Ken Roth in The Guardian:

Watching lawyers for South Africa and Israel debate whether Israel is committing genocide in Gaza was like observing two versions of reality that barely intersect.

Watching lawyers for South Africa and Israel debate whether Israel is committing genocide in Gaza was like observing two versions of reality that barely intersect.

Each set of counsel, appearing before the international court of justice at The Hague, largely avoided the most powerful evidence contradicting their case, and the absence of a factual hearing or any questioning left it unclear how the judges will resolve the dispute. Yet I would wager that South Africa’s case was strong enough that the court will impose some provisional measures on Israel in the hope of mitigating the enormous civilian harm caused by Israel’s approach to fighting Hamas.

More here.

On March 31, 1968, days before he would be assassinated, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

On March 31, 1968, days before he would be assassinated, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.  The Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue’s new novel has a soft, nebulous title: “You Dreamed of Empires.” Its cover is forgettable, too. Like nearly every book on the New Fiction table, it is all wavy patterns and beach-towel colors. This generic look has come to promise a) bright settings and b) young characters out to conquer racial and sexual threats as they perceive them. This would be excellent were it not for, as often as not, c) writing in which one is instructed how to feel at almost every moment.

The Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue’s new novel has a soft, nebulous title: “You Dreamed of Empires.” Its cover is forgettable, too. Like nearly every book on the New Fiction table, it is all wavy patterns and beach-towel colors. This generic look has come to promise a) bright settings and b) young characters out to conquer racial and sexual threats as they perceive them. This would be excellent were it not for, as often as not, c) writing in which one is instructed how to feel at almost every moment. A

A The Aug. 13, 2021 edition of The New York Times failed to mention the 500th anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlan, the erstwhile Aztec capital out of which Mexico City was born. Álvaro Enrigue noticed. Of course.

The Aug. 13, 2021 edition of The New York Times failed to mention the 500th anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlan, the erstwhile Aztec capital out of which Mexico City was born. Álvaro Enrigue noticed. Of course. Ryan Crownholm, a middle-aged Army veteran with luminous green eyes and a strong jawline, likes to describe himself as a health hacker. He has written on LinkedIn that, after founding and running several construction-related companies, he started to think of his own body as a data source. During the pandemic, he attached a continuous glucose monitor to his skin, bought an

Ryan Crownholm, a middle-aged Army veteran with luminous green eyes and a strong jawline, likes to describe himself as a health hacker. He has written on LinkedIn that, after founding and running several construction-related companies, he started to think of his own body as a data source. During the pandemic, he attached a continuous glucose monitor to his skin, bought an  O

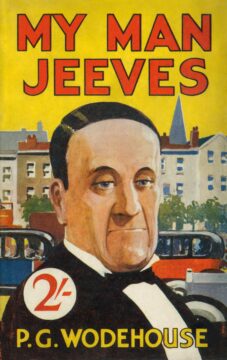

O Douglas Adams called him “the greatest comic writer ever.” Hilaire Belloc went so far as to pronounce him “the best living writer of English,” and rather than retract that excessive praise he explained it. P.G. Wodehouse had perfectly accomplished what he set out to do: create and sustain a world that would amuse us.

Douglas Adams called him “the greatest comic writer ever.” Hilaire Belloc went so far as to pronounce him “the best living writer of English,” and rather than retract that excessive praise he explained it. P.G. Wodehouse had perfectly accomplished what he set out to do: create and sustain a world that would amuse us.