Category: Recommended Reading

Sunday Poem

Introduction to Poetry

I ask them to take a poem

and hold it up to the light

like a color slide

or press an ear against its hive.

I say drop a mouse into a poem

and watch him probe his way out,

or walk inside the poem’s room

and feel the walls for a light switch.

I want them to waterski

across the surface of a poem

waving at the author’s name on the shore.

But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

by Billy Collins

from The Apple That Astonished Paris

Robert Black (1956 – 2023) Double Bassist

Julian Sands (1958 – 2023) Actor

Bobby Osborne (1931 – 2023) Bluegrass Musician

Saturday, July 1, 2023

Congress Redux?

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

On 7 September last year, the senior Congress leader Rahul Gandhi launched Bharat Jodo Yatra, a protest march to ‘unite India’ against the ‘divisive politics’ of the BJP-led government. Stretching from Kanyakumari, on the southern tip of India, to Jammu and Kashmir in the north, the yatra covered some 3,500 kilometers and twelve states. A number of celebrities made headlines by joining this five-month journey. As did Gandhi’s outfit (a single polo T-shirt throughout the winter), his scraggly beard and his fitness regime (‘fourteen pushups in ten seconds’). The right-wing backlash was predictable: some mocked Gandhi’s Burberry wardrobe, others likened his facial hair to Saddam Hussein’s. Yet, in every state he crossed, the 52-year-old scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty saw his approval ratings increase – most of all in Delhi, where they jumped from 32% to 55%. Riding a wave of mass popularity for the first time in his career, Gandhi provided this memorable summation: ‘In the bazaar of hate, I am opening shops of love’. And then, within a few weeks, his star plummeted. On 23 March, a lower Indian court convicted him of making defamatory comments about the surname of the Prime Minister. A day later, he was summarily ejected from parliament.

While Gandhi’s political future is in jeopardy, his nemesis still appears to be untouchable, despite the volatility of his period in office. Over nine years, Narendra Modi has unleashed a devastating series of ‘shock and awe’ operations which have consistently failed to dent his popularity. In November 2016, he withdrew 86% of the circulating currency overnight, costing 10-12 million workers their jobs.

More here.

The myth of mirrored twins

Gavin Evansi in Aeon:

Gavin Evansi in Aeon:

Thirteen days before the start of the Second World War, a 35-year-old unmarried immigrant woman gave birth slightly prematurely to identical twins at the Memorial Hospital in Piqua, Ohio and immediately put them up for adoption. The boys spent their first month together in a children’s home before Ernest and Sarah Springer adopted one – and would have adopted both had they not been told, incorrectly, that the other twin had died. Two weeks later, Jess and Lucille Lewis adopted the other baby and, when they signed the papers at the local courthouse, calling their boy James, the clerk remarked: ‘That’s what [the Springers] named their son.’ Until then they hadn’t known he was a twin.

The boys grew up 40 miles apart in middle-class Ohioan families. Although James Lewis was six when he learnt he’d been adopted, it was only in his late 30s that he began searching for his birth family at the Ohio courthouse. In 1979, the adoption agency wrote to James Springer, who was astonished by the news, because as a teenager he’d been told his twin had died at birth. He phoned Lewis and four days later they met – a nervous handshake and then beaming smiles. Reports on their case prompted a Minneapolis-based psychologist, Thomas Bouchard, to contact them, and a series of interviews and tests began. The Jim Twins, as they were known, became Bouchard’s star turn.

Both Jims, it transpired, had worked as deputy sheriffs, and had done stints at McDonald’s and at petrol stations; they’d both taken holidays at Pass-a-Grille beach in Florida, driving there in their light-blue Chevrolets. Each had dogs called Toy and brothers called Larry, and they’d married and divorced women called Linda, then married Bettys. They’d called their first sons James Alan/Allan. Both were good at maths and bad at spelling, loved carpentry, chewed their nails, chain-smoked Salem and drank Miller Lite beer. Both had haemorrhoids, started experiencing migraines at 18, gained 10 lb in their early 30s, and had similar heart problems and sleep patterns.

More here.

The Localist

Jonathan Levy in Boston Review:

Jonathan Levy in Boston Review:

One puzzle in the intellectual history of the twentieth century is why the University of Chicago became the leading bastion of free market economics.

Scholars have proposed compelling explanations, from the strong rooting of “price theory” at Chicago by the end of the 1930s to the participation of many of its faculty members in postwar, pro-market advocacy groups that began to embrace neoliberalism by the 1960s. But having spent most of my adult life at the university and in its surrounding neighborhood of Hyde Park, I can’t help but wonder about a more quotidian contributing factor: the area’s limited range of commerce in the days when Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, and George Stigler walked these streets.

