Category: Recommended Reading

What an Owl Knows

Simon Worrall at The Guardian:

The book is not just about owls, though, but about the people who study them. There are many scientists and conservationists, who have, like Ackerman, fallen under the spell of these endearing creatures. People like José Luis Peña, a neuroscientist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in New York, who has discovered that a barn owl’s sound localisation system relies on sophisticated mathematical computations to pinpoint its prey. Or zoomusicologist Magnus Robb, who studies hoots.

The book is not just about owls, though, but about the people who study them. There are many scientists and conservationists, who have, like Ackerman, fallen under the spell of these endearing creatures. People like José Luis Peña, a neuroscientist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, in New York, who has discovered that a barn owl’s sound localisation system relies on sophisticated mathematical computations to pinpoint its prey. Or zoomusicologist Magnus Robb, who studies hoots.

“If anyone knows anything about anything,” Winnie-the-Pooh famously remarked, “it’s Owl who knows something about something.” And it turns out, owls know a lot. Equipped with super-sensitive hearing, great grey owls in the far north are capable of detecting and catching voles deep beneath the snow by sound alone. Scientists have even discovered that owls process sound in the visual centre of their brains, so they may actually get a “picture” of the environment they are hearing.

more here.

Effing Philosophy

Jennifer Szalai at the NY Times:

When setting out to write “A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy and War at Oxford, 1900-1960,” Nikhil Krishnan certainly had his work cut out for him. How to generate excitement for a “much-maligned” philosophical tradition that hinges on finicky distinctions in language? Whose main figures were mostly well-to-do white men, routinely caricatured — and not always unfairly — for being suspicious of foreign ideas and imperiously, insufferably smug?

When setting out to write “A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy and War at Oxford, 1900-1960,” Nikhil Krishnan certainly had his work cut out for him. How to generate excitement for a “much-maligned” philosophical tradition that hinges on finicky distinctions in language? Whose main figures were mostly well-to-do white men, routinely caricatured — and not always unfairly — for being suspicious of foreign ideas and imperiously, insufferably smug?

Krishnan, a philosopher at Cambridge, confesses up front that he, too, felt frustrated and resentful when he first encountered “linguistic” or “analytic” philosophy as a student at Oxford. He had wanted to study philosophy because he associated it with mysterious qualities like “depth” and “vision.” He consequently assumed that philosophical writing had to be densely “allusive”; after all, it was getting at something “ineffable.” But his undergraduate tutor, responding to Krishnan’s muddled excuse for some muddled writing, would have none of it. “On the contrary, these sorts of things are entirely and eminently effable,” the tutor said. “And I should be very grateful if you’d try to eff a few of them for your essay next week.”

more here.

Nikhil Krishnan on the History and Future of Analytic Philosophy

Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century – charming, genre-defying study

William Dalrymple in The Guardian:

The sudden rise of India over the past few years has taken many western observers by surprise. The Indian economy has quadrupled in size in a generation. Its ancient reputation as a centre for mathematics and scientific skills remains intact, and Indian software engineers increasingly dominate Silicon Valley. India now has the largest population in the world and is clearly on its way to becoming the third economic superpower. Its economy overtook the UK last autumn and will overtake Germany and Japan within the next decade. The only questions are whether it is the US, China or India that will dominate the world by the end of this century, and what sort of India that will be.

The sudden rise of India over the past few years has taken many western observers by surprise. The Indian economy has quadrupled in size in a generation. Its ancient reputation as a centre for mathematics and scientific skills remains intact, and Indian software engineers increasingly dominate Silicon Valley. India now has the largest population in the world and is clearly on its way to becoming the third economic superpower. Its economy overtook the UK last autumn and will overtake Germany and Japan within the next decade. The only questions are whether it is the US, China or India that will dominate the world by the end of this century, and what sort of India that will be.

