Sarah Burch in Jacobin:

On Sunday, while one hundred million Americans were watching the kickoff of the Super Bowl, Israel took the opportunity to unleash the next stage in its genocide of Palestinians. Air strikes over Rafah killed at least sixty-seven Palestinians, while Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu ordered soldiers to prepare for a ground entry into the city.

Rafah, on Gaza’s southern border with Egypt, is the last refuge for nearly 1.5 million Palestinians displaced by the ongoing Israeli genocide.

Since Israeli bombs began decimating Northern Gaza in October, Palestinians have been told to evacuate to the south. Rafah is as far south as anyone can go. With a ground invasion imminent, the Israeli government is calling for the population to “evacuate” — even though they have nowhere to evacuate to.

An Israeli invasion of Rafah would be the most dangerous stage of the genocide yet, causing death on a scale unseen even in these four months of sheer brutality.

After indiscriminately flattening Gaza and pushing Palestinians toward famine, now the Israeli military is seeking to remove the Palestinians from Gaza permanently, whether by displacement, disease, hunger, or execution.

More here.

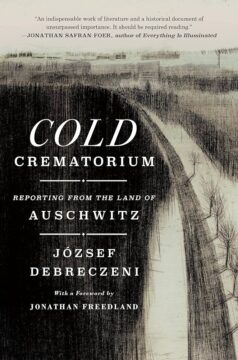

József Debreczeni’s memoir of the Nazi death camps, translated into English from Hungarian for the first time, frequently echoes Edgar’s claim. After being moved from “the capital of the Great Land of Auschwitz” to one of the networks of sub-camps, Eule, he discovers that he is to be moved again: “Surely I couldn’t end up in a place much worse, I thought – and how tragically wrong I was.” By the end of his remarkable set of observational writings, the word “worse” has lost all meaning; comparing the depths of human experiences of depravity and suffering feels obscene in itself. Is typhoid worse than starvation? Is being crushed to death while mining a subterranean tunnel worse than wasting away in a pool of one’s own filth?

József Debreczeni’s memoir of the Nazi death camps, translated into English from Hungarian for the first time, frequently echoes Edgar’s claim. After being moved from “the capital of the Great Land of Auschwitz” to one of the networks of sub-camps, Eule, he discovers that he is to be moved again: “Surely I couldn’t end up in a place much worse, I thought – and how tragically wrong I was.” By the end of his remarkable set of observational writings, the word “worse” has lost all meaning; comparing the depths of human experiences of depravity and suffering feels obscene in itself. Is typhoid worse than starvation? Is being crushed to death while mining a subterranean tunnel worse than wasting away in a pool of one’s own filth? What a document dump!

What a document dump! We find similar ideas of a transcendent ego in both Kant and the Upanishads. We find a rejection of free will in Schopenhauer and Ramana Maharshi. What should we make of this overlap between Western and Indian philosophy? Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad argues both became gripped by the same question.

We find similar ideas of a transcendent ego in both Kant and the Upanishads. We find a rejection of free will in Schopenhauer and Ramana Maharshi. What should we make of this overlap between Western and Indian philosophy? Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad argues both became gripped by the same question. Brooklyn-based artist

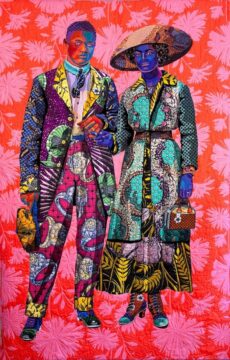

Brooklyn-based artist  Elizabeth Amelia Gloucester appeared in the census for the final time on June 8, 1880. The census enumerators who crisscrossed Brooklyn Heights were no doubt surprised to find a wealthy Black woman presiding over Remsen House, the grand boarding hotel not far from Brooklyn City Hall that served the white professional classes. Ms. Gloucester was a pillar of the

Elizabeth Amelia Gloucester appeared in the census for the final time on June 8, 1880. The census enumerators who crisscrossed Brooklyn Heights were no doubt surprised to find a wealthy Black woman presiding over Remsen House, the grand boarding hotel not far from Brooklyn City Hall that served the white professional classes. Ms. Gloucester was a pillar of the  Since its inception with the

