched GitaGPT. The chatbot, powered by GPT-3 technology, provides answers based on the Bhagavad Gita, a 700-verse Hindu scripture. GitaGPT mimics the Hindu god Krishna’s tone — the search box reads, “What troubles you, my child?”

In January 2023, when ChatGPT was setting new growth records, Bengaluru-based software engineer Sukuru Sai Vineet launched GitaGPT. The chatbot, powered by GPT-3 technology, provides answers based on the Bhagavad Gita, a 700-verse Hindu scripture. GitaGPT mimics the Hindu god Krishna’s tone — the search box reads, “What troubles you, my child?”

In the Bhagavad Gita, according to Vineet, Krishna plays a therapist of sorts for the character Arjuna. A religious AI bot works in a similar manner, Vineet told Rest of World, “except you’re not actually talking to Krishna. You’re talking to a bot that’s pretending to be him.”

At least five GitaGPTs have sprung up between January and March this year, with more on the way. Experts have warned that chatbots being allowed to play god might have unintended, and dangerous, consequences. Rest of World found that some of the answers generated by the Gita bots lack filters for casteism, misogyny, and even law. Three of these bots, for instance, say it is acceptable to kill another if it is one’s dharma or duty.

More here.

Why do animals keep evolving into crabs?

Laurel Hamers at Live Science:

A flat, rounded shell. A tail that’s folded under the body. This is what a crab looks like, and apparently what peak performance might look like — at least according to evolution. A crab-like body plan has evolved at least five separate times among decapod crustaceans, a group that includes crabs, lobsters and shrimp. In fact, it’s happened so often that there’s a name for it: carcinization.

A flat, rounded shell. A tail that’s folded under the body. This is what a crab looks like, and apparently what peak performance might look like — at least according to evolution. A crab-like body plan has evolved at least five separate times among decapod crustaceans, a group that includes crabs, lobsters and shrimp. In fact, it’s happened so often that there’s a name for it: carcinization.

So why do animals keep evolving into crab-like forms? Scientists don’t know for sure, but they have lots of ideas.

Carcinization is an example of a phenomenon called convergent evolution, which is when different groups independently evolve the same traits. It’s the same reason both bats and birds have wings. But intriguingly, the crab-like body plan has emerged many times among very closely related animals.

More here.

Exploring Gender Bias in Six Key Domains of Academic Science: An Adversarial Collaboration

Stephen J. Ceci, Shulamit Kahn, and Wendy M. Williams at the APS:

We synthesized the vast, contradictory scholarly literature on gender bias in academic science from 2000 to 2020. In the most prestigious journals and media outlets, which influence many people’s opinions about sexism, bias is frequently portrayed as an omnipresent factor limiting women’s progress in the tenure-track academy. Claims and counterclaims regarding the presence or absence of sexism span a range of evaluation contexts. Our approach relied on a combination of meta-analysis and analytic dissection. We evaluated the empirical evidence for gender bias in six key contexts in the tenure-track academy: (a) tenure-track hiring, (b) grant funding, (c) teaching ratings, (d) journal acceptances, (e) salaries, and (f) recommendation letters. We also explored the gender gap in a seventh area, journal productivity, because it can moderate bias in other contexts. We focused on these specific domains, in which sexism has most often been alleged to be pervasive, because they represent important types of evaluation, and the extensive research corpus within these domains provides sufficient quantitative data for comprehensive analysis. Contrary to the omnipresent claims of sexism in these domains appearing in top journals and the media, our findings show that tenure-track women are at parity with tenure-track men in three domains (grant funding, journal acceptances, and recommendation letters) and are advantaged over men in a fourth domain (hiring). For teaching ratings and salaries, we found evidence of bias against women; although gender gaps in salary were much smaller than often claimed, they were nevertheless concerning.

We synthesized the vast, contradictory scholarly literature on gender bias in academic science from 2000 to 2020. In the most prestigious journals and media outlets, which influence many people’s opinions about sexism, bias is frequently portrayed as an omnipresent factor limiting women’s progress in the tenure-track academy. Claims and counterclaims regarding the presence or absence of sexism span a range of evaluation contexts. Our approach relied on a combination of meta-analysis and analytic dissection. We evaluated the empirical evidence for gender bias in six key contexts in the tenure-track academy: (a) tenure-track hiring, (b) grant funding, (c) teaching ratings, (d) journal acceptances, (e) salaries, and (f) recommendation letters. We also explored the gender gap in a seventh area, journal productivity, because it can moderate bias in other contexts. We focused on these specific domains, in which sexism has most often been alleged to be pervasive, because they represent important types of evaluation, and the extensive research corpus within these domains provides sufficient quantitative data for comprehensive analysis. Contrary to the omnipresent claims of sexism in these domains appearing in top journals and the media, our findings show that tenure-track women are at parity with tenure-track men in three domains (grant funding, journal acceptances, and recommendation letters) and are advantaged over men in a fourth domain (hiring). For teaching ratings and salaries, we found evidence of bias against women; although gender gaps in salary were much smaller than often claimed, they were nevertheless concerning.

More here.

A meditative French surrealist poem: “I Have Dreamed of You So Much”

Friday Poem

The Beaching

The pod of whales beached themselves on Rutland Island,

chose the isolated sweep of the Back Strand to come ashore.

My grandmother in her final years would have understood.

Those long-finned pilot whales suffered some trauma,

became distressed and confused. And so for her that winter

when told her grownup daughter had died suddenly.

Three years later, hearing that her eldest had also

passed on threw something within her off-kilter.

Sent her mind homing towards the Back Strand.

The whales had wandered together, over thirty of them,

swam through Scottish waters to the Sound of Arranmore,

heading towards the crescent of shoreline and their ending.

She would have understood, the Rutland-born woman

who had long left the island but yearned for that place; called

for it constantly, rose from her sickbed in the middle of the night.

I need to go now. They will be waiting; it will soon be low tide.

She wanted to journey, follow those already gone,

float ashore, let grief beach her there on the Back Strand.

by Denise Blake

from Uimhir a Cúig | The Beaching: Poems

Numero Cinque Magazine

C.P. Cavafy: Bard Of A Lost Age

Ben Libman at Poetry Magazine:

Cavafy did not cut an imposing figure. His bearing—along with his poetry, his philosophy, and his historiographical perspective—might best be described as askew. Or, to borrow Forster’s now-famous line, he appeared as “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.” In modern parlance, we would simply call Cavafy queer. This is meant in every sense of that term but especially in its now primary sense of homosexuality—a fact at the core of Cavafy’s effect on Forster’s worldview and his understanding of art. In the words of the critic Peter Mackridge, Alexandria’s modern poet laureate embodied and defended the idea that “‘perversion’ is ‘the source of greatness’” in art as in life.

Cavafy did not cut an imposing figure. His bearing—along with his poetry, his philosophy, and his historiographical perspective—might best be described as askew. Or, to borrow Forster’s now-famous line, he appeared as “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.” In modern parlance, we would simply call Cavafy queer. This is meant in every sense of that term but especially in its now primary sense of homosexuality—a fact at the core of Cavafy’s effect on Forster’s worldview and his understanding of art. In the words of the critic Peter Mackridge, Alexandria’s modern poet laureate embodied and defended the idea that “‘perversion’ is ‘the source of greatness’” in art as in life.

Cavafy cultivated his homosexuality—its aesthetic potential and its epistemological power—in a city that, to his mind, had been the epicenter of gay sensuality going back to the time of Alexander. His poems were deeply erotic from the start, but after 1919, they unequivocally laid claim to homoeroticism.

more here.

The Art Of Rosemarie Trockel

Lynne Cooke at Artforum:

In 1988—that is, before any hallmark style threatened to dominate her practice—Trockel identified the “constants” that fueled her protean vision as “woman, inconsistency, reaction to fashionable trends.” Woman, broadly speaking, is the focus of three of the remaining four galleries on level one. Devoted mostly to the artist’s early years, the trio of dark, densely installed rooms include numerous canonical works featuring such key motifs as blown eggs, hot plates, and corporate logos. Consider Sabine, 1994, a digital print that depicts a naked brunette in sunglasses poised precariously on a small stove in a humble kitchen. Rhyming her subject’s pose with that of the Crouching Aphrodite, Trockel injects a mordant note into the misogynistic scenario. When installed at the MMK at the apex of a tall triangular gallery, Sabine literally acts out its governing thematics: constraint and confinement. The video Mr. Sun, 2000, projected on a hanging screen nearby, is more abject: As the camera crawls lasciviously over a gleaming stove, Brigitte Bardot’s voice croons, “Stay awhile, Mr. Sun.” Dominating the adjacent wall is a large knit painting, Made in Western Germany, 1987, the eponymous anglophone trademark repeated serially across its surface. Coined in 1973 to guarantee the high quality of products manufactured in the FDR (as opposed to the GDR) for an international market, the logo symbolizes the Wirtschaftswunder, the postwar economic miracle during which Trockel came of age in the Rhineland.

In 1988—that is, before any hallmark style threatened to dominate her practice—Trockel identified the “constants” that fueled her protean vision as “woman, inconsistency, reaction to fashionable trends.” Woman, broadly speaking, is the focus of three of the remaining four galleries on level one. Devoted mostly to the artist’s early years, the trio of dark, densely installed rooms include numerous canonical works featuring such key motifs as blown eggs, hot plates, and corporate logos. Consider Sabine, 1994, a digital print that depicts a naked brunette in sunglasses poised precariously on a small stove in a humble kitchen. Rhyming her subject’s pose with that of the Crouching Aphrodite, Trockel injects a mordant note into the misogynistic scenario. When installed at the MMK at the apex of a tall triangular gallery, Sabine literally acts out its governing thematics: constraint and confinement. The video Mr. Sun, 2000, projected on a hanging screen nearby, is more abject: As the camera crawls lasciviously over a gleaming stove, Brigitte Bardot’s voice croons, “Stay awhile, Mr. Sun.” Dominating the adjacent wall is a large knit painting, Made in Western Germany, 1987, the eponymous anglophone trademark repeated serially across its surface. Coined in 1973 to guarantee the high quality of products manufactured in the FDR (as opposed to the GDR) for an international market, the logo symbolizes the Wirtschaftswunder, the postwar economic miracle during which Trockel came of age in the Rhineland.

more here.