Little of this would have surprised our ancestors who first sailed to India with the East India Company at the time of Shakespeare. India then had a population of around 150 million – about a fifth of the world’s total – and was producing about a quarter of global manufacturing; indeed, in many ways it was the world’s industrial powerhouse and the leader in manufactured textiles. The idea that India was ever a poor, famine-struck country is a relatively recent one, dating only from the period of British rule: historically, South Asia was always famous as the richest region of the globe, whose fertile soils gave two harvests a year and whose mines groaned with mineral riches.

More here.

Seven Amazing Accomplishments the James Webb Telescope Achieved in Its First Year

Dan Falk in Smithsonian:

The James Webb Space Telescope, the largest and most sophisticated space observatory ever built, has been sending back images and data for almost a full year now—and in that time it has delivered a treasure trove of information about everything from stars and planetary systems in our own galactic neighborhood to distant galaxies that formed when the universe was a tiny fraction of its current age. Webb has also sent back stunning images that surpass those garnered by its famous predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope.

The James Webb Space Telescope, the largest and most sophisticated space observatory ever built, has been sending back images and data for almost a full year now—and in that time it has delivered a treasure trove of information about everything from stars and planetary systems in our own galactic neighborhood to distant galaxies that formed when the universe was a tiny fraction of its current age. Webb has also sent back stunning images that surpass those garnered by its famous predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope.

Webb and Hubble are quite different instruments. For starters, while Hubble is primarily sensitive to visible light, Webb records infrared light that’s invisible to the unaided eye. These longer wavelengths of light pass through clouds of gas and dust that block visible light, letting the telescope peer past such obstacles. It also has a size advantage: While Hubble’s main mirror is 8 feet across, Webb employs an array of 18 small hexagonal mirrors that function like a single mirror 21 feet across.

More here.

Thursday, July 6, 2023

Don DeLillo’s Cold War

Siddhartha Deb in The Nation:

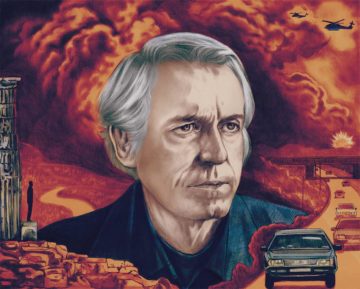

An assassin works from a partial understanding of the world. If not literally a hashishi, as suggested by the word’s etymology, an assassin must nevertheless see the world in tunnel vision, his victim viewed through the lens of a scope. The vast, complex network of humanity to which he and his victim belong, with contending narratives and blurred individual motives, cannot be allowed to exist. To do so would be to fail as an assassin.

An assassin works from a partial understanding of the world. If not literally a hashishi, as suggested by the word’s etymology, an assassin must nevertheless see the world in tunnel vision, his victim viewed through the lens of a scope. The vast, complex network of humanity to which he and his victim belong, with contending narratives and blurred individual motives, cannot be allowed to exist. To do so would be to fail as an assassin.

A Don DeLillo novel grasps both the assassin’s monomania and the contradictory, counterintuitive world of which it is a part. It is capable of displaying fidelity to both perspectives, brushing one against the other to edge its way toward a fictional truth that neither can uncover on its own. Six novels published in the 1970s established this principle, but the approach truly came into its own only with Libra (1988), DeLillo’s ninth novel. “Hashish. Interesting, interesting word,” a character says to Lee Harvey Oswald as the novel uncoils toward its climactic moment in Dallas with the Kennedy assassination. “Arabic. It’s the source of the word assassin.”

More here.

Nature, Toothless and Declawed

Clare Coffey in The New Atlantis:

We cannot be sure what animals are, because we cannot be sure what we are. We are beasts among beasts, and something qualitatively different. The boundary between these two kinds of being is always ready to dissolve by moonlight.

We cannot be sure what animals are, because we cannot be sure what we are. We are beasts among beasts, and something qualitatively different. The boundary between these two kinds of being is always ready to dissolve by moonlight.

