Gus O’Connor at The Nation:

At the height of his prominence, Luigi Pirandello was the principal darling of Italian drama. His plays were performed throughout Europe and the United States; Mussolini threw 700,000 lire at him when he decided to found an arts theater in Rome; and he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934, praised for his “bold and ingenious revival of dramatic and scenic art.” His acclaim was widespread: Jean-Paul Sartre hailed him as the most timely modern dramatist of the 20th century. And when Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot premiered in 1953 in Paris, the writer Jean Anouilh estimated that the evening at the Babylone Theater was “as important as the first Pirandello produced by [George] Pitoëf in Paris in 1923.” Jorge Luis Borges felt a great kinship with him; Thomas Bernhard namechecked him. How, then, did Pirandello end up a half-forgotten castaway of European letters by the 1980s? The answer, in part, appears straightforward: Pirandello was a fascist.

At the height of his prominence, Luigi Pirandello was the principal darling of Italian drama. His plays were performed throughout Europe and the United States; Mussolini threw 700,000 lire at him when he decided to found an arts theater in Rome; and he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934, praised for his “bold and ingenious revival of dramatic and scenic art.” His acclaim was widespread: Jean-Paul Sartre hailed him as the most timely modern dramatist of the 20th century. And when Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot premiered in 1953 in Paris, the writer Jean Anouilh estimated that the evening at the Babylone Theater was “as important as the first Pirandello produced by [George] Pitoëf in Paris in 1923.” Jorge Luis Borges felt a great kinship with him; Thomas Bernhard namechecked him. How, then, did Pirandello end up a half-forgotten castaway of European letters by the 1980s? The answer, in part, appears straightforward: Pirandello was a fascist.

Pirandello’s work betrayed a fascination with violence and its supposed power to cleanse society, and he approached his art with the attitude of giving form to chaos. His writing was popular, though, because of his highly developed style, which was characterized by a ceaseless desire to understand the world from the standpoint of the individual. Pirandello was startlingly modern: He committed himself to an ironic self-consciousness, to creating characters that struggled impossibly for individual freedom and to live up to their ideals.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