Hyde Park is on Chicago’s South Side, not the posh North. The area once buzzed with urban commercial traffic—right after World War II, when many Black people moved to the city from the South in order to work in factories. Famous jazz and blues clubs abounded on the neighborhood’s central commercial corridor of 55th street, where legends like Coleman Hawkins, Art Blakey, Thelonious Monk, and Sonny Rollins played. But then the factories began to shutdown. Poverty and street crime rose. The U.S. “urban crisis” fell on Chicago.

At the university, fears arose about white flight and a potential diminished ability to recruit students and faculty. Thus began a decades-long “urban renewal” project in Hyde Park, carried out by the city and the university.

More here.

On marriage, Netflix and other things I hate

Devorah Baum in The White Review:

1. ‘It’s kind of crazy to shop at Target, watch Netflix, drive a Honda, and still have a husband.’

1. ‘It’s kind of crazy to shop at Target, watch Netflix, drive a Honda, and still have a husband.’

Marriage falls into a specific category of things I don’t want to think about because their meaning swells the more you do. Personally, socially, historically. And yet, I am always interested in love stories: I listen to my friends talk about their love lives and when they apologise for dwelling on something – ‘is this boring?!’ – I answer, ‘love is the subject.’ I am interested in how we organise our lives by connection with other people, in how we live alongside others, in how love is a social construct and a form of relation. Love is the subject, by which I mean, love is something we want to narrate and discuss, because words make this inexplicable and incomprehensible thing – other people – feel less ambiguous, perhaps closer to certainty.

I don’t mean to conflate marriage and love. Quite the opposite – it is marriage’s function as an organising logic that I fear, that I believe does not work for anyone (especially not women). When I speak of marriage, it is not love I think of, but power. I think about Phyllis Rose discussing this in the introduction to PARALLEL LIVES: FIVE VICTORIAN MARRIAGES (1983): ‘When we resign power or assume new power, we insist it is not happening and demand to be talked to about love. Perhaps that is what love is – the momentary or prolonged refusal to think of another person in terms of power.’ But power is impossible to sidestep. A page later: ‘Who can resist the thought that love is the ideological bone thrown to women to distract their attention from the powerlessness of their lives?’

More here.

Post-Anthropocene Humanism

Nathan Gardels at Noema:

The controversies of late over the perils and promise of generative AI have raised anew the philosophical question of where technological sovereignty ends and human autonomy begins. Will the super-intelligent capacities of the putative servant we have invented end up being our actual master?

The controversies of late over the perils and promise of generative AI have raised anew the philosophical question of where technological sovereignty ends and human autonomy begins. Will the super-intelligent capacities of the putative servant we have invented end up being our actual master?

“The fact is that the powers which seem to use and govern technology are in reality more or less unwittingly used and governed by it,” Giorgio Agamben, the philosopher of biopolitics, observed in his presentation to the opening symposium of the Berggruen Institute Europe in Venice. “Both totalitarian and democratic regimes share the same incapability to govern technology, and both end up transforming themselves through the technologies they believed they were using for their own purposes. Why does it seem so hard and even impossible to govern technology?” he asked.

more here.

What We Get Wrong About Drugs Like Ozempic

Yoni Freedhoff in Time:

Imagine a new medication was developed that not only provided meaningful improvement for the debilitating chronic condition it’s prescribed, but also helps to treat and prevent a myriad of other serious diseases. Imagine this same drug markedly improved a person’s quality of life with noted reductions in pain and improvements in mobility along with increases in confidence and mood. Now imagine that the media and medical coverage of its release are almost uniformly negative or sensationalistic.

Imagine a new medication was developed that not only provided meaningful improvement for the debilitating chronic condition it’s prescribed, but also helps to treat and prevent a myriad of other serious diseases. Imagine this same drug markedly improved a person’s quality of life with noted reductions in pain and improvements in mobility along with increases in confidence and mood. Now imagine that the media and medical coverage of its release are almost uniformly negative or sensationalistic.

This is precisely what has happened with the new generation of anti-obesity medications, that began with Wegovy/Ozempic and with many more rapidly on their way. Currently approved medications lead people with obesity to lose on average 15% of their body weight which in turn has dramatic benefits for multiple weight responsive medical conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, GERD, fatty liver disease, and more. Clinical trials of newer molecules demonstrate even greater losses with the most recent, for Retatrutide, demonstrating a 24% body weight loss after 48 weeks of use and where weight in those participants appeared to still be dropping. Sustained weight loss has been shown to decrease the risk of developing those same conditions as well as some of our most common cancers including breast, uterine, and colon.

More here.