But that boundary feels bright and clean in Martha Nussbaum’s latest rationalizing project, Justice for Animals, even if she draws it in a different place. The book is an intriguing attempt to find a simultaneously comprehensive and minimally metaphysically committed account of what we owe animals. It is also a plea, with dramatic upshots on questions like the justice of humans eating animals — even the justice of animals eating animals.

More here.

On Race and Academia

John McWhorter in the New York Times:

The Supreme Court last week outlawed the use of race-based affirmative action in college admissions. That practice was understandable and even necessary 60 years ago. The question I have asked for some time was precisely how long it would be required to continue. I’d personally come to believe that preferences focused on socioeconomic factors — wealth, income, even neighborhood — would accomplish more good while requiring less straightforward unfairness.

The Supreme Court last week outlawed the use of race-based affirmative action in college admissions. That practice was understandable and even necessary 60 years ago. The question I have asked for some time was precisely how long it would be required to continue. I’d personally come to believe that preferences focused on socioeconomic factors — wealth, income, even neighborhood — would accomplish more good while requiring less straightforward unfairness.

But many good-faith people believed, and continue to believe, that it is a clear boon to society for universities to explicitly take race into account. The arguments for and against have been made often, sometimes by me, so here I’d like to do something a little bit different.

More here.

David Albert & Sean Carroll: Quantum Theory, Boltzmann Brains, & The Fine-Tuned Universe

All possible worlds

Timothy Andersen in aeon:

Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887), Friedrich Nietzsche said: ‘Man, the bravest animal and most prone to suffer, does not deny suffering as such: he wills it, he even seeks it out, provided he is shown a meaning for it, a purpose of suffering.’ A life apparently perfect but devoid of meaning, no matter how comfortable, is a kind of hell.

Every life contains pain. Even the perfect life, the life where you have everything you want, hides its own unique struggles. Writing in The Genealogy of Morals (1887), Friedrich Nietzsche said: ‘Man, the bravest animal and most prone to suffer, does not deny suffering as such: he wills it, he even seeks it out, provided he is shown a meaning for it, a purpose of suffering.’ A life apparently perfect but devoid of meaning, no matter how comfortable, is a kind of hell.

In our search for meaning, we fantasise about the roads not taken, and these alternative lives take on a reality of their own, and, perhaps, they are real. In his novel The Midnight Library (2020), Matt Haig explores this concept. In it, a woman named Nora Seed is given the chance to live the lives she would have lived had she made different choices. Each life is a book in an infinite library. Opening the book takes her to live in that other world for as long as she feels comfortable there. Each possible world becomes a reality.

More here.

God and Evil with Yujin Nagasawa

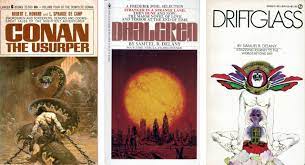

How Samuel R. Delany Reimagined Sci-Fi, Sex, and the City

Julian Lucas at The New Yorker:

In the stellar neighborhood of American letters, there have been few minds as generous, transgressive, and polymathically brilliant as Samuel Delany’s. Many know him as the country’s first prominent Black author of science fiction, who transformed the field with richly textured, cerebral novels like “Babel-17” (1966) and “Dhalgren” (1975). Others know the revolutionary chronicler of gay life, whose autobiography, “The Motion of Light in Water” (1988), stands as an essential document of pre-Stonewall New York. Still others know the professor, the pornographer, or the prolific essayist whose purview extends from cyborg feminism to Biblical philology.

In the stellar neighborhood of American letters, there have been few minds as generous, transgressive, and polymathically brilliant as Samuel Delany’s. Many know him as the country’s first prominent Black author of science fiction, who transformed the field with richly textured, cerebral novels like “Babel-17” (1966) and “Dhalgren” (1975). Others know the revolutionary chronicler of gay life, whose autobiography, “The Motion of Light in Water” (1988), stands as an essential document of pre-Stonewall New York. Still others know the professor, the pornographer, or the prolific essayist whose purview extends from cyborg feminism to Biblical philology.