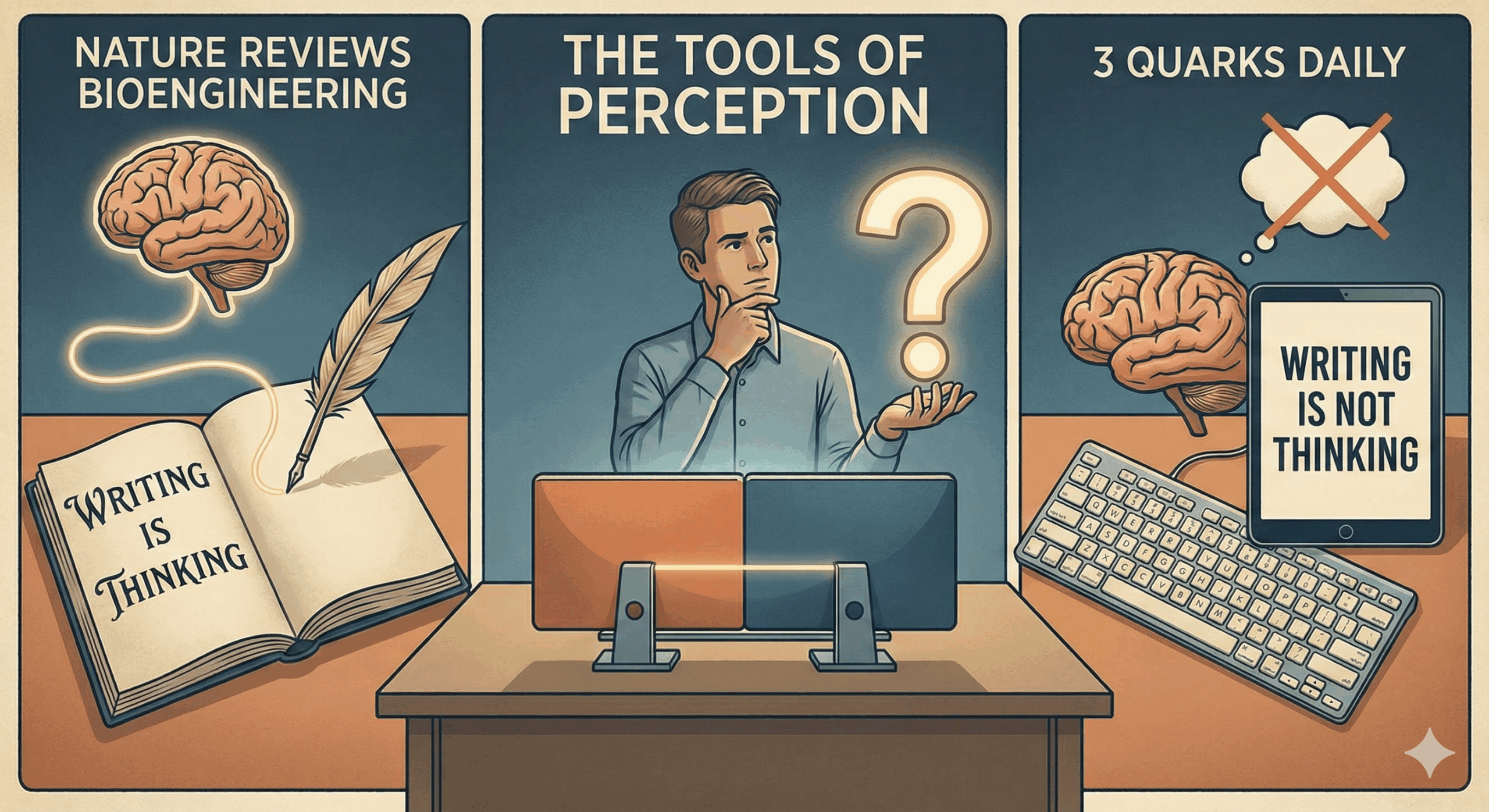

My science feeds have delivered two pieces this morning that arrive in productive tension. A June editorial in Nature Reviews Bioengineering declares that “Writing is Thinking,” calling for continued recognition of human-generated scientific writing in the age of large language models. A September essay in 3 Quarks Daily fires back with the counterpoint: “

My science feeds have delivered two pieces this morning that arrive in productive tension. A June editorial in Nature Reviews Bioengineering declares that “Writing is Thinking,” calling for continued recognition of human-generated scientific writing in the age of large language models. A September essay in 3 Quarks Daily fires back with the counterpoint: “ Large language models can be unreliable and say dumb things, but then, so can humans. Their strengths and weaknesses are certainly different from ours. But we are

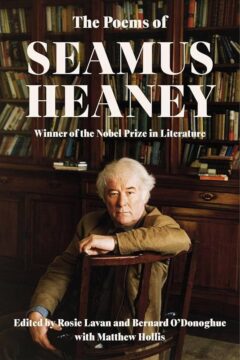

Large language models can be unreliable and say dumb things, but then, so can humans. Their strengths and weaknesses are certainly different from ours. But we are  “DEAR JEEM,” the poet Seamus Heaney wrote to his friend, the poet and novelist Seamus Deane, in 1966, as both writers’ careers were finding their runway, “Here are the proofs [of your poems …] have you anything else to bung in here?” That summer, Heaney was editing a chapbook of Deane’s poems for the Belfast Festival. The two writers had met in grammar school at ages 11 and 10, respectively, and remained close friends throughout their lives—Heaney going on to become a globally acclaimed poet, translator, and Nobel laureate, while Deane’s career as a scholar, critic, and editor helped to spearhead Irish studies as a disciplinary field.

“DEAR JEEM,” the poet Seamus Heaney wrote to his friend, the poet and novelist Seamus Deane, in 1966, as both writers’ careers were finding their runway, “Here are the proofs [of your poems …] have you anything else to bung in here?” That summer, Heaney was editing a chapbook of Deane’s poems for the Belfast Festival. The two writers had met in grammar school at ages 11 and 10, respectively, and remained close friends throughout their lives—Heaney going on to become a globally acclaimed poet, translator, and Nobel laureate, while Deane’s career as a scholar, critic, and editor helped to spearhead Irish studies as a disciplinary field. INTERVIEWER

INTERVIEWER Giving students an occasion to discover the divergence between the depth of the conservative intellectual tradition and the shallowness of the contemporary online right is one of the major attractions of teaching conservatism for one of our session leaders, Emory’s Frank Lechner. Lechner

Giving students an occasion to discover the divergence between the depth of the conservative intellectual tradition and the shallowness of the contemporary online right is one of the major attractions of teaching conservatism for one of our session leaders, Emory’s Frank Lechner. Lechner A

A She certainly doesn’t want to be idolised as a saint – that rarely ends well, and besides, she holds grudges. She even chafes against her mantle as feminist icon, “expected to do the Right Thing for women in all circumstances, with many different Right Things projected on to me from readers and viewers”, as she writes in Book of Lives.

