Elie Dolgin in Nature:

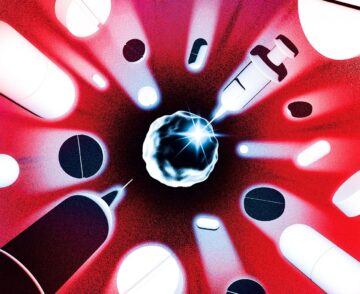

The blood cancer had returned, and Kevin Sander was running out of treatment options. A stem-cell transplant would offer the best chance for long-term survival, but to qualify for the procedure he would first need to reduce the extent of his tumour — a seemingly insurmountable goal, because successive treatments had all failed to keep the disease in check. As a last throw of the dice, he joined a landmark clinical trial. Led by haematologist Philipp Staber at the Medical University of Vienna, the study is exploring an innovative treatment strategy in which drugs are tested on the patient’s own cancer cells, cultured outside the body. In February 2022, researchers tried 130 compounds on cells grown from Sander’s cancer — essentially trying everything at their disposal to see what might work.

The blood cancer had returned, and Kevin Sander was running out of treatment options. A stem-cell transplant would offer the best chance for long-term survival, but to qualify for the procedure he would first need to reduce the extent of his tumour — a seemingly insurmountable goal, because successive treatments had all failed to keep the disease in check. As a last throw of the dice, he joined a landmark clinical trial. Led by haematologist Philipp Staber at the Medical University of Vienna, the study is exploring an innovative treatment strategy in which drugs are tested on the patient’s own cancer cells, cultured outside the body. In February 2022, researchers tried 130 compounds on cells grown from Sander’s cancer — essentially trying everything at their disposal to see what might work.

One option looked promising. It was a type of kinase inhibitor that is approved to treat thyroid cancer, but it is seldom, if ever, used for the rare subtype of lymphoma that Sander had. Physicians prescribed him a treatment regimen that included the drug, and it worked. The cancer receded, enabling him to undergo the stem-cell transplant. He has been in remission ever since. “I’m a bit more free now,” says Sander, a 38-year-old procurement manager living in Podersdorf am See, Austria. ”I do not fear death any more,” he adds. “I try to enjoy my life.” His story is a testament to this kind of intensive and highly personalized drug-screening method, referred to as functional precision medicine. Like all precision medicine, it aims to match treatments to patients, but it differs from the genomics-guided paradigm that has come to dominate the field. Instead of relying on genetic data and the best available understanding of tumour biology to select a treatment, clinicians throw everything they’ve got at cancer cells in the laboratory and see what sticks.

More here.

If a cow said, ‘Don’t eat me’, we wouldn’t. We seem to regard the capacity for language (by which we mean our kind of language) as evidence of moral significance. But do animals talk? Many traditions assume they do, and understanding animal talk has sometimes been thought to indicate great human wisdom. The proverbially wise Solomon understood the language of the birds, and St Francis preached to them. Most of us have asked what a crow’s squawk or a dog’s whine means. Perhaps we ask because we feel that animals can tell us something we don’t know about the sort of place this world is.

If a cow said, ‘Don’t eat me’, we wouldn’t. We seem to regard the capacity for language (by which we mean our kind of language) as evidence of moral significance. But do animals talk? Many traditions assume they do, and understanding animal talk has sometimes been thought to indicate great human wisdom. The proverbially wise Solomon understood the language of the birds, and St Francis preached to them. Most of us have asked what a crow’s squawk or a dog’s whine means. Perhaps we ask because we feel that animals can tell us something we don’t know about the sort of place this world is.

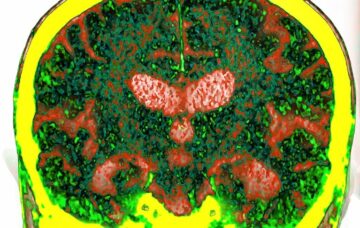

An analysis of around 1,500 blood proteins has identified biomarkers that can be used to predict the risk of developing dementia up to 15 years before diagnosis.

