Category: Recommended Reading

Chita Rivera (1933 – 2024) Broadway Legend

Wayne Kramer (1948 – 2024) MC5 Guitarist

Saturday, February 3, 2024

Science does not describe reality

Bas van Fraassen makes the case in iai News:

When physicists present to each other at conferences they are all about mathematical models. The participants are deeply immersed in the abstract mathematical modelling. When on the other hand they present to the public it sounds all very understandable, about particles, waves, fields, and strings, quantum leaps and gravity. That is very helpful for mobilizing the imagination and an intuitive grasp on how phenomena or experiments look through theory-tinted glasses. But typically, it is also told as the one true story of the universe, its furniture and its workings. Is that how we should take it?

When physicists evaluate new models, hypotheses, or theories they are also immersed in theory. It goes like this: the theory says “I’ve designed a test you can do, a test based on how I represent the phenomena, and what I count as measurement procedures. Take me up on it, see if I pass! Put me to the question, bring it on!” And it is great news when the measurement results come in and the theory is borne out. That is empirical support for the theory. What precisely should we take away from this, seeing here the scientists’ own criteria of success in practice?

During the past hundred years or so philosophers of science have become more and more compartmentalized and specialized, but when it comes to general issues of science philosophers still divide roughly into empiricists and realists.

More here.

Unlearning Machines

Rob Lucas in Sidecar:

There is no denying the technological marvels that have resulted from the application of transformers in machine learning. They represent a step-change in a line of technical research that has spent most of its history looking positively deluded, at least to its more sober initiates. On the left, the critical reflex to see this as yet another turn of the neoliberal screw, or to point out the labour and resource extraction that underpin it, falls somewhat flat in the face of a machine that can, at last, interpret natural-language instructions fairly accurately, and fluently turn out text and images in response. Not long ago, such things seemed impossible. The appropriate response to these wonders is not dismissal but dread, and it is perhaps there that we should start, for this magic is overwhelmingly concentrated in the hands of a few often idiosyncratic people at the social apex of an unstable world power. It would obviously be foolhardy to entrust such people with the reified intelligence of humanity at large, but that is where we are.

Here in the UK, tech-addled university managers are currently advocating for overstretched teaching staff to turn to generative AI for the production of teaching materials. More than half of undergraduates are already using the same technology to help them write essays, and various AI platforms are being trialled for the automation of marking. Followed through to their logical conclusion, these developments would amount to a repurposing of the education system as a training process for privately owned machine learning models: students, teachers, lecturers all converted into a kind of outsourced administrator or technician, tending to the learning of a black-boxed ‘intelligence’ that does not belong to them.

More here.

Brand New India

Tim Sahay interviews Ravinder Kaur, author of Brand New Nation: Capitalist Dreams and Nationalist Designs in 21st Century India, in Polycrisis:

TIM SAHAY: Your book, Brand New Nation, looks at how countries were plugging into the liberal global economy of the 1990s to attract investment capital, and far from diminishing the importance of nation-states, rejuvenated ethno-nationalism. You’ve argued that in the Indian case, the “liberal” economy and “illiberal” hypernationalism of Modi’s BJP are not separate phenomena, but two strands of Hindutva’s vision. How would you characterize these connections?

RAVINDER KAUR: I begin my book in the 1990s, arguing that the last three decades of economic reforms basically transformed the nation into a commodity. I traced the ways in which India, the post colony, turned itself into an “emerging market.” Contrary to the understanding of globalization as a process imposed from the outside and resisted by local groups, I argue that economic “LPG” reforms—liberalization, privatization, globalization—were embraced by the policy elite in India. Initially, there was some political pushback against it, both within the BJP and Congress, but by the turn of the century, any resistance to them had disappeared.

This great transformation activated a seemingly unlikely alliance between global capitalism and hypernationalism, a foundation on which twenty-first century Hindu nationalism would begin taking shape.

More here.

The War Over Global Shipping

Over at Ones and Tooze:

The attacks by Houthi militants on cargo ships in and around the Red Sea is posing a serious threat to global trade—serious enough to prompt American-led air strikes on the group in Yemen. Thirty percent of all global containers pass through the Red Sea Strait. Adam and Cameron discuss the economic implications.