Saturday Poem

anyone lived in a pretty how town

(with up so floating many bells down)

spring summer autumn winter

he sang his didn’t he danced his did

Women and men (both little and small)

cared for anyone not at all

they sowed their isn’t they reaped their same

sun moon stars rain

children guessed (but only a few

and down they forgot as up they grew

autumn winter spring summer)

that noone loved him more by more

when by now and tree by leaf

she laughed his joy she cried his grief

bird by snow and stir by still

anyone’s any was all to her

someones married their everyones

laughed their cryings and did their dance

(sleep wake hope and then) they

said their nevers and slept their dream

stars rain sun moon

(and only the snow can begin to explain

how children are apt to forget to remember

with up so floating many bells down)

one day anyone died i guess

(and noone stooped to kiss his face)

busy folk buried them side by side

little by little and was by was

all by all and deep by deep

and more by more they dream their sleep

noone and anyone earth by april

wish by spirit and if by yes.

Women and men (both dong and ding)

summer autumn winter spring

reaped their sowing and went their came

sun moon stars rain

by e.e.cummings

from 50 poems

Hawthorne Books, 1940

Friday, June 30, 2023

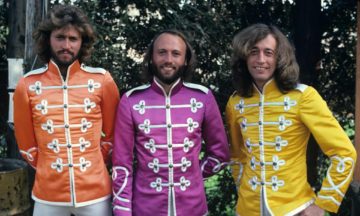

Bee Gees: Children of the World

Andrew Martin in The Guardian:

This book contains few new interviews about the “insanely productive” group who sold more than 220m records: it is author-led, meaning we are mainly given Bob Stanley’s opinions about the Bee Gees’ music. But there are few people whose opinions I would rather have. Stanley is a highly articulate proponent of pop rather than rock (his previous book was Let’s Do It: The Birth of Pop) and a practitioner himself, with his group Saint Etienne.

This book contains few new interviews about the “insanely productive” group who sold more than 220m records: it is author-led, meaning we are mainly given Bob Stanley’s opinions about the Bee Gees’ music. But there are few people whose opinions I would rather have. Stanley is a highly articulate proponent of pop rather than rock (his previous book was Let’s Do It: The Birth of Pop) and a practitioner himself, with his group Saint Etienne.

Pop has come in out of the cold in recent years, Blondie as likely to be pontificated about as Led Zeppelin, but the Bee Gees – who were certainly “pop”, despite evolving through quasi-psychedelia into R&B and disco – remain, as Stanley writes, “othered”, rarely accorded the respect they deserve. And he suggests that such praise as they do receive tends to be conditional: “It’s the Bee Gees… but it’s really good.”

More here.

Untangling quantum entanglement

Huw Price and Ken Wharton in Aeon:

Almost a century ago, physics produced a problem child, astonishingly successful yet profoundly puzzling. Now, just in time for its 100th birthday, we think we’ve found a simple diagnosis of its central eccentricity.

Almost a century ago, physics produced a problem child, astonishingly successful yet profoundly puzzling. Now, just in time for its 100th birthday, we think we’ve found a simple diagnosis of its central eccentricity.

This weird wunderkind was ‘quantum mechanics’ (QM), a new theory of how matter and light behave at the submicroscopic level. Through the 1920s, QM’s components were assembled by physicists such as Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. Alongside Albert Einstein’s relativity theory, it became one of the two great pillars of modern physics.

The pioneers of QM realised that the new world they had discovered was very strange indeed, compared with the classical (pre-quantum) physics they had all learned at school. These days, this strangeness is familiar to physicists, and increasingly useful for technologies such as quantum computing.

The strangeness has a name – it’s called entanglement – but it is still poorly understood. Why does the quantum world behave this strange way? We think we’ve solved a central piece of this puzzle.

More here.

Canada has a nation-building population strategy. Does America?

Noah Smith in Noahpinion:

A lot of people — at least, a lot of people who read this blog — know of Matt Yglesias’ book One Billion Americans. It’s good, you should read it. But not as many seem to know that it’s actually a riff on a book that came out three years earlier called Maximum Canada: Why 35 Million Canadians Are Not Enough, by Doug Saunders. In fact, the books are pretty different; Saunders spends most of his time justifying the idea of a bigger Canada with appeals to the country’s history, culture, and politics, where Yglesias mostly discusses the practical details of how we’d fit the newcomers into the country.

A lot of people — at least, a lot of people who read this blog — know of Matt Yglesias’ book One Billion Americans. It’s good, you should read it. But not as many seem to know that it’s actually a riff on a book that came out three years earlier called Maximum Canada: Why 35 Million Canadians Are Not Enough, by Doug Saunders. In fact, the books are pretty different; Saunders spends most of his time justifying the idea of a bigger Canada with appeals to the country’s history, culture, and politics, where Yglesias mostly discusses the practical details of how we’d fit the newcomers into the country.

But what these two books share is that they’re both advocating a certain type of nation-building strategy — the idea of deliberately promoting large-scale immigration in order to expand a country’s population toward a numerical target. This isn’t something the U.S. has really done in the past.