She certainly doesn’t want to be idolised as a saint – that rarely ends well, and besides, she holds grudges. She even chafes against her mantle as feminist icon, “expected to do the Right Thing for women in all circumstances, with many different Right Things projected on to me from readers and viewers”, as she writes in Book of Lives.

As Michael Billington put it in a

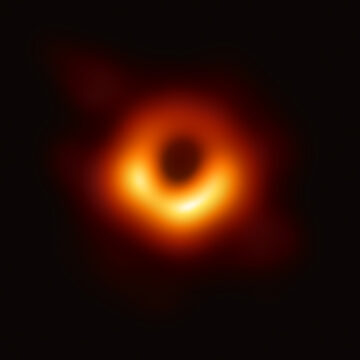

As Michael Billington put it in a  What came first, the chicken or the egg? Perhaps a silly conundrum already solved by Darwinian biology. But nature has supplied us with a real version of this puzzle: black holes. Within these cosmic objects, the extreme warping of spacetime brings past and future together, making it hard to tell what came first. Black holes also blur the distinction between matter and energy, fusing them into a single entity. In this sense, they also warp our everyday intuitions about space, time and causality, making them both chicken and egg at once.

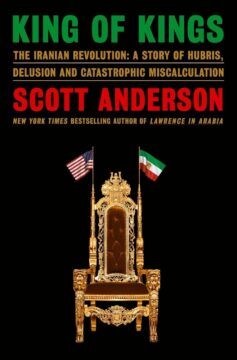

What came first, the chicken or the egg? Perhaps a silly conundrum already solved by Darwinian biology. But nature has supplied us with a real version of this puzzle: black holes. Within these cosmic objects, the extreme warping of spacetime brings past and future together, making it hard to tell what came first. Black holes also blur the distinction between matter and energy, fusing them into a single entity. In this sense, they also warp our everyday intuitions about space, time and causality, making them both chicken and egg at once. Scott Anderson begins his latest book, King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution; A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation (2025), with the story of an infamous 1971 party in a desert. The king of Anderson’s title, Iran’s shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was ostensibly marking 2,500 years of the Persian empire in Persepolis, once the capital under Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid Empire around 550 BCE. At a time of political stress, the shah was making a bid to link the Pahlavi dynasty, and himself in particular, to Cyrus, as the basis of an unquestionable legitimacy—“his rule and his achievements forming a continuum with those of the ancient immortals,” in Anderson’s words.

Scott Anderson begins his latest book, King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution; A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation (2025), with the story of an infamous 1971 party in a desert. The king of Anderson’s title, Iran’s shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was ostensibly marking 2,500 years of the Persian empire in Persepolis, once the capital under Cyrus the Great, who founded the Achaemenid Empire around 550 BCE. At a time of political stress, the shah was making a bid to link the Pahlavi dynasty, and himself in particular, to Cyrus, as the basis of an unquestionable legitimacy—“his rule and his achievements forming a continuum with those of the ancient immortals,” in Anderson’s words. The curiosity that drove the Irish novelist Maggie O’Farrell to write her bestselling 2020 novel Hamnet sprang from the scarcity of documentation about the book’s title character, Hamnet Shakespeare. Born in 1585 to William and Anne Shakespeare, the twin brother to a girl named Judith, Hamnet died of unknown causes in 1596, the only one of the Shakespeares’ three children not to reach adulthood. But for the records of his christening and his burial in the Stratford-upon-Avon parish registers, Hamnet’s 11 years on earth remain a tantalizing blank, one of those countless human existences that are legible to us now only in the form of a bookended pair of dates.

The curiosity that drove the Irish novelist Maggie O’Farrell to write her bestselling 2020 novel Hamnet sprang from the scarcity of documentation about the book’s title character, Hamnet Shakespeare. Born in 1585 to William and Anne Shakespeare, the twin brother to a girl named Judith, Hamnet died of unknown causes in 1596, the only one of the Shakespeares’ three children not to reach adulthood. But for the records of his christening and his burial in the Stratford-upon-Avon parish registers, Hamnet’s 11 years on earth remain a tantalizing blank, one of those countless human existences that are legible to us now only in the form of a bookended pair of dates.