Scott Alexander in Astral Codex Ten:

Sometimes scholars go on a search for “the historical Jesus”. They start with the Gospels, then subtract everything that seems magical or implausible, then declare whatever’s left to be the truth.

Sometimes scholars go on a search for “the historical Jesus”. They start with the Gospels, then subtract everything that seems magical or implausible, then declare whatever’s left to be the truth.

The Alexander Romance is what happens when you spend a thousand years running this process in reverse. Each generation, you make the story of Alexander the Great a little wackier. By the Middle Ages, Alexander is fighting dinosaurs and riding a chariot pulled by griffins up to Heaven.

People ate it up. The Romance stayed near the top of the best-seller lists for over a thousand years. Some people claim (without citing sources) that it was the #2 most-read book of antiquity and the Middle Ages, after only the Bible. The Koran endorses it, the Talmud embellishes it, a Mongol Khan gave it rave reviews. While historians and critics tend to use phrases like “contains nothing of historic or literary value”, this was the greatest page-turner of the ancient and medieval worlds.

More here.

The scientist behind a

The scientist behind a  Some call it “wokeness”—a word that once felt right but now feels more like an overbroad culture-war term of abuse. Others might call it social-justice extremism. But that seems too charitable: True “social justice” is about helping the world’s poor and (truly) oppressed, whereas the fashionable ideology we’re talking about here is more about privileged westerners demanding correct pronoun usage and race quotas in movie casting. As

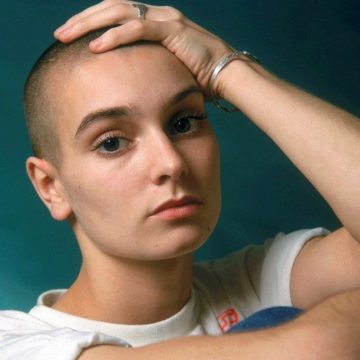

Some call it “wokeness”—a word that once felt right but now feels more like an overbroad culture-war term of abuse. Others might call it social-justice extremism. But that seems too charitable: True “social justice” is about helping the world’s poor and (truly) oppressed, whereas the fashionable ideology we’re talking about here is more about privileged westerners demanding correct pronoun usage and race quotas in movie casting. As  I always thought that the song Troy by Sinéad O’Connor was a song about romantic love. But she explained, some years ago, that the song is really about her mother. Sinéad did not like her mother, who died in a car crash when Sinéad was eighteen and who she described as extremely physically and mentally abusive. I’m going to continue to refer to Sinéad O’Connor as simply Sinéad, by the way, since I feel that intimately about her and since she will always be Sinéad to me.

I always thought that the song Troy by Sinéad O’Connor was a song about romantic love. But she explained, some years ago, that the song is really about her mother. Sinéad did not like her mother, who died in a car crash when Sinéad was eighteen and who she described as extremely physically and mentally abusive. I’m going to continue to refer to Sinéad O’Connor as simply Sinéad, by the way, since I feel that intimately about her and since she will always be Sinéad to me. Spider silk has been eyed as a greener alternative to synthetic fibres, which are derived from fossil fuels and leach harmful microplastics into the environment. Farming silk from spiders themselves is difficult, however, because they

Spider silk has been eyed as a greener alternative to synthetic fibres, which are derived from fossil fuels and leach harmful microplastics into the environment. Farming silk from spiders themselves is difficult, however, because they  AI’s capacity for agency is an urgent ethical matter because for every agent there is a patient. For every actor, there is a person or thing being acted upon. The fundamental question of politics, which deftly distinguishes ruler and ruled, is “Who, whom?,” as Trotsky paraphrased Lenin. C. S. Lewis (without quite meaning to) became an unlikely respondent to this question. In The Abolition of Man, he wrote that “what we call Man’s power over nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with nature as its instrument.” His answer works well for our context. On the individual level, technology often serves as an extension of the self. The automobile aids motion, while the cloud computer enhances memory. Yet on the social level, such technologies inevitably introduce new hierarchies and restraints. The small-town shopkeeper is run out of business by the highway bypass and the chain-store complex; reliance on Google’s products turns the user’s attention itself into a profitable product. AI opens whole new vistas for the latter kind of power-over-others, which has aptly been called “surveillance capitalism.”