There are so many Delanys that it’s difficult to take the full measure of his influence. Reading him was formative for Junot Díaz and William Gibson; Octavia Butler was, briefly, his student in a writing workshop. Jeremy O. Harris included Delany as a character in his play “Black Exhibition,” while Neil Gaiman, who is adapting Delany’s classic space adventure “Nova” (1968) as a series for Amazon, credits him with building a critical foundation not only for science fiction but also for comics and other “paraliterary” genres.

more here.

The Biologist Blowing Our Minds

George Musser in Nautilus:

Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, has a knack for taking an unassuming organism and showing it’s capable of the darnedest things. He and his team once extracted skin cells from a frog embryo and cultivated them on their own. With no other cell types around, they were not “bullied,” as he put it, into forming skin tissue. Instead, they reassembled into a new organism of sorts, a “xenobot,” a coinage based on the Latin name of the frog species, Xenopus laevis. It zipped around like a paramecium in pond water. Sometimes it swept up loose skin cells and piled them until they formed their own xenobot—a type of self-replication. For Levin, it demonstrated how all living things have latent abilities. Having evolved to do one thing, they might do something completely different under the right circumstances.

Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, has a knack for taking an unassuming organism and showing it’s capable of the darnedest things. He and his team once extracted skin cells from a frog embryo and cultivated them on their own. With no other cell types around, they were not “bullied,” as he put it, into forming skin tissue. Instead, they reassembled into a new organism of sorts, a “xenobot,” a coinage based on the Latin name of the frog species, Xenopus laevis. It zipped around like a paramecium in pond water. Sometimes it swept up loose skin cells and piled them until they formed their own xenobot—a type of self-replication. For Levin, it demonstrated how all living things have latent abilities. Having evolved to do one thing, they might do something completely different under the right circumstances.

Not long ago I met Levin at a workshop on science, technology, and Buddhism in Kathmandu. He hates flying but said this event was worth it. Even without the backdrop of the Himalayas, his scientific talk was one of the most captivating I’ve ever heard. Every slide introduced some bizarre new experiment. Butterflies retain memories from when they were caterpillars, even though their brains turned to mush in the chrysalis. Cut off the head and tail of a planarian, or flatworm, and it can grow two new heads; if you amputate again, the worm will regrow both heads.

More here.

The Cult Of David Keenan

Francisco Garcia at The New Staesman:

Memorial Device captures the glorious, drug-infused chaos of the Eighties post-punk scene in the small towns in North Lanarkshire, near Glasgow. With a vast array of characters – a revolving cast of freaks, dreamers, and burned-out, pissed-up or long-dead visionaries – Keenan depicts a time and place that existed, and the lingering reverberations of a legendary band that didn’t. “It’s not easy being Iggy Pop in Airdrie,” one character opines.

Subsequent novels by Keenan have since arrived at a dizzying pace. First came the Gordon Burn prize-winning For the Good Times (2019), an unhinged tale narrated by Sammy, an incarcerated IRA foot soldier who recalls the exhilarating anarchy of his life in 1970s Belfast. This was followed Xstabeth (2020), a ghostly continent-striding coming-of-age story, of sorts. Monument Maker (2021) was something else entirely, an uncompromising, 800-page postmodern epic, which seemed to record the full David Keenan cosmology.

more here.

Thursday Poem

The First Day’s Night Had Come

The first Day’s Night had come—

And grateful that a thing

So terrible—had been endured—

I told my Soul to sing—

She said her Strings were snapt—

Her Bow—to Atoms blown—

And so to mend her—gave me work

Until another Morn—

And then—A day as huge

As Yesterdays in pairs,

Unrolled its horror in my face—

Until it blocked my eyes—

My Brain—begun to laugh—

I mumbled—like a fool—

And tho’ tis years ago—that Day—

My Brain keeps giggling—still.

