Sophie Haigney at The Paris Review:

I like the ashes on Ash Wednesday. I am at best a lapsed Catholic though it would be more accurate to say that I never really began, just that I was raised against the backdrop of already-faded-Catholicism and its associated traumas, now transmuted and passed on in their mysterious ways to me. I inherited also the pining and the predilection that many Americans have for certain things to do with Ireland. In San Francisco, I used to drink afternoons after I got off work at an Irish bar in Noe Valley, the Valley Tavern, or a different Irish bar downtown, the Chieftain, or sometimes come to think of it an Irish bar on Guerrero with big windows where my friend Graham and I used to like to watch the rain. San Francisco is a more Catholic city than most people think, and more Irish too. More Irish American, which is really what I am talking about: girls in red school uniforms and tennis shoes outside the Convent of the Sacred Heart, looking forward to football games Friday nights at St. Ignatius, the high school by the church where my feet were washed as a kid on Holy Thursday.

I like the ashes on Ash Wednesday. I am at best a lapsed Catholic though it would be more accurate to say that I never really began, just that I was raised against the backdrop of already-faded-Catholicism and its associated traumas, now transmuted and passed on in their mysterious ways to me. I inherited also the pining and the predilection that many Americans have for certain things to do with Ireland. In San Francisco, I used to drink afternoons after I got off work at an Irish bar in Noe Valley, the Valley Tavern, or a different Irish bar downtown, the Chieftain, or sometimes come to think of it an Irish bar on Guerrero with big windows where my friend Graham and I used to like to watch the rain. San Francisco is a more Catholic city than most people think, and more Irish too. More Irish American, which is really what I am talking about: girls in red school uniforms and tennis shoes outside the Convent of the Sacred Heart, looking forward to football games Friday nights at St. Ignatius, the high school by the church where my feet were washed as a kid on Holy Thursday.

more here.

According to his memoirs, Eugène-François Vidocq escaped from more than twenty prisons (sometimes dressed as a nun). Working on the other side of the law, he apprehended some 4000 criminals with a team of plainclothes agents. He founded the first criminal investigation bureau — staffed mainly with convicts — and, when he was later fired, the first private detective agency. He was one the fathers of modern criminology and had a rap sheet longer than his very tall tales. Who was Vidocq?

According to his memoirs, Eugène-François Vidocq escaped from more than twenty prisons (sometimes dressed as a nun). Working on the other side of the law, he apprehended some 4000 criminals with a team of plainclothes agents. He founded the first criminal investigation bureau — staffed mainly with convicts — and, when he was later fired, the first private detective agency. He was one the fathers of modern criminology and had a rap sheet longer than his very tall tales. Who was Vidocq? Moving a prosthetic arm. Controlling a speaking avatar. Typing at speed. These are all things that people with paralysis have learnt to do

Moving a prosthetic arm. Controlling a speaking avatar. Typing at speed. These are all things that people with paralysis have learnt to do  Notoriously, in the winter of 1969 the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its first exhibition devoted to African American culture, but with a show devoid of art. Called “Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900—1968,” it was a photomural-with-texts affair of a kind found in ethnology museums.

Notoriously, in the winter of 1969 the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its first exhibition devoted to African American culture, but with a show devoid of art. Called “Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900—1968,” it was a photomural-with-texts affair of a kind found in ethnology museums. eDNA serves as a surveillance tool, offering researchers a means of detecting the seemingly undetectable. By sampling eDNA, or mixtures of genetic material — that is, fragments of DNA, the blueprint of life — in water, soil, ice cores, cotton swabs, or practically any environment imaginable, even thin air, it is now possible to search for a specific organism or assemble a snapshot of all the organisms in a given place. Instead of setting up a camera to see who crosses the beach at night, eDNA pulls that information out of footprints in the sand. “We’re all flaky, right?” said Robert Hanner, a biologist at the University of Guelph in Canada. “There’s bits of cellular debris sloughing off all the time.”

eDNA serves as a surveillance tool, offering researchers a means of detecting the seemingly undetectable. By sampling eDNA, or mixtures of genetic material — that is, fragments of DNA, the blueprint of life — in water, soil, ice cores, cotton swabs, or practically any environment imaginable, even thin air, it is now possible to search for a specific organism or assemble a snapshot of all the organisms in a given place. Instead of setting up a camera to see who crosses the beach at night, eDNA pulls that information out of footprints in the sand. “We’re all flaky, right?” said Robert Hanner, a biologist at the University of Guelph in Canada. “There’s bits of cellular debris sloughing off all the time.” The solution seems so obvious. A region synonymous with abundant sun is hungry for more electricity. Given Africa’s colossal untapped solar radiation, the continent should be installing solar panels at a furious pace. But it’s not. Though home to 60% of the world’s best solar resources, Africa today represents just 1% of installed solar photovoltaic capacity.