An analysis of around 1,500 blood proteins has identified biomarkers that can be used to predict the risk of developing dementia up to 15 years before diagnosis. When Tina Turner, years before she became rock ‘n’ roll royalty, lent her iconic voice to Phil Spector’s “River Deep, Mountain High” in 1966, the single ranked at No. 3 on the UK charts. But, on U.S. Billboard charts that same year, it didn’t get higher than 88. In the recent HBO documentary “Tina,” an archival clip of Ike Turner, who shares a credit for the song, explained that the song didn’t hold up in America because, during that time, “Black artists had to go Top 10 on the R&B charts before the top radio stations would touch it.” In the film, Ike added that the adventurous song, with its complex orchestration and lush, pop sound, was “too white for Black jockeys and too Black for white jockeys” in the U.S. Dan Lindsay, one of the co-directors of the documentary,

When Tina Turner, years before she became rock ‘n’ roll royalty, lent her iconic voice to Phil Spector’s “River Deep, Mountain High” in 1966, the single ranked at No. 3 on the UK charts. But, on U.S. Billboard charts that same year, it didn’t get higher than 88. In the recent HBO documentary “Tina,” an archival clip of Ike Turner, who shares a credit for the song, explained that the song didn’t hold up in America because, during that time, “Black artists had to go Top 10 on the R&B charts before the top radio stations would touch it.” In the film, Ike added that the adventurous song, with its complex orchestration and lush, pop sound, was “too white for Black jockeys and too Black for white jockeys” in the U.S. Dan Lindsay, one of the co-directors of the documentary,  SOMETIMES I STILL CAN’T BELIEVE

SOMETIMES I STILL CAN’T BELIEVE When Hannah Arendt looked at the man wearing an ill-fitting suit in the bulletproof dock inside a Jerusalem courtroom in 1961, she saw something different from everybody else. The prosecution, writes Lyndsey Stonebridge, ‘saw an ancient crime in modern garb, and portrayed Eichmann as the latest monster in the long history of anti-Semitism who had simply used novel methods to take hatred for Jews to a new level’. Arendt thought otherwise.

When Hannah Arendt looked at the man wearing an ill-fitting suit in the bulletproof dock inside a Jerusalem courtroom in 1961, she saw something different from everybody else. The prosecution, writes Lyndsey Stonebridge, ‘saw an ancient crime in modern garb, and portrayed Eichmann as the latest monster in the long history of anti-Semitism who had simply used novel methods to take hatred for Jews to a new level’. Arendt thought otherwise. In this second foray into the biology of death, I will examine programmed cell death or PCD. You might have heard of the process of apoptosis, but, as the previously reviewed

In this second foray into the biology of death, I will examine programmed cell death or PCD. You might have heard of the process of apoptosis, but, as the previously reviewed  In 1858, the great auk (Pinguinus impennis) was reported to be in serious decline. William Proctor, keeper of the bird collection at Durham University, had traveled to Iceland in 1833 and 1837, partly in order to seek out great auks, but reported that sightings were now rare in Iceland and that he had not seen any of the birds.

In 1858, the great auk (Pinguinus impennis) was reported to be in serious decline. William Proctor, keeper of the bird collection at Durham University, had traveled to Iceland in 1833 and 1837, partly in order to seek out great auks, but reported that sightings were now rare in Iceland and that he had not seen any of the birds. The Rebel’s Clinic thus enters an already crowded field. But given Fanon’s continuing influence, from the seminar room to social media to the streets, few would object to another effort to tell the story of his extraordinary life. Adam Shatz is well positioned to do so, since he has been writing about Fanon’s life and work for two decades (his first article on Fanon was

The Rebel’s Clinic thus enters an already crowded field. But given Fanon’s continuing influence, from the seminar room to social media to the streets, few would object to another effort to tell the story of his extraordinary life. Adam Shatz is well positioned to do so, since he has been writing about Fanon’s life and work for two decades (his first article on Fanon was

Recent years have seen successive waves of book bans in Republican-controlled states, aimed at pulling any text with “woke” themes from classrooms and library shelves. Though the results sometimes seem farcical, as with the banning of Art Spiegelman’s Maus due to its

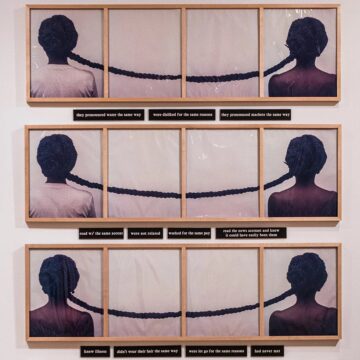

Recent years have seen successive waves of book bans in Republican-controlled states, aimed at pulling any text with “woke” themes from classrooms and library shelves. Though the results sometimes seem farcical, as with the banning of Art Spiegelman’s Maus due to its  From Zarastro Art:

From Zarastro Art: