Asad Raza in The Fence:

You, a sensitive ingénue freshly arrived from the subcontinent, face the gleaming metropolis for the first time. Having hardened yourself to the feelings of your family, you have abandoned a prospective career as clerk in a lawyer’s office and a stable relationship with your third cousin, Padma, for a life of self-actualisation.

You, a sensitive ingénue freshly arrived from the subcontinent, face the gleaming metropolis for the first time. Having hardened yourself to the feelings of your family, you have abandoned a prospective career as clerk in a lawyer’s office and a stable relationship with your third cousin, Padma, for a life of self-actualisation.

A bookish sort of fellow, praised in your Commonwealth public school for your poise and intelligence, you dream of writing a novel. A proper one, full of lengthy digressions and state-of-the-nation screeds. You want to convey the psychic disruption and emotional tumult of the postcolonial condition. You suffer from double vision, blurred vision, seeing triple of everything, but one thing you do see clearly, though, is the glory. Your book will sweep the Booker, the Whitbread and any other prestigious bauble you could think of. You imagine the valley of tears from critics and fans alike, the letters of gratitude, the visiting professorships and the honorary doctorates. It’ll be the greatest novel ever written about the continent – if only you could just get past the first line.

You need a guide.

More here.

Last year

Last year  We live in an age of inequality—or so we’re frequently told. Across the globe, but especially in the wealthy economies of the West, the gap between the rich and the rest has widened year after year and become a chasm, spreading anxiety, stoking resentment, and roiling politics. It is to blame for everything from the rise of former U.S. President Donald Trump and the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom to the “yellow vest” movement in France and the recent protests of retirees in China, which has one of the world’s highest rates of income inequality. Globalization, the argument goes, may have enriched certain elites, but it hurt many other people, ravaging one-time industrial heartlands and making people susceptible to populist politics.

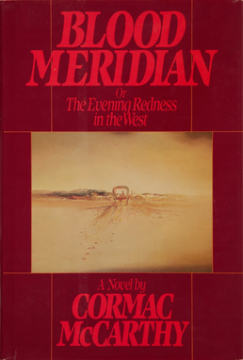

We live in an age of inequality—or so we’re frequently told. Across the globe, but especially in the wealthy economies of the West, the gap between the rich and the rest has widened year after year and become a chasm, spreading anxiety, stoking resentment, and roiling politics. It is to blame for everything from the rise of former U.S. President Donald Trump and the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom to the “yellow vest” movement in France and the recent protests of retirees in China, which has one of the world’s highest rates of income inequality. Globalization, the argument goes, may have enriched certain elites, but it hurt many other people, ravaging one-time industrial heartlands and making people susceptible to populist politics. Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian (1985) seems to me the authentic American apocalyptic novel, more relevant now than when it was written. The fulfilled renown of Moby-Dick and of As I Lay Dying is augmented by Blood Meridian, since Cormac McCarthy is the worthy disciple both of Melville and of Faulkner. I venture that no other living American novelist, not even Pynchon, has given us a book as strong and memorable as Blood Meridian, much as I appreciate his Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow, and Mason & Dixon. McCarthy himself has not matched Blood Meridian, but it is the ultimate Western, not to be surpassed.

Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian (1985) seems to me the authentic American apocalyptic novel, more relevant now than when it was written. The fulfilled renown of Moby-Dick and of As I Lay Dying is augmented by Blood Meridian, since Cormac McCarthy is the worthy disciple both of Melville and of Faulkner. I venture that no other living American novelist, not even Pynchon, has given us a book as strong and memorable as Blood Meridian, much as I appreciate his Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow, and Mason & Dixon. McCarthy himself has not matched Blood Meridian, but it is the ultimate Western, not to be surpassed. History is filled with secret heroes whose behind-the-scenes actions are essential to the exploits of public-facing heroes. Bringing these figures out of the shadows is a key role of historians. Helen Scott is one of those hidden heroines. Scott was the American film publicist, then translator, best known as

History is filled with secret heroes whose behind-the-scenes actions are essential to the exploits of public-facing heroes. Bringing these figures out of the shadows is a key role of historians. Helen Scott is one of those hidden heroines. Scott was the American film publicist, then translator, best known as  Q\ You deal with a metaphysical question in the book, about new humans.

Q\ You deal with a metaphysical question in the book, about new humans. Galit Blecher never wanted to start smoking, but during her service in the Israeli military, she succumbed. “Everyone in Israel smoked in the army,” she says. Having held out for more than one year, an especially tedious posting broke her resolve. “I was driving three hours through the desert, several times a week,” she says. “I was falling asleep.”

Galit Blecher never wanted to start smoking, but during her service in the Israeli military, she succumbed. “Everyone in Israel smoked in the army,” she says. Having held out for more than one year, an especially tedious posting broke her resolve. “I was driving three hours through the desert, several times a week,” she says. “I was falling asleep.” Ngũgĩ is a giant of African writing, and to a Kenyan writer like me he looms especially large. Alongside writers such as