‘Hardy Women’ By Paula Byrne

Olivia Laing at The Guardian:

How Thomas Hardy would have hated this book. In his 70s, this most secretive of men burned old letters, diaries and manuscripts on a bonfire in his garden. His paranoia had been stoked by the publication of a critical biography. “Too personal, and in bad taste, even supposing it were true, which it is not!” he wrote indignantly in the margin.

How Thomas Hardy would have hated this book. In his 70s, this most secretive of men burned old letters, diaries and manuscripts on a bonfire in his garden. His paranoia had been stoked by the publication of a critical biography. “Too personal, and in bad taste, even supposing it were true, which it is not!” he wrote indignantly in the margin.

His solution was to seize control of the narrative with a sleight of hand designed to make it seem as if he wasn’t there at all. He wrote his own life story in the third person, to be published as a posthumous biography purportedly authored by his second wife, Florence. In it he made his position clear: “Poetry is emotion put into measure. The emotion must come by nature, but the measure can be acquired by art.”

more here.

The Life and Works of Martha Graham

Alexandra Jacobs at the NYT:

The choreographer’s collaborations were top-notch: the sculptor Isamu Noguchi; the composer Samuel Barber; and the designer Halston. Learning how she drew inspiration from so many disparate cultures (Greek, Indigenous, biblical) — with occasional gross insensitivity — one begins to realize that the term “modern dance,” like “classical music,” is if not a misnomer, then a massive oversimplification.

The choreographer’s collaborations were top-notch: the sculptor Isamu Noguchi; the composer Samuel Barber; and the designer Halston. Learning how she drew inspiration from so many disparate cultures (Greek, Indigenous, biblical) — with occasional gross insensitivity — one begins to realize that the term “modern dance,” like “classical music,” is if not a misnomer, then a massive oversimplification.

Critics could be “uncomprehending and denunciatory”; the public, “baffled but moved in some way they do not understand.” But Graham early on achieved one of the clearest marks of success: She was parodied. (By Fanny Brice, no less. And who can forget Robin Williams’s rapid-fire tour of American dance forms in “The Birdcage”?) Should she have gotten a piece of the Pulitzer that the composer Aaron Copland picked up for their ballet, “Appalachian Spring”? You bet your bottom Barbie.

more here.

The Martha Graham Technique

How to Fix America’s Shambolic Elections

Laura Thornton in Time Magazine:

For two decades in Asia and the former Soviet Union, I worked for democracy-promotion organizations, a central aim of which was bolstering democratic political parties. I trained them on internal party structure, platform development, constituent outreach, and, of course, candidate selection. With typical American hubris and pride, I often nudged parties toward the inclusive American primary system as a model for selecting candidates. “Primaries are the most inclusive and, theoretically, democratic,” I’d think to myself. “They allow everyday citizens to choose candidates rather than limiting this decision to party leaders.”

For two decades in Asia and the former Soviet Union, I worked for democracy-promotion organizations, a central aim of which was bolstering democratic political parties. I trained them on internal party structure, platform development, constituent outreach, and, of course, candidate selection. With typical American hubris and pride, I often nudged parties toward the inclusive American primary system as a model for selecting candidates. “Primaries are the most inclusive and, theoretically, democratic,” I’d think to myself. “They allow everyday citizens to choose candidates rather than limiting this decision to party leaders.”

Expanding candidate selection to include more stakeholders made perfect sense. In the countries where I worked, a small group of party leaders selected candidates without transparency or competition, frequently based on the candidate’s financial contributions. This opaque process failed to provide nominees who were representative of or accountable to the public, stifling the competition of ideas and values. Unsurprisingly, in turn, the public disdained parties and politics.

More here.

Saturday Poem

Packing the Kitchen Utensils

How many years since we used

the potato masher, the apple peeler,

its stainless-steel blade and crank

tucked in the back of the bottom

kitchen drawer among the balled

clot of discarded rubber bands?

And the egg slicer, never touched,

its grille and clean wires taut

as the silver foil outlines

of the invitations we mailed out

years ago? We bought these

utensils ourselves: hardly anyone

came to a gay wedding back then.