And Something’s odd—within—

That person that I was—

And this One—do not feel the same—

Could it be Madness—this?

by Emily Dickinson

from The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson

Little, Brown and Company,1960

Wednesday, July 5, 2023

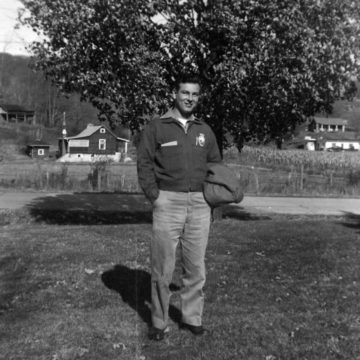

Obituary for a Quiet Life

Jeremy B. Jones in The Bitter Southerner:

When the notable figures of our day pass away, they wind up on our screens, short clips documenting their achievements, talking heads discussing their influence. The quiet lives, though, pass on soundlessly in the background. And yet those are the lives in our skin, guiding us from breakfast to bed. They’re the lives that have made us, that keep the world turning.

When the notable figures of our day pass away, they wind up on our screens, short clips documenting their achievements, talking heads discussing their influence. The quiet lives, though, pass on soundlessly in the background. And yet those are the lives in our skin, guiding us from breakfast to bed. They’re the lives that have made us, that keep the world turning.

They’re taking out the trash before we notice and walking up the road to see if the mail’s come. They’re showing us how to lay out the biscuit dough at just the right thickness. They took our sons up on the tractor on spring afternoons. They helped the neighbor with the busted sink. They jumped in the river to pull an 18-month-old out. They caught the man who’d been pinned by the forklift, his back broken, and held him as he died. They slipped money into their nephew’s pocket when he hadn’t a penny to his name but was too ashamed to admit it. They did the laundry. They swept the floor. They played in the yard like a kid.

More here.

Record for hottest day ever recorded on Earth broken twice in a row

Madeleine Cuff in New Scientist:

We have just experienced the hottest day ever recorded on Earth – for the second day in a row. The average global air temperature recorded 2 metres above Earth’s surface hit 17.18°C (62.92°F) on 4 July, according to data from the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and compiled by the University of Maine.

We have just experienced the hottest day ever recorded on Earth – for the second day in a row. The average global air temperature recorded 2 metres above Earth’s surface hit 17.18°C (62.92°F) on 4 July, according to data from the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and compiled by the University of Maine.

The new record outstrips the previous high of 17.01°C (62.62°F) set on 3 July. It makes 4 July the hottest day ever on Earth since records began.

Before that, the next highest-temperature on record was recorded jointly in August 2016 and July 2022, when average global temperatures reached 16.92°C (62.46°F).

More here.

Richard Feynman: Can Machines Think?

Why economic crashes boost globalization — and tear it apart

Mark Buchanan in Nature:

In the mid-1920s, the mood in the United States was buoyant. After years of surging economic growth, fuelled by expansion in the automobile industry and speculation in financial markets, the United States had the lowest debt of any large industrial nation. The future looked just as rosy. A 1926 article in The Wall Street Journal noted how “American wealth has doubled in the past dozen years”, delivering “a rate of progress that has never been known in Europe”.

In the mid-1920s, the mood in the United States was buoyant. After years of surging economic growth, fuelled by expansion in the automobile industry and speculation in financial markets, the United States had the lowest debt of any large industrial nation. The future looked just as rosy. A 1926 article in The Wall Street Journal noted how “American wealth has doubled in the past dozen years”, delivering “a rate of progress that has never been known in Europe”.

That astonishing uptick was real. Yet the exuberant mood vanished just a few years later with the stock-market crash of October 1929, followed by a wave of bank failures. As the trouble spread to Europe, more banks succumbed, and the world entered the Great Depression. But the seeds of this downturn were evident even during the boom. US authorities worried over how financial innovations — including the invention of derivative contracts such as options — had created a vast network of overextended investors engaging in risky speculation.

What was so new — and had for a time seemed so beneficial — led instead to profound upheaval and a global social and economic crisis.

Similar events, historian Harold James argues in his illuminating book Seven Crashes, recur across human history. Sudden outbursts of novelty presage most major economic crises.

More here.