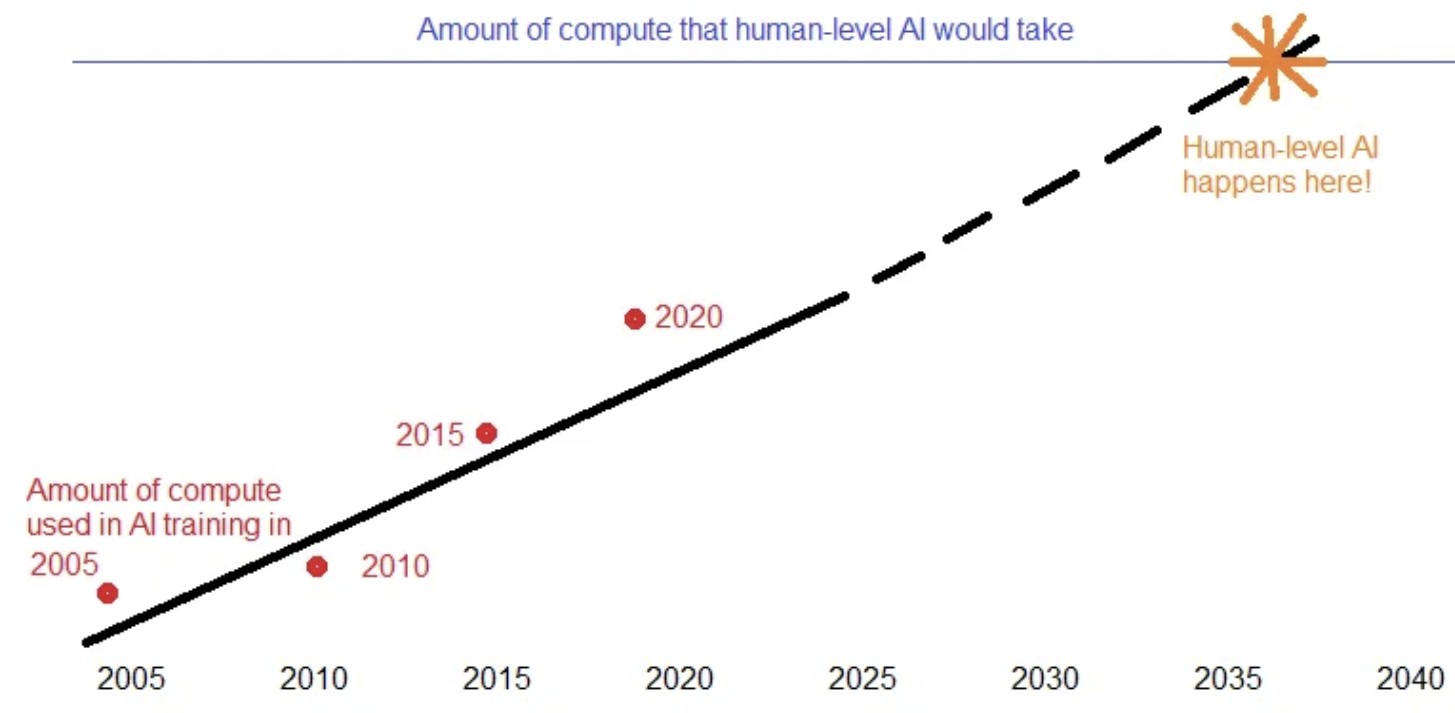

Ngũgĩ is a giant of African writing, and to a Kenyan writer like me he looms especially large. Alongside writers such as  Starting during Barack Obama’s first run for president, I began making a number of predictions that struck most people as outlandish at the time. First was the prediction, based in part on Obama’s rise,

Starting during Barack Obama’s first run for president, I began making a number of predictions that struck most people as outlandish at the time. First was the prediction, based in part on Obama’s rise,  As Americans, we find ourselves in a culture that so fetishizes success that it cannot tolerate failure. So it deals with it in one of two ways. The first is to view failure in individualized and atomized terms, blaming the losers for their losses. The second, which is equally insidious, is to be so disdainful of failure that it insists that what looks like failure in fact is a mere “stepping-stone to success,” in the philosopher Costica Bradatan’s phrase. Thus the platitudinous self-help bromides that we find adorned on a framed poster in a bank teller’s cubicle (“Failure is success in progress”) or shouted by a fitness influencer hawking protein powder on TikTok (“There’s no failure that willpower can’t turn into success”). In a culture that demands overcoming against all odds, even failure has been commodified by the American self-help industrial complex: rebranded not as a devastating and possibly life-altering event but as a blip en route to a chest-thumping achievement, accomplishment, or acquisition.

As Americans, we find ourselves in a culture that so fetishizes success that it cannot tolerate failure. So it deals with it in one of two ways. The first is to view failure in individualized and atomized terms, blaming the losers for their losses. The second, which is equally insidious, is to be so disdainful of failure that it insists that what looks like failure in fact is a mere “stepping-stone to success,” in the philosopher Costica Bradatan’s phrase. Thus the platitudinous self-help bromides that we find adorned on a framed poster in a bank teller’s cubicle (“Failure is success in progress”) or shouted by a fitness influencer hawking protein powder on TikTok (“There’s no failure that willpower can’t turn into success”). In a culture that demands overcoming against all odds, even failure has been commodified by the American self-help industrial complex: rebranded not as a devastating and possibly life-altering event but as a blip en route to a chest-thumping achievement, accomplishment, or acquisition. It’s a warm summer afternoon and you have everything set-up for a lovely afternoon in the great outdoors. You’ve got a cold drink in hand and the smell of sausages sizzling away is making you hungry. You fold out the camp chair and dust of the cobwebs, ready to chill out. Just then, the all too familiar buzz of a fly echoes in your ear. And so the onslaught begins. You swat and they just come back, gluttons for the punishment of your lazily swiping hand. Sure, they’re a nuisance. But flies get a bad rap and we’re here to try and convince you that they could in fact be seen as the true heroes of the Aussie summer.

It’s a warm summer afternoon and you have everything set-up for a lovely afternoon in the great outdoors. You’ve got a cold drink in hand and the smell of sausages sizzling away is making you hungry. You fold out the camp chair and dust of the cobwebs, ready to chill out. Just then, the all too familiar buzz of a fly echoes in your ear. And so the onslaught begins. You swat and they just come back, gluttons for the punishment of your lazily swiping hand. Sure, they’re a nuisance. But flies get a bad rap and we’re here to try and convince you that they could in fact be seen as the true heroes of the Aussie summer.