AI’s capacity for agency is an urgent ethical matter because for every agent there is a patient. For every actor, there is a person or thing being acted upon. The fundamental question of politics, which deftly distinguishes ruler and ruled, is “Who, whom?,” as Trotsky paraphrased Lenin. C. S. Lewis (without quite meaning to) became an unlikely respondent to this question. In The Abolition of Man, he wrote that “what we call Man’s power over nature turns out to be a power exercised by some men over other men with nature as its instrument.” His answer works well for our context. On the individual level, technology often serves as an extension of the self. The automobile aids motion, while the cloud computer enhances memory. Yet on the social level, such technologies inevitably introduce new hierarchies and restraints. The small-town shopkeeper is run out of business by the highway bypass and the chain-store complex; reliance on Google’s products turns the user’s attention itself into a profitable product. AI opens whole new vistas for the latter kind of power-over-others, which has aptly been called “surveillance capitalism.” I

I None of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), outlined in 2015, will be met by the self-imposed 2030 deadline. Governments and leaders are better at making promises than at keeping them, scientists have told Nature. However, there are signs that the SDG agenda is having an impact, they say.

None of the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), outlined in 2015, will be met by the self-imposed 2030 deadline. Governments and leaders are better at making promises than at keeping them, scientists have told Nature. However, there are signs that the SDG agenda is having an impact, they say. Some three millennia ago, a blind bard whose name in ancient Greek means “hostage” is said to have composed two masterpieces of oral poetry that still speak to us. The Iliad’s subject is death, and the Odyssey’s is survival. Both plumb the male psyche and women’s enthrallment to its bravado. “Tell the old story for our modern times,” Homer entreats his muse, in the Odyssey’s first stanza. The translator Emily Wilson took him at his word. Her radically plainspoken

Some three millennia ago, a blind bard whose name in ancient Greek means “hostage” is said to have composed two masterpieces of oral poetry that still speak to us. The Iliad’s subject is death, and the Odyssey’s is survival. Both plumb the male psyche and women’s enthrallment to its bravado. “Tell the old story for our modern times,” Homer entreats his muse, in the Odyssey’s first stanza. The translator Emily Wilson took him at his word. Her radically plainspoken  We do not typically think in our everyday interactions with them of states and corporations as vast, powerful, long-lived, non-human ‘intelligences’. But, as Runciman rightly reminds us, the premier theorist of the modern state, Thomas Hobbes, explicitly conceived of it in such terms. A long intellectual tradition, likewise, has emphasised that states and corporations, organised alike through bureaucratic forms that restrict the personal spontaneity of their human components via techniques of abstraction and routinisation, possess peculiar modes of ‘thinking’ that are not quite comparable to the way individual people think. Theorists like Emile Durkheim, Max Weber and Michel Foucault registered, with different degrees of admiration and horror, their recognition that the modern era had witnessed the almost total subsuming of human life, at least in the developed world, into forms imposed on it by these artificial intelligences.

