Category: Recommended Reading

The Art Of Sam Gilliam

Julia Bryan-Wilson at Artforum:

SAM GILLIAM’S 1980 painting Robbin’ Peter seethes with pigment. The colors densely clot in some areas and in others are scraped flat to reveal the weave of the raw fabric canvas. Reds and blues clump and splat and drip, interrupted by short linear marks dragged through the paint to create rhythmic grooves. The work is a puzzle-like collage of previous Gilliam paintings, which have been cut up, reassembled, and glued in patchwork-quilt fashion, and in fact it takes its name from a vernacular quilt pattern known as “Robbing Peter to Pay Paul”—conventionally, a two-color needlework with curved diamond seams and overlapping, interlocked quartered circles. The pattern is found on quilts across the United States from the nineteenth century to the present day and is sometimes called simply, as Gilliam’s title acknowledges, “Robbing Peter.”1 Part of “Chasers,” a series of nine-sided works that Gilliam made between circa 1980 and 1982, pursuing in the process his always restless experiments with texture, shape, and surface, the quilt painting is muscular and assertive, pressing into space with its thick, built-up impasto excrescences.

SAM GILLIAM’S 1980 painting Robbin’ Peter seethes with pigment. The colors densely clot in some areas and in others are scraped flat to reveal the weave of the raw fabric canvas. Reds and blues clump and splat and drip, interrupted by short linear marks dragged through the paint to create rhythmic grooves. The work is a puzzle-like collage of previous Gilliam paintings, which have been cut up, reassembled, and glued in patchwork-quilt fashion, and in fact it takes its name from a vernacular quilt pattern known as “Robbing Peter to Pay Paul”—conventionally, a two-color needlework with curved diamond seams and overlapping, interlocked quartered circles. The pattern is found on quilts across the United States from the nineteenth century to the present day and is sometimes called simply, as Gilliam’s title acknowledges, “Robbing Peter.”1 Part of “Chasers,” a series of nine-sided works that Gilliam made between circa 1980 and 1982, pursuing in the process his always restless experiments with texture, shape, and surface, the quilt painting is muscular and assertive, pressing into space with its thick, built-up impasto excrescences.

more here.

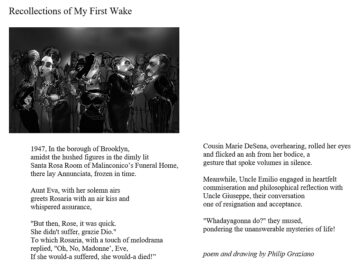

Friday Poem

Question

Body my house

my horse my hound

what will I do

when you are fallen

Where will I sleep

How will I ride

What will I hunt

Where can I go

without my mount

all eager and quick

How will I know

in thicket ahead

is danger or treasure

when Body my good

bright dog is dead

How will it be

to lie in the sky

without roof or door

and wind for an eye

With cloud for shift

how will I hide?

by May Swenson

from Strong Measures

Harper Collins, 1986

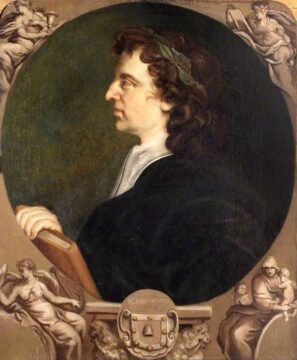

Why Read John Milton?

Ed Simon in The Millions:

As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene on multiple choice tests. In the spring semester of 2004, I was more concerned with Yuengling than I was with Geoffrey Chaucer or the Pearl Poet, so I fully deserved the middling grade that I got.

As a sophomore in college, I completely earned the C+ that I received in a survey course called “British Literature.” There could be no blaming of the professor on my end, no skirting responsibility for those missed assignments, no excuse for having confused Belphoebe for Gloriana in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene on multiple choice tests. In the spring semester of 2004, I was more concerned with Yuengling than I was with Geoffrey Chaucer or the Pearl Poet, so I fully deserved the middling grade that I got.