Since its inception with the  Instruments deployed in the ocean starting in 2004

Instruments deployed in the ocean starting in 2004  THE CANARY ISLANDS—

THE CANARY ISLANDS— In an anonymously published essay, “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” George Eliot set out her objections to “mind-and-millinery” novels: those books featuring dazzling heroines—eloquent, accomplished, almost godly—who set off into the world solely in pursuit of an amiable husband. Castigating the genre for its “drivelling” narratives, clichéd characters, and hackneyed morals, Eliot argued that novels that posit marriage as a woman’s ultimate aim and achievement only “confirm the popular prejudice against the more solid education of women.” In her own writing, Eliot set out not just to rehash the “marriage plot” but to expose and dissect it: Her sweeping novels show her utterly human characters grappling with the harsh disparities between societal expectations of married life and their own, often painful experiences of it.

In an anonymously published essay, “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” George Eliot set out her objections to “mind-and-millinery” novels: those books featuring dazzling heroines—eloquent, accomplished, almost godly—who set off into the world solely in pursuit of an amiable husband. Castigating the genre for its “drivelling” narratives, clichéd characters, and hackneyed morals, Eliot argued that novels that posit marriage as a woman’s ultimate aim and achievement only “confirm the popular prejudice against the more solid education of women.” In her own writing, Eliot set out not just to rehash the “marriage plot” but to expose and dissect it: Her sweeping novels show her utterly human characters grappling with the harsh disparities between societal expectations of married life and their own, often painful experiences of it. ALMOST IMMEDIATELY after melodrama had its heyday in the mid-19th century, it began to be mocked for being obsolete. In an 1890 burlesque of Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca, the play later adapted into a more famous opera, the police chief Scarpia proudly admits that, as a villain intent on “possess[ing]” the play’s titular heroine, he is a vestige of “that dark age / when curdling melodrama held the stage.” Belonging to a genre that has come to feel more campy than poignant, even villains like Scarpia can’t take themselves seriously. And yet, no matter how many generations have claimed to have evolved away from a genre besmirched for its expressive storytelling and moral polarities, melodrama has retained its power as a way for artists to represent the world and as a lens for critics to interpret what they see.

ALMOST IMMEDIATELY after melodrama had its heyday in the mid-19th century, it began to be mocked for being obsolete. In an 1890 burlesque of Victorien Sardou’s La Tosca, the play later adapted into a more famous opera, the police chief Scarpia proudly admits that, as a villain intent on “possess[ing]” the play’s titular heroine, he is a vestige of “that dark age / when curdling melodrama held the stage.” Belonging to a genre that has come to feel more campy than poignant, even villains like Scarpia can’t take themselves seriously. And yet, no matter how many generations have claimed to have evolved away from a genre besmirched for its expressive storytelling and moral polarities, melodrama has retained its power as a way for artists to represent the world and as a lens for critics to interpret what they see. In antiquity humans were referred to as “mortals,” which meant that they were destined not only to die but also to suffer loss, misfortune, and disaster. By comparison with the immortal gods, even the loftiest mortals are losers in the long run (as Achilles realizes in Hades). In his book In Praise of Failure, the philosopher and essayist Costica Bradatan reminds us that we flash into existence between “two instantiations of nothingness,” namely the nothingness before we were born and the one after we die. Each one of us, ontologically speaking, is next to nothing. And each one of us, despite our precarious condition, has something to lose. “Myths, religion, spirituality, philosophy, science, works of art and literature”—all, according to Bradatan, seek to make our next-to-nothingness “a little more bearable.”

In antiquity humans were referred to as “mortals,” which meant that they were destined not only to die but also to suffer loss, misfortune, and disaster. By comparison with the immortal gods, even the loftiest mortals are losers in the long run (as Achilles realizes in Hades). In his book In Praise of Failure, the philosopher and essayist Costica Bradatan reminds us that we flash into existence between “two instantiations of nothingness,” namely the nothingness before we were born and the one after we die. Each one of us, ontologically speaking, is next to nothing. And each one of us, despite our precarious condition, has something to lose. “Myths, religion, spirituality, philosophy, science, works of art and literature”—all, according to Bradatan, seek to make our next-to-nothingness “a little more bearable.”