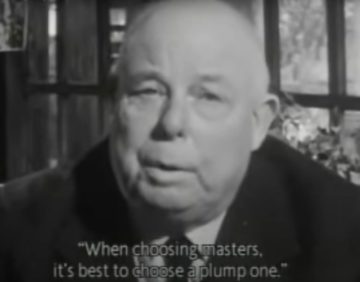

We do not typically think in our everyday interactions with them of states and corporations as vast, powerful, long-lived, non-human ‘intelligences’. But, as Runciman rightly reminds us, the premier theorist of the modern state, Thomas Hobbes, explicitly conceived of it in such terms. A long intellectual tradition, likewise, has emphasised that states and corporations, organised alike through bureaucratic forms that restrict the personal spontaneity of their human components via techniques of abstraction and routinisation, possess peculiar modes of ‘thinking’ that are not quite comparable to the way individual people think. Theorists like Emile Durkheim, Max Weber and Michel Foucault registered, with different degrees of admiration and horror, their recognition that the modern era had witnessed the almost total subsuming of human life, at least in the developed world, into forms imposed on it by these artificial intelligences. There was a period in my twenties when I found it important to adopt the attitudes and dispositions of a cinephile. I drove to Tower Records on Broadway in Downtown Sacramento, fifteen miles both ways, to rent VHS tapes of the works of F. W. Murnau, Satyajit Ray, Carl Theodor Dreyer. I considered it a great virtue to sit through hours of Stan Brakhage’s abstractions. I was, in truth, deeply bored by Yasujiro Ozu’s quiet people with their little lives, but I took the willingness to endure this boredom likewise as a mark of a special species of virtue — the cinephile virtue. (I have rewatched Ozu in more recent years and have found his work utterly compelling.) I strained to read the Cahiers du Cinéma, barely understanding a word, but loving the adoration those French intellos were willing to shower upon, say, Clint Eastwood, or, in the back catalogue of issues, the love that poured forth from François Truffaut and Jean-Pierre Melville for the most common run of American policiers. It seemed to me that cinephilia, in the particular form it took in the twentieth century, was the most thriving and generous bastion of true humanism, where it was generally understood to be something best expressed in sensibility and attention, rather than in any particular concrete message. No one, I still think, embodied this humanism more fully than Jean Renoir.

There was a period in my twenties when I found it important to adopt the attitudes and dispositions of a cinephile. I drove to Tower Records on Broadway in Downtown Sacramento, fifteen miles both ways, to rent VHS tapes of the works of F. W. Murnau, Satyajit Ray, Carl Theodor Dreyer. I considered it a great virtue to sit through hours of Stan Brakhage’s abstractions. I was, in truth, deeply bored by Yasujiro Ozu’s quiet people with their little lives, but I took the willingness to endure this boredom likewise as a mark of a special species of virtue — the cinephile virtue. (I have rewatched Ozu in more recent years and have found his work utterly compelling.) I strained to read the Cahiers du Cinéma, barely understanding a word, but loving the adoration those French intellos were willing to shower upon, say, Clint Eastwood, or, in the back catalogue of issues, the love that poured forth from François Truffaut and Jean-Pierre Melville for the most common run of American policiers. It seemed to me that cinephilia, in the particular form it took in the twentieth century, was the most thriving and generous bastion of true humanism, where it was generally understood to be something best expressed in sensibility and attention, rather than in any particular concrete message. No one, I still think, embodied this humanism more fully than Jean Renoir. Several countries, including the US, Canada and the UK, have approved new covid-19 booster vaccines, targeting a more recent variant than the boosters used last year. Here is what you need to know.

Several countries, including the US, Canada and the UK, have approved new covid-19 booster vaccines, targeting a more recent variant than the boosters used last year. Here is what you need to know. It is no longer just our leaders we must fear, but a whole section of the population. The banality of evil, the normalisation of evil is now manifest in our streets, in our classrooms, in very many public spaces. The mainstream press, the hundreds of 24-hour news channels have been harnessed to the cause of fascist majoritarianism. India’s Constitution has been effectively set aside. The Indian Penal Code is being rewritten. If the current regime wins a majority in 2024, it is very likely that we will see a new Constitution.

It is no longer just our leaders we must fear, but a whole section of the population. The banality of evil, the normalisation of evil is now manifest in our streets, in our classrooms, in very many public spaces. The mainstream press, the hundreds of 24-hour news channels have been harnessed to the cause of fascist majoritarianism. India’s Constitution has been effectively set aside. The Indian Penal Code is being rewritten. If the current regime wins a majority in 2024, it is very likely that we will see a new Constitution.