Yet that class was also the site of an important discovery: the stern, austere, blind Puritan bard John Milton. For the past two decades, I’ve read and reread Milton, written about Milton, taught Milton, thought about Milton. I don’t know if I’m any closer to really understanding his greatest work, for that magisterial 1667 poem Paradise Lost is a cosmos unto itself, like Dante’s The Divine Comedy or Melville’s Moby-Dick, but I know that my life wouldn’t be as rich without it.

“Of Man’s first disobedience, and the fruit / Of that forbidden tree whose mortal taste / Brought death into the world, and all our woe,” intones the poet in Paradise Lost, still resonating across nearly three-and-a-half centuries, a writer who even when he is dry or slow (and he can be dry and slow) still can turn a phrase and deploy it to stunningly dramatic effect in this epic tale about Satan’s rebellion against God in Heaven and the subsequent fall of humanity and all Creation.

More here.

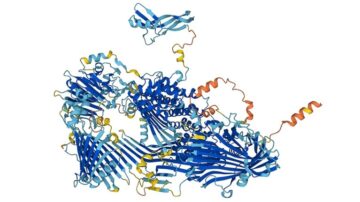

AlphaFold found thousands of possible psychedelics. Will its predictions help drug discovery?

Ewen Callaway in Nature:

Researchers have used the protein-structure-prediction tool AlphaFold to identify1 hundreds of thousands of potential new psychedelic molecules — which could help to develop new kinds of antidepressant. The research shows, for the first time, that AlphaFold predictions — available at the touch of a button — can be just as useful for drug discovery as experimentally derived protein structures, which can take months, or even years, to determine.

Researchers have used the protein-structure-prediction tool AlphaFold to identify1 hundreds of thousands of potential new psychedelic molecules — which could help to develop new kinds of antidepressant. The research shows, for the first time, that AlphaFold predictions — available at the touch of a button — can be just as useful for drug discovery as experimentally derived protein structures, which can take months, or even years, to determine.

The development is a boost for AlphaFold, the artificial-intelligence (AI) tool developed by DeepMind in London that has been a game-changer in biology. The public AlphaFold database holds structure predictions for nearly every known protein. Protein structures of molecules implicated in disease are used in the pharmaceutical industry to identify and improve promising medicines. But some scientists had been starting to doubt whether AlphaFold’s predictions could stand-in for gold standard experimental models in the hunt for new drugs.

“AlphaFold is an absolute revolution. If we have a good structure, we should be able to use it for drug design,” says Jens Carlsson, a computational chemist at the University of Uppsala in Sweden.

More here.

Thursday, January 18, 2024

Some truly unhinged entertaining advice

Amy McCarthy at Eater:

Your napkins need to be folded in a way that suggests you hold a degree in structural engineering.

Your napkins need to be folded in a way that suggests you hold a degree in structural engineering.

Published in 1888, How to Fold Napkins by Jessup Whitehead remains a comprehensive guide to the most maniacal folded napkin designs. “The eye must be feasted as well as the palate,” Whitehead wrote. Within the book’s pages, you can learn how to fold crisp linen into a fleur-de-lys, a crown, a bridal serviette, or a Double Horn of Plenty (whatever that is). Notably, you will need a lot of starch to make most of these feats of napkin architecture happen.

More here.

Review of “How Life Works” by Philip Ball

Adam Rutherford in The Guardian:

You might think, with the completion of the Human Genome Project 20 years ago now, and the discovery of the double helix enjoying its 70th birthday this year, that we actually know how life works. In physics, the quest for a so-called Grand Unifying Theory has preoccupied the most ambitious minds for generations, alas to no avail. But in the life sciences, we managed to find four grand unifying theories in the space of 100 years or so. Three are well known: cell theory – all life is made of cells, which only come from existing cells; Darwin’s evolution by natural selection; and universal genetics – all life is encoded by a cypher written in the molecule DNA. The fourth, no less important, goes by the chewy name chemiosmosis, and describes the way that all living things live by drawing fuel from their surroundings and using it in a continuous chemical reaction. In summary, life, made of cells that extract energy from their environment, comes modified from what came before. Job done; suck it, physicists!