The solution seems so obvious. A region synonymous with abundant sun is hungry for more electricity. Given Africa’s colossal untapped solar radiation, the continent should be installing solar panels at a furious pace. But it’s not. Though home to 60% of the world’s best solar resources, Africa today represents just 1% of installed solar photovoltaic capacity. Art is useless, said Wilde. Art is for art’s sake—that is, for beauty’s sake. But why do we possess a sense of beauty to begin with? A question we will never answer. Perhaps it’s just a kind of superfluity of sexual attraction. Nature needs us to feel drawn to other human bodies, but evolution is imprecise. In order to go far enough, to make that feeling strong enough, it went too far. Others are powerfully lovely to us, but so, in a strangely different, strangely similar way, are flowers and sunsets. Art, in turn, this line of thought might go, is a response to natural beauty. Stunned by it, we seek to rival it, to reproduce it, to prolong it. Flowers fade, sunsets melt from moment to moment; the love of bodies brings us grief. Art abides. “When old age shall this generational waste, / Thou shalt remain.”

Art is useless, said Wilde. Art is for art’s sake—that is, for beauty’s sake. But why do we possess a sense of beauty to begin with? A question we will never answer. Perhaps it’s just a kind of superfluity of sexual attraction. Nature needs us to feel drawn to other human bodies, but evolution is imprecise. In order to go far enough, to make that feeling strong enough, it went too far. Others are powerfully lovely to us, but so, in a strangely different, strangely similar way, are flowers and sunsets. Art, in turn, this line of thought might go, is a response to natural beauty. Stunned by it, we seek to rival it, to reproduce it, to prolong it. Flowers fade, sunsets melt from moment to moment; the love of bodies brings us grief. Art abides. “When old age shall this generational waste, / Thou shalt remain.” Many Americans, as far as I can tell, don’t want to shape their views in accordance with the data; many Americans, again as far as I can tell, don’t want to create an environment in which a broad range of perspectives are freely articulated and peacefully debated. They don’t want to be hopeful about the possibilities of America. Nor do they want academic freedom in our universities. What many people want, what they earnestly and passionately desire, is to hate their enemies. A few years ago J.D. Vance—now a senator, then a political neophyte—

Many Americans, as far as I can tell, don’t want to shape their views in accordance with the data; many Americans, again as far as I can tell, don’t want to create an environment in which a broad range of perspectives are freely articulated and peacefully debated. They don’t want to be hopeful about the possibilities of America. Nor do they want academic freedom in our universities. What many people want, what they earnestly and passionately desire, is to hate their enemies. A few years ago J.D. Vance—now a senator, then a political neophyte— Initially, it was suspected that gene regulation was a simple matter of one gene product acting as an on/off switch for another gene, in digital fashion. In the 1960s, the French biologists François Jacob and Jacques Monod first elucidated

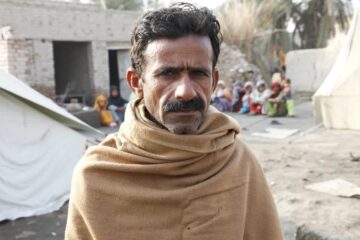

Initially, it was suspected that gene regulation was a simple matter of one gene product acting as an on/off switch for another gene, in digital fashion. In the 1960s, the French biologists François Jacob and Jacques Monod first elucidated  Pakistan is a vast country of 231.4 million people. It’s one of only nine countries in the world with nuclear weapons. It’s located in South Asia, which is now one of the world’s most dynamic and fast-growing regions. It has generally favorable relationships with both the United States and China. It has a long coastline in a generally peaceful region of the ocean. It has plenty of talented people, as evidenced by the fact that Pakistani Americans, on average,

Pakistan is a vast country of 231.4 million people. It’s one of only nine countries in the world with nuclear weapons. It’s located in South Asia, which is now one of the world’s most dynamic and fast-growing regions. It has generally favorable relationships with both the United States and China. It has a long coastline in a generally peaceful region of the ocean. It has plenty of talented people, as evidenced by the fact that Pakistani Americans, on average,  Much of the attention being paid to generative AI systems has focused on how they replicate the pathologies of already widely deployed AI systems, arguing that they centralise power and wealth, ignore copyright protections,

Much of the attention being paid to generative AI systems has focused on how they replicate the pathologies of already widely deployed AI systems, arguing that they centralise power and wealth, ignore copyright protections,