More here.

Good News!

Hugh Kenner’s Theory of Action

Todd Cronan at nonsite:

According to Kenner, the Hollow Men provides the first expression of the “structural principle” of Eliot’s later work and, I would suggest, of Kenner’s work as well. What is that principle? Eliot’s aim is to articulate “moral states which to an external observer are indistinguishable from one another” (IP, 163). So that we can “judge a man’s action,” Kenner says, but “we cannot judge the man by his actions.” What Kenner calls “distinct actions,” occlude from the observer the nature of a man’s true actions. And since what we are asked to judge are “moral states,” it naturally follows that we are not meant to judge works of art, which is exactly what Kenner says (IP, 163). “In art,” Kenner writes, “actions are determined by their objects.” In morals, by contrast, actions are “determined by their motives, which are hidden: hidden, often, from the actor” (IP, 163). The art that Kenner admires is anti-art in the sense that conventional artworks are construed as the expression of distinct actions, a kind of action we sometimes define as intentional tout court.

According to Kenner, the Hollow Men provides the first expression of the “structural principle” of Eliot’s later work and, I would suggest, of Kenner’s work as well. What is that principle? Eliot’s aim is to articulate “moral states which to an external observer are indistinguishable from one another” (IP, 163). So that we can “judge a man’s action,” Kenner says, but “we cannot judge the man by his actions.” What Kenner calls “distinct actions,” occlude from the observer the nature of a man’s true actions. And since what we are asked to judge are “moral states,” it naturally follows that we are not meant to judge works of art, which is exactly what Kenner says (IP, 163). “In art,” Kenner writes, “actions are determined by their objects.” In morals, by contrast, actions are “determined by their motives, which are hidden: hidden, often, from the actor” (IP, 163). The art that Kenner admires is anti-art in the sense that conventional artworks are construed as the expression of distinct actions, a kind of action we sometimes define as intentional tout court.

more here.

Incredible Minds: The Collective Intelligence of Cells During Morphogenesis with Dr. Michael Levin

Tasmanian Devils Face Threats from Rapidly Evolving Facial Cancers

Natalia Mesa in The Scientist:

Tasmanian devil populations have dwindled in recent decades due to two contagious facial cancers that cause debilitating growths. Now, alongside an international group of scientists and organizations, researchers from University of Cambridge conducted a large genetic sequencing study published in Science, and found that one of those cancers is evolving at an alarming pace and may pose a grave threat to Tasmania’s top carnivore.1 This study is the first to track the evolution of the two cancers, creating a detailed account of when the cancers arose, how they spread across the landscape, and importantly, which mutations helped them spread over time.

Tasmanian devil populations have dwindled in recent decades due to two contagious facial cancers that cause debilitating growths. Now, alongside an international group of scientists and organizations, researchers from University of Cambridge conducted a large genetic sequencing study published in Science, and found that one of those cancers is evolving at an alarming pace and may pose a grave threat to Tasmania’s top carnivore.1 This study is the first to track the evolution of the two cancers, creating a detailed account of when the cancers arose, how they spread across the landscape, and importantly, which mutations helped them spread over time.

Carolyn Hogg, a biologist at the University of Sydney who was not involved in the study, said that the research team has generated useful tools to study the devils. “You can make massive headway into understanding how the species [and] disease move through the landscape, and how the disease mutates and changes,” with genomic data, she said.

Devilish diseases

Tasmanian devils are the world’s largest carnivorous marsupials, native to only Tasmania, an island off the coast of southeast Australia. For more than 30 years, these marsupials have been battling two deadly facial cancers, devil facial tumor 1 (DFT1) and devil facial tumor 2 (DFT2). A unique feature of these cancers is that they primarily spread through biting, a common occurrence in devils during fights over mates and food. Transmissible tumors are exceedingly rare in nature, making the devils important models for studying cancer evolution.

More here.

The Sounds Of Invisible Worlds

Karen Bakker at Noema:

For millennia, the movements of the celestial bodies in the heavens above, from shining planets to the faintest of stars, have provided practical guidance to navigators and spiritual direction to oracles. But some signals created by the stars are invisible to the naked human eye.

For millennia, the movements of the celestial bodies in the heavens above, from shining planets to the faintest of stars, have provided practical guidance to navigators and spiritual direction to oracles. But some signals created by the stars are invisible to the naked human eye.

Astrophysicists have developed techniques to convert data from light signals into digital audio, using pitch, duration and other properties of sound. Wanda Díaz-Merced, a blind astronomer, sonifies plasma patterns in the upper reaches of the Earth’s atmosphere and invented new methods to detect subtle signals in the presence of visual noise. But the conversion of data into acoustic signals — called sonification — is now being used by scientists who are not vision-impaired because listening to the stars helps detect patterns that may be missed by visual representations.

more here.