You might think, with the completion of the Human Genome Project 20 years ago now, and the discovery of the double helix enjoying its 70th birthday this year, that we actually know how life works. In physics, the quest for a so-called Grand Unifying Theory has preoccupied the most ambitious minds for generations, alas to no avail. But in the life sciences, we managed to find four grand unifying theories in the space of 100 years or so. Three are well known: cell theory – all life is made of cells, which only come from existing cells; Darwin’s evolution by natural selection; and universal genetics – all life is encoded by a cypher written in the molecule DNA. The fourth, no less important, goes by the chewy name chemiosmosis, and describes the way that all living things live by drawing fuel from their surroundings and using it in a continuous chemical reaction. In summary, life, made of cells that extract energy from their environment, comes modified from what came before. Job done; suck it, physicists!

However, biology is messy, and though we have these laws in place to describe all life on Earth, people like me remain gainfully employed because our understanding of how chemistry becomes biology is far, far from complete. These grand unifying ideas are unbeatable, but they lack detail, and in biology the devil lies at a molecular level of complexity that is hard to understand.

More here.

Behind the Scenes of Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon”

Carole Hooven: Why I Left Harvard

Carole Hooven in The Free Press:

Since early December, the end of my 20-year career teaching at Harvard has been the subject of articles, op-eds, tweets from a billionaire, and even a congressional hearing. I have become a poster child for how the growing campus DEI—Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—bureaucracies strangle free speech. My ordeal has been used to illustrate the hypocrisy of the assertions by Harvard’s leaders that they honor the robust exchange of challenging ideas.

Since early December, the end of my 20-year career teaching at Harvard has been the subject of articles, op-eds, tweets from a billionaire, and even a congressional hearing. I have become a poster child for how the growing campus DEI—Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—bureaucracies strangle free speech. My ordeal has been used to illustrate the hypocrisy of the assertions by Harvard’s leaders that they honor the robust exchange of challenging ideas.

What happened to me, and others, strongly suggests that these assertions aren’t true—at least, if those ideas oppose campus orthodoxy.

To be a central example of what has gone wrong in higher education feels surreal. If there is any silver lining to losing the career that I found so fulfilling, perhaps it’s that my story will help explain the fear that stalks campuses, a fear that spreads every time someone is punished for their speech.

More here.

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville

Three Lessons in Beauty

Trevor Cribben Merrill at Genealogies of Modernity:

In his essay Testaments Betrayed Milan Kundera recalls taking lessons in musical composition from a friend of his father’s, a Jewish composer who was at that time required to wear the yellow star. Seeing the young Kundera out of the tiny Prague flat where he camped out with others whose apartments had been confiscated, the composer suddenly stopped: “There are many surprisingly weak passages in Beethoven. But it is the weak passages that bring out the strong ones. It’s like a lawn—if it weren’t there, we couldn’t enjoy the beautiful tree growing on it.” Some time after sharing this insight with his pupil, the composer was transported to Theresienstadt. Kundera was never to forget the moment: “. . . that brief remark from my teacher of the time has haunted me all my life (I’ve defended it, I’ve fought it, I’ve never finished with it) . . .”