Which of you is the bride? someone

scrawled beneath the box checked

“decline.” At least they answered,

you said. Husband, I lift two nesting

spoons from the cutlery drawer,

wrap them in a grocery circular.

Though their silver oval faces

are tarnished with wear, on the handles

you can still make out the brand,

the words Lifetime Guarantee.

by Steve Bellin-Oka

from Split This Rock

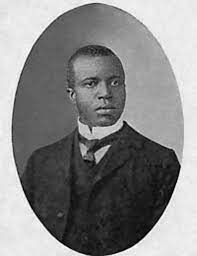

ragtime music

From the Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica:

Ragtime, propulsively syncopated musical style, one forerunner of jazz and the predominant style of American popular music from about 1899 to 1917. Ragtime evolved in the playing of honky-tonk pianists along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers in the last decades of the 19th century. It was influenced by minstrel-show songs, African American banjo styles, and syncopated (off-beat) dance rhythms of the cakewalk, and also elements of European music. Ragtime found its characteristic expression in formally structured piano compositions. The regularly accented left-hand beat, in or time, was opposed in the right hand by a fast, bouncingly syncopated melody that gave the music its powerful forward impetus.

Ragtime, propulsively syncopated musical style, one forerunner of jazz and the predominant style of American popular music from about 1899 to 1917. Ragtime evolved in the playing of honky-tonk pianists along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers in the last decades of the 19th century. It was influenced by minstrel-show songs, African American banjo styles, and syncopated (off-beat) dance rhythms of the cakewalk, and also elements of European music. Ragtime found its characteristic expression in formally structured piano compositions. The regularly accented left-hand beat, in or time, was opposed in the right hand by a fast, bouncingly syncopated melody that gave the music its powerful forward impetus.

Scott Joplin, called the “King of Ragtime,” published the most successful of the early rags, “The Maple Leaf Rag,” in 1899. Joplin, who considered ragtime a permanent and serious branch of classical music, composed hundreds of short pieces, a set of études, and operas in the style. Other important performers were, in St. Louis, Louis Chauvin and Thomas M. Turpin (father of St. Louis ragtime) and, in New Orleans, Tony Jackson.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Friday, February 2, 2024

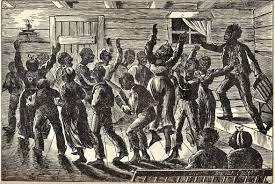

Before 1865

From Negro Spirituals:

The tunes and the beats of negro spirituals and Gospel songs are highly influenced by the music of their actual cultural environment. It means that their styles are continuously changing. The very first negro spirituals were inspired by African music even if the tunes were not far from those of hymns. Some of them, which were called “shouts” were accompanied with typical dancing including hand clapping and foot tapping.

The tunes and the beats of negro spirituals and Gospel songs are highly influenced by the music of their actual cultural environment. It means that their styles are continuously changing. The very first negro spirituals were inspired by African music even if the tunes were not far from those of hymns. Some of them, which were called “shouts” were accompanied with typical dancing including hand clapping and foot tapping.

SHOUTS

After a regular worship service, congregations used to stay for a “ring shout”. It was a survival of primitive African dance. So, educated ministers and members placed a ban on it. The men and women arranged themselves in a ring. The music started, perhaps with a Spiritual, and the ring began to move, at first slowly, then with quickening pace. The same musical phrase was repeated over and over for hours. This produced an ecstatic state. Women screamed and fell. Men, exhausted, dropped out of the ring.

Some African American religious singing at this time was referred as a “moan” (or a “groan”). Moaning (or groaning) does not imply pain. It is a kind of blissful rendition of a song, often mixed with humming and spontaneous melodic variation.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)

Rebecca Solnit: How to Comment on Social Media

Rebecca Solnit at Literary Hub:

1) Do not read the whole original post or what it links to, which will dilute the purity of your response and reduce your chances of rebuking the poster for not mentioning anything they might’ve mentioned/written a book on/devoted their life to. Listening/reading delays your reaction time, and as with other sports, speed is of the essence.

