Elie Dolgin in Nature:

The blood cancer had returned, and Kevin Sander was running out of treatment options. A stem-cell transplant would offer the best chance for long-term survival, but to qualify for the procedure he would first need to reduce the extent of his tumour — a seemingly insurmountable goal, because successive treatments had all failed to keep the disease in check. As a last throw of the dice, he joined a landmark clinical trial. Led by haematologist Philipp Staber at the Medical University of Vienna, the study is exploring an innovative treatment strategy in which drugs are tested on the patient’s own cancer cells, cultured outside the body. In February 2022, researchers tried 130 compounds on cells grown from Sander’s cancer — essentially trying everything at their disposal to see what might work.

The blood cancer had returned, and Kevin Sander was running out of treatment options. A stem-cell transplant would offer the best chance for long-term survival, but to qualify for the procedure he would first need to reduce the extent of his tumour — a seemingly insurmountable goal, because successive treatments had all failed to keep the disease in check. As a last throw of the dice, he joined a landmark clinical trial. Led by haematologist Philipp Staber at the Medical University of Vienna, the study is exploring an innovative treatment strategy in which drugs are tested on the patient’s own cancer cells, cultured outside the body. In February 2022, researchers tried 130 compounds on cells grown from Sander’s cancer — essentially trying everything at their disposal to see what might work.

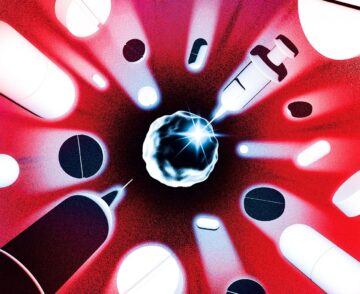

One option looked promising. It was a type of kinase inhibitor that is approved to treat thyroid cancer, but it is seldom, if ever, used for the rare subtype of lymphoma that Sander had. Physicians prescribed him a treatment regimen that included the drug, and it worked. The cancer receded, enabling him to undergo the stem-cell transplant. He has been in remission ever since. “I’m a bit more free now,” says Sander, a 38-year-old procurement manager living in Podersdorf am See, Austria. ”I do not fear death any more,” he adds. “I try to enjoy my life.” His story is a testament to this kind of intensive and highly personalized drug-screening method, referred to as functional precision medicine. Like all precision medicine, it aims to match treatments to patients, but it differs from the genomics-guided paradigm that has come to dominate the field. Instead of relying on genetic data and the best available understanding of tumour biology to select a treatment, clinicians throw everything they’ve got at cancer cells in the laboratory and see what sticks.

More here.