In his essay Testaments Betrayed Milan Kundera recalls taking lessons in musical composition from a friend of his father’s, a Jewish composer who was at that time required to wear the yellow star. Seeing the young Kundera out of the tiny Prague flat where he camped out with others whose apartments had been confiscated, the composer suddenly stopped: “There are many surprisingly weak passages in Beethoven. But it is the weak passages that bring out the strong ones. It’s like a lawn—if it weren’t there, we couldn’t enjoy the beautiful tree growing on it.” Some time after sharing this insight with his pupil, the composer was transported to Theresienstadt. Kundera was never to forget the moment: “. . . that brief remark from my teacher of the time has haunted me all my life (I’ve defended it, I’ve fought it, I’ve never finished with it) . . .”

Few of us will receive lessons in beauty under such circumstances. Yet anyone who has sought to make or comprehend art has probably come across at least a few similarly unforgettable statements—insights that, it seems, can never be exhausted. Some we accept unconditionally because they articulate an intuition we have had ourselves but were unable to express. Others we wrestle with for a long time, unwilling to give them our full assent yet equally unable to leave them behind.

more here (via The Book Haven).

Psychedelics Rapidly Fight Depression—a New Study Offers a First Hint at Why

Shelly Fan in Singularity Hub:

Depression is like waking up to a rainy, dreary morning, every single day. Activities that previously lightened the mood lose their joy. Instead, every social interaction and memory is filtered through a negative lens. This aspect of depression, called negative affective bias, leads to sadness and rumination—where haunting thoughts tumble around endlessly in the brain. Scientists have long sought to help people out of these ruts and back into a positive mindset by rewiring neural connections. Traditional antidepressants, such as Prozac, cause these changes, but they take weeks or even months. In contrast, psychedelics rapidly trigger antidepressant effects with just one shot and last for months when administered in a controlled environment and combined with therapy.

Depression is like waking up to a rainy, dreary morning, every single day. Activities that previously lightened the mood lose their joy. Instead, every social interaction and memory is filtered through a negative lens. This aspect of depression, called negative affective bias, leads to sadness and rumination—where haunting thoughts tumble around endlessly in the brain. Scientists have long sought to help people out of these ruts and back into a positive mindset by rewiring neural connections. Traditional antidepressants, such as Prozac, cause these changes, but they take weeks or even months. In contrast, psychedelics rapidly trigger antidepressant effects with just one shot and last for months when administered in a controlled environment and combined with therapy.

Why? A new study suggests these drugs reduce negative affective bias by shaking up the brain networks that regulate emotion. In rats with low mood, a dose of several psychedelics boosted their “outlook on life.” Based on several behavioral tests, ketamine—a party drug known for its dissociative high—and the hallucinogen scopolamine shifted the rodents’ emotional state to neutral.

Psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, further turned the emotional dial towards positivity. Rather than Debbie Downers, these rats adopted a sunny mindset with an openness to further learning, replacing negative thoughts with positive ones.

More here.

Cute Little Tardigrades Are Basically Indestructible, and Scientists Just Figured Out One Reason Why

Meghan Bartels in Scientific American:

Tiny tardigrades have three claims to fame: their charmingly pudgy appearance, delightful common names (water bear and moss piglet) and stunning resilience in the face of threats ranging from the vacuum of space to temperatures near absolute zero. Now scientists have identified a key mechanism contributing to tardigrades’ resilience—a molecular switch of sorts that triggers a hardy dormant state of being. The researchers hope that the new work, published on January 17 in the journal PLOS ONE, will encourage further exploration of the microscopic creatures’ ability to withstand extreme conditions.

Tiny tardigrades have three claims to fame: their charmingly pudgy appearance, delightful common names (water bear and moss piglet) and stunning resilience in the face of threats ranging from the vacuum of space to temperatures near absolute zero. Now scientists have identified a key mechanism contributing to tardigrades’ resilience—a molecular switch of sorts that triggers a hardy dormant state of being. The researchers hope that the new work, published on January 17 in the journal PLOS ONE, will encourage further exploration of the microscopic creatures’ ability to withstand extreme conditions.

