Mark Peplow in Nature:

Half a decade ago, chemist Mark Levin was a postdoc looking for a visionary project that could change his field. He found inspiration in a set of published wish lists from pharmaceutical-industry scientists who were looking for ways to transform medicinal chemistry1,2. Among their dreams, one concept stood out: the ability to precisely edit a molecule by deleting, adding or swapping single atoms in its core.

Half a decade ago, chemist Mark Levin was a postdoc looking for a visionary project that could change his field. He found inspiration in a set of published wish lists from pharmaceutical-industry scientists who were looking for ways to transform medicinal chemistry1,2. Among their dreams, one concept stood out: the ability to precisely edit a molecule by deleting, adding or swapping single atoms in its core.

This sort of molecular surgery could dramatically speed up drug discovery — and might altogether revolutionize how organic chemists design molecules. One 2018 review called it a ‘moonshot’ concept. Levin was hooked.

Now head of a team at the University of Chicago in Illinois, Levin is among a cadre of chemists pioneering these techniques, aiming to more efficiently forge new drugs, polymers and biological molecules such as peptides. In the past two years, more than 100 papers on the technique — known as skeletal editing — have been published, demonstrating its potential (see ‘Skeletal editing on the rise’). “There’s a tremendous amount of buzz right now around this topic,” says Danielle Schultz, director of discovery-process chemistry at pharmaceutical company Merck in Kenilworth, New Jersey.

More here.

Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems

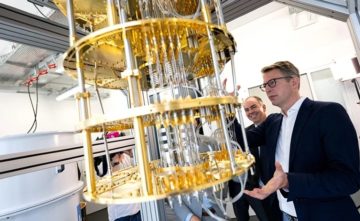

Pictures from Brueghel and Other Poems If you believe the hype, computers that exploit the strange behaviours of the atomic realm could accelerate drug discovery, crack encryption, speed up decision-making in financial transactions, improve machine learning, develop revolutionary materials and even address climate change. The surprise is that those claims are now starting to seem a lot more plausible — and perhaps even too conservative.

If you believe the hype, computers that exploit the strange behaviours of the atomic realm could accelerate drug discovery, crack encryption, speed up decision-making in financial transactions, improve machine learning, develop revolutionary materials and even address climate change. The surprise is that those claims are now starting to seem a lot more plausible — and perhaps even too conservative. In his now-classic 2018 book,

In his now-classic 2018 book,  The key to Philip’s personal appeal was his humor. As a boy, his favorite reading had been a famous joke book by a fellow Florentine, Arlotto Mainardi. As a man, Philip was quite a jester—and very jolly as well as a little zany. Writing about Philip in his Italian Journey, Goethe dubbed him “the humorous saint.”

The key to Philip’s personal appeal was his humor. As a boy, his favorite reading had been a famous joke book by a fellow Florentine, Arlotto Mainardi. As a man, Philip was quite a jester—and very jolly as well as a little zany. Writing about Philip in his Italian Journey, Goethe dubbed him “the humorous saint.” Germany Year Zero is the closest that Italian Neorealism came to reckoning with the psychic life of children. Made at the same time, Fireworks meditates on the generative possibilities of psychic and sexual shattering. In so many ways, Fireworks anticipates the explosion of the queer underground cinema that blossomed in the United States in the ’60s and in which Anger’s later film Scorpio Rising (1963) played a central role. Yet Fireworks is also a product of its own “queer time and place.”

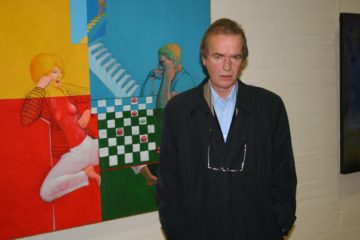

Germany Year Zero is the closest that Italian Neorealism came to reckoning with the psychic life of children. Made at the same time, Fireworks meditates on the generative possibilities of psychic and sexual shattering. In so many ways, Fireworks anticipates the explosion of the queer underground cinema that blossomed in the United States in the ’60s and in which Anger’s later film Scorpio Rising (1963) played a central role. Yet Fireworks is also a product of its own “queer time and place.” To be British is a very complicated fate. To be a British novelist can seem a catastrophe. You enter into a miasma of history and class and garbage and publication—the way a sad cow might feel entering the abattoir. Or certainly that was how I felt, twenty years ago, when I entered the abattoir myself. One allegory for this system was the glamour of Martin Amis. Everyone had an opinion on Amis, and the strangeness was that this opinion was never just on the prose, on the novels and the stories and the essays. It was also an opinion on his opinions: the party gossip and the newspaper theories, the Oxford education and the afternoon tennis.

To be British is a very complicated fate. To be a British novelist can seem a catastrophe. You enter into a miasma of history and class and garbage and publication—the way a sad cow might feel entering the abattoir. Or certainly that was how I felt, twenty years ago, when I entered the abattoir myself. One allegory for this system was the glamour of Martin Amis. Everyone had an opinion on Amis, and the strangeness was that this opinion was never just on the prose, on the novels and the stories and the essays. It was also an opinion on his opinions: the party gossip and the newspaper theories, the Oxford education and the afternoon tennis. Memories are shadows of the past but also flashlights for the future. Our recollections guide us through the world, tune our attention and shape what we learn later in life. Human and animal studies have shown that memories can alter our perceptions of future events and the attention we give them. “We know that past experience changes stuff,” said

Memories are shadows of the past but also flashlights for the future. Our recollections guide us through the world, tune our attention and shape what we learn later in life. Human and animal studies have shown that memories can alter our perceptions of future events and the attention we give them. “We know that past experience changes stuff,” said  I’m bored; you’re bored; we’re all bored. By our books and movies and television shows, the endless blandness of the Netflix queue, by our music and theater and art. Culture now is strenuously cautious, nervously polite, earnestly worthy, ploddingly obvious, and above all, dismally predictable. It never dares to stray beyond the four corners of the already known. Robert Hughes spoke of the shock of the new, his phrase for modernism in the arts. Now there’s nothing that is shocking, and nothing that is new: irresponsible, dangerous; singular, original; the child of one weird, interesting brain. Decent we have, sometimes even good: well-made, professional, passing the time. But wild, indelible, commanding us without appeal to change our lives? I don’t think we even remember what that feels like.

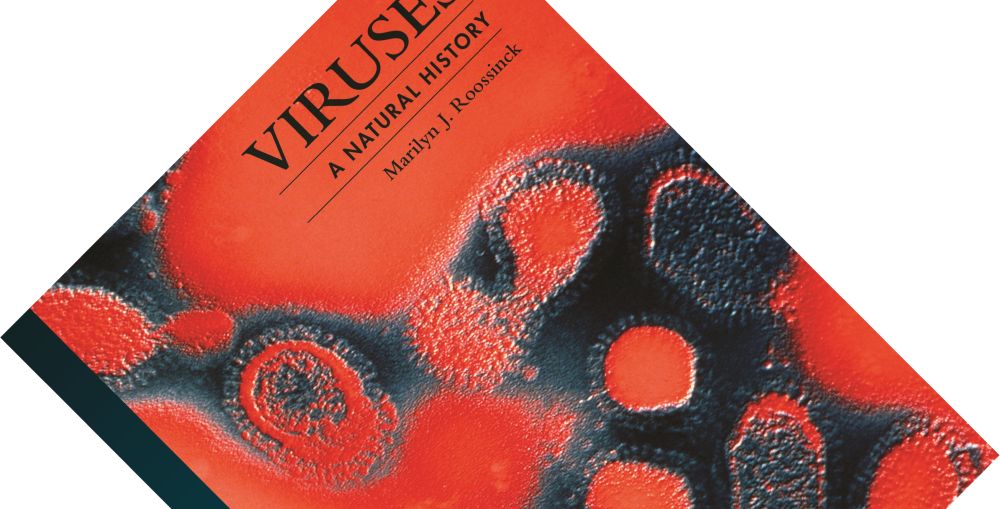

I’m bored; you’re bored; we’re all bored. By our books and movies and television shows, the endless blandness of the Netflix queue, by our music and theater and art. Culture now is strenuously cautious, nervously polite, earnestly worthy, ploddingly obvious, and above all, dismally predictable. It never dares to stray beyond the four corners of the already known. Robert Hughes spoke of the shock of the new, his phrase for modernism in the arts. Now there’s nothing that is shocking, and nothing that is new: irresponsible, dangerous; singular, original; the child of one weird, interesting brain. Decent we have, sometimes even good: well-made, professional, passing the time. But wild, indelible, commanding us without appeal to change our lives? I don’t think we even remember what that feels like. Viruses are possibly even more maligned than bacteria, spoken of exclusively in terms of disease. Here, virologist Marilyn J. Roossinck ranges far beyond human pathogens to convince you how narrow that picture is. She instead reveals them as enigmatic entities that are intimately entwined with the entirety of Earth’s biosphere, exploiting and enabling it in equal measure. Backed by numerous infographics, the book alternates between chapters on basic principles of virology and brief portraits of noteworthy viruses. The result is an entry-level introduction to virology that fascinated me more than I expected.

Viruses are possibly even more maligned than bacteria, spoken of exclusively in terms of disease. Here, virologist Marilyn J. Roossinck ranges far beyond human pathogens to convince you how narrow that picture is. She instead reveals them as enigmatic entities that are intimately entwined with the entirety of Earth’s biosphere, exploiting and enabling it in equal measure. Backed by numerous infographics, the book alternates between chapters on basic principles of virology and brief portraits of noteworthy viruses. The result is an entry-level introduction to virology that fascinated me more than I expected. “This is not a scenic drive,” said James Willcox, of adventure travel specialist

“This is not a scenic drive,” said James Willcox, of adventure travel specialist  At the press conference following the Cannes premiere of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, someone asked Robert De Niro about his character, a kingpin of a sort with a tricky psyche. “It’s the banality of evil,” he said, describing the character’s moral ambiguity. “It’s the thing we have to watch out for. We see it today, of course. We all know who I’m going to talk about, but I’m not going to say his name.” (

At the press conference following the Cannes premiere of Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, someone asked Robert De Niro about his character, a kingpin of a sort with a tricky psyche. “It’s the banality of evil,” he said, describing the character’s moral ambiguity. “It’s the thing we have to watch out for. We see it today, of course. We all know who I’m going to talk about, but I’m not going to say his name.” (