Simon Makin in Nature:

Galit Blecher never wanted to start smoking, but during her service in the Israeli military, she succumbed. “Everyone in Israel smoked in the army,” she says. Having held out for more than one year, an especially tedious posting broke her resolve. “I was driving three hours through the desert, several times a week,” she says. “I was falling asleep.”

Galit Blecher never wanted to start smoking, but during her service in the Israeli military, she succumbed. “Everyone in Israel smoked in the army,” she says. Having held out for more than one year, an especially tedious posting broke her resolve. “I was driving three hours through the desert, several times a week,” she says. “I was falling asleep.”

After returning to civilian life, she gave up smoking twice with the help of an antidepressant drug called bupropion (also known as Zyban), which reduces cravings and withdrawal, but she started smoking again each time. Then, six years ago, she joined a clinical trial of a new treatment targeted at people who had tried and failed to quit smoking. She hasn’t smoked since. “After Zyban, there was always a craving when I saw other smokers,” Blecher says. “This time it’s a real aversion; I can’t stand smelling cigarettes.”

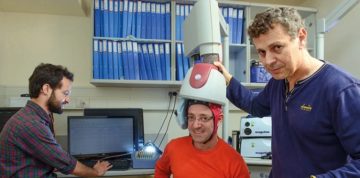

The treatment that helped Blecher is called repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and uses magnetic fields to stimulate regions of the brain involved in addiction. The effect on quit rates in the trial was modest, but comparable to bupropion, which blocks nicotine receptors in the brain. It was enough to convince the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve, in August 2020, the use of repetitive TMS to help people quit smoking.

More here.