The research began back when, on a whim, co-author Derrick Kolling, a chemist at Marshall University, put a tardigrade into a machine that detects “free radicals,” or atoms that contain unpaired electrons. And he did see such atoms being produced in the water bear. That finding isn’t surprising because an animal’s normal metabolic processes, as well as environmental stressors such as smoke and other pollutants, create free radicals inside cells.

When they build up, free radicals—most notably reactive forms of oxygen—snatch electrons from their surroundings to achieve stability in a process known as oxidation. In the process, these radicals damage cells and compounds such as DNA and proteins. But in small quantities, free radicals can act as signaling molecules, Hicks says, and her lab studies show how these atoms affect a cell’s behavior by glomming on to and popping off a variety of proteins. When Kolling told Hicks about seeing free radicals in a tardigrade, Hicks wondered if these atoms might play a role in the animal’s hardiness. The team devised several experiments to temporarily expose little water bears to stress-inducing, free-radical-producing conditions—including high levels of salt, sugar and hydrogen peroxide. Under these forms of stress, tardigrades curl up into a temporary protective state of dormancy called a tun. “When there’s a lot of stress, they’re masters of protecting themselves,” Kolling says.

More here.

Dickson Despommier Wants Our Cities to Be Like Forests

Jon Michaud at The New Yorker:

In 2000, Dickson D. Despommier, then a professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia University, was teaching a class on medical ecology in which he asked his students, “What will the world be like in 2050?,” and a follow-up, “What would you like the world to be like in 2050?” As Despommier told The New Yorker’s Ian Frazier in 2017, his students “decided that by 2050 the planet will be really crowded, with eight or nine billion people, and they wanted New York City to be able to feed its population entirely on crops grown within its own geographic limit.” The class had calculated that by farming every square foot of rooftop space in the city, you could provide enough calories to feed only about two per cent of the 2050 population of New York.

In 2000, Dickson D. Despommier, then a professor of public health and microbiology at Columbia University, was teaching a class on medical ecology in which he asked his students, “What will the world be like in 2050?,” and a follow-up, “What would you like the world to be like in 2050?” As Despommier told The New Yorker’s Ian Frazier in 2017, his students “decided that by 2050 the planet will be really crowded, with eight or nine billion people, and they wanted New York City to be able to feed its population entirely on crops grown within its own geographic limit.” The class had calculated that by farming every square foot of rooftop space in the city, you could provide enough calories to feed only about two per cent of the 2050 population of New York.

Urban farming was a good idea, Despommier thought, but his students hadn’t taken it far enough. “What’s wrong with putting the farmer inside the building?” he asked them, remembering that at the time there were “hundreds to perhaps thousands” of empty buildings in New York City. Throughout the next decade, as he continued to teach the class, Despommier and his students developed this idea—including the use of cultivation techniques that required little or no soil—culminating in the 2010 book, “The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century.”

more here.

Thursday Poem

I thought I was following a track of freedom

and for awhile it was —Adrienne Rich

Rivers/Roads

Consider the earnestness of pavement

its dark elegant sheen after rain,

its insistence on leading you somewhere

A highway wants to own the landscape,

it sections prairie into neat squares

swallows mile after mile of countryside

to connect the dots of cities and towns,

to make sense of things

A river is less opinionated

less predictable

it never argues with gravity

its history is a series of delicate negotiations with

time and geography

Wet your feet all you want

Heraclitus says,

it’s never the river you remember;

a road repeats itself incessantly

obsessed with its own small truth,

it wants you to believe in something particular

The destination you have in mind when you set out

is nowhere you have ever been;

where you arrive finally depends on

how you get there,

by river or by road

by Michael Crummey

from Arguments With Gravity.

Quarry Press, Kingston, Ont. 1996.