2) All of the O.P.’s feelings, experiences, interpretations, and values should be in the first sentence anyway. Only fascists hide those things in militarized outposts throughout the terrain of the piece. Which are basically ambushes. Which is violent and elitist.

3) If O.P. points out that your critique is baseless/ wrong/ high on its own fumes, whataboutism is your friend here. Just levy another charge, however unrelated. After all, any statement can be condemned for not including all other statements, aka O.P.’s concern about saving the whales is only a sign of his/her/their indifference about some other issue or cetacean or mammal or cause. There is always something.

More here.

For India’s Millions of Farm Workers, a ‘Drone Revolution’ Looms

Arbab Ali & Nadeem Sarwar in Undark:

Depending on the kind of sensor they’ve been armed with, drones can do a lot more than spray chemicals. Some can analyze the terrain for weeds, check moisture levels, assess for signs of pest infestation, suggest field planning, determine crop health, and even create a nutrient map of the growing harvest.

Depending on the kind of sensor they’ve been armed with, drones can do a lot more than spray chemicals. Some can analyze the terrain for weeds, check moisture levels, assess for signs of pest infestation, suggest field planning, determine crop health, and even create a nutrient map of the growing harvest.

But buying a drone is no small endeavor, even for financially sound farmers, and renting it out is also fraught with risks. A battery-powered drone costs the equivalent of $8,000, whereas a petrol-powered drone costs about $15,000 —and there are also insurance and damage fees to consider.

More here.

Republicans and Democrats consider each other immoral – even when treated fairly and kindly by the opposition

Phillip McGarry in The Conversation:

Psychology researcher Eli Finkel and his colleagues have suggested that moral judgment plays a major role in political polarization in the United States. My research team wondered if acts demonstrating good moral character could counteract partisan animosity. In other words, would you think more highly of someone who treated you well – regardless of their political leanings?

Psychology researcher Eli Finkel and his colleagues have suggested that moral judgment plays a major role in political polarization in the United States. My research team wondered if acts demonstrating good moral character could counteract partisan animosity. In other words, would you think more highly of someone who treated you well – regardless of their political leanings?

We decided to conduct an experiment based on game theory and turned to the Ultimatum Game, which researchers developed to study the role of fairness in cooperation. Psychology researcher Hanah Chapman and her colleagues have demonstrated that unfairness in the Ultimatum Game elicits moral disgust, making it a good tool for us to use to study moral judgment in real time.

The Ultimatum Game allowed us to experimentally manipulate whether partisans were treated unfairly, fairly or even kindly by political opponents. Participants had no knowledge about the person they were playing with beyond party affiliation and how they played the game.

More here.

Elon Musk: Last Week Tonight with John Oliver

On Wim Wenders’s “Anselm”

Yael Friedman at the LARB:

EARLY ON IN Wim Wenders’s new documentary Anselm, we hear the whispers of Anselm Kiefer’s famous headless female sculptures. “We may be the nameless and forgotten ones,” they whisper, “but we don’t forget a thing.” These full-bodied specters haunt us in the way only Kiefer’s art can. His body of work interrogates myth and memory, wrestling with Germany’s past in ways that helped form the foundation of its postwar present.

EARLY ON IN Wim Wenders’s new documentary Anselm, we hear the whispers of Anselm Kiefer’s famous headless female sculptures. “We may be the nameless and forgotten ones,” they whisper, “but we don’t forget a thing.” These full-bodied specters haunt us in the way only Kiefer’s art can. His body of work interrogates myth and memory, wrestling with Germany’s past in ways that helped form the foundation of its postwar present.

Both Wenders and Kiefer, two of Germany’s most iconic artists, were born in 1945, into the still-smoldering ruins of the war. Their engagement with the heaviness of history, and the “great silence” of the adults after the war, took dramatically different forms. Kiefer confronted it relentlessly, even bombastically, while Wenders has been guided by it more obliquely. In my recent conversation with Wenders, the filmmaker acknowledged that the two of them “had a very different approach—I wanted to leave it behind, and Anselm wanted to dig into it and put his finger on it. And that is also why I felt we had something to do together.”

more here.