Wednesday, January 17, 2024

Invisible Ink: At the CIA’s Creative Writing Group

Johannes Lichtman in The Paris Review:

As I considered the invitation, I kept wondering why I’d been invited. I don’t write about CIA-adjacent topics, nor am I successful enough a novelist that people outside a small circle—one that I doubt includes U.S. intelligence agencies—know my name. So the invite was a bit of a mystery. This was the second-most common question that came up when I told writer friends about it, topped only by: “No speaking fee?” At first, I wondered whether the gig was part of a recruitment strategy. But it doesn’t take a vast intelligence apparatus to know that I am not intelligence material, not least because I am a professional writer.

As I considered the invitation, I kept wondering why I’d been invited. I don’t write about CIA-adjacent topics, nor am I successful enough a novelist that people outside a small circle—one that I doubt includes U.S. intelligence agencies—know my name. So the invite was a bit of a mystery. This was the second-most common question that came up when I told writer friends about it, topped only by: “No speaking fee?” At first, I wondered whether the gig was part of a recruitment strategy. But it doesn’t take a vast intelligence apparatus to know that I am not intelligence material, not least because I am a professional writer.

Next I wondered if my visit could be used as soft-diplomacy propaganda. Look how harmless we are! We let writers come to our headquarters and pose for pictures. The CIA had veered into this type of literary boosterism before—supporting, for example, the founding of the very magazine for which I am writing this piece. So it wasn’t out of the question.

More here.

Should nations try to ban bitcoin because of its environmental impact?

Matthew Sparkes in New Scientist:

The amount of electricity used to mine and trade bitcoin climbed to 121 terawatt-hours in 2023, 27 per cent more than the previous year. While other cryptocurrencies in the same position have made bold changes to cut their impact, bitcoin’s decentralised community of developers, miners and investors are showing little interest in changing course. If bitcoin cannot clean up its own house, should governments step in to shut it down?

The amount of electricity used to mine and trade bitcoin climbed to 121 terawatt-hours in 2023, 27 per cent more than the previous year. While other cryptocurrencies in the same position have made bold changes to cut their impact, bitcoin’s decentralised community of developers, miners and investors are showing little interest in changing course. If bitcoin cannot clean up its own house, should governments step in to shut it down?

The latest data from the University of Cambridge shows that bitcoin currently accounts for 0.69 per cent of all electricity consumption worldwide. It also requires vast amounts of water, both for electricity production and for cooling at data centres. A study last year found that a single bitcoin transaction uses enough water to fill a swimming pool.

More here.

Where Now for Nuclear Power?

James B. Meigs in City Journal:

As 2024 dawns, the prospects for a nuclear revival in the U.S. look mixed. On one hand, many once-skeptical environmentalists now support the technology. Bipartisan majorities in Congress back funding for nuclear research and deployment. And more than two dozen startups are developing a new generation of small, innovative reactor designs. But momentum slowed in November, when NuScale Power, the Portland, Oregon-based company pioneering small modular reactors (SMRs), announced the cancellation of its showcase project to build a power facility in Idaho. If completed, the project would have been the nation’s first SMR power plant. Backers hoped that the endeavor would prove that this new approach to nuclear technology can deliver affordable, zero-carbon power to our electric grid. Instead, delays and escalating costs forced NuScale to shelve the project before it even broke ground.

As 2024 dawns, the prospects for a nuclear revival in the U.S. look mixed. On one hand, many once-skeptical environmentalists now support the technology. Bipartisan majorities in Congress back funding for nuclear research and deployment. And more than two dozen startups are developing a new generation of small, innovative reactor designs. But momentum slowed in November, when NuScale Power, the Portland, Oregon-based company pioneering small modular reactors (SMRs), announced the cancellation of its showcase project to build a power facility in Idaho. If completed, the project would have been the nation’s first SMR power plant. Backers hoped that the endeavor would prove that this new approach to nuclear technology can deliver affordable, zero-carbon power to our electric grid. Instead, delays and escalating costs forced NuScale to shelve the project before it even broke ground.

More here.

Yuval Noah Harari on AI, Free Will, War, and other topics

Wednesday Poem