Gus O’Connor at The Nation:

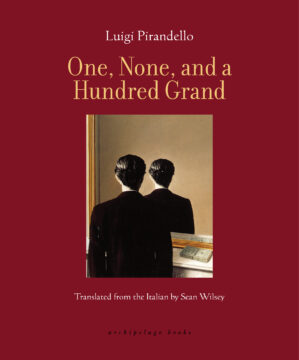

At the height of his prominence, Luigi Pirandello was the principal darling of Italian drama. His plays were performed throughout Europe and the United States; Mussolini threw 700,000 lire at him when he decided to found an arts theater in Rome; and he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934, praised for his “bold and ingenious revival of dramatic and scenic art.” His acclaim was widespread: Jean-Paul Sartre hailed him as the most timely modern dramatist of the 20th century. And when Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot premiered in 1953 in Paris, the writer Jean Anouilh estimated that the evening at the Babylone Theater was “as important as the first Pirandello produced by [George] Pitoëf in Paris in 1923.” Jorge Luis Borges felt a great kinship with him; Thomas Bernhard namechecked him. How, then, did Pirandello end up a half-forgotten castaway of European letters by the 1980s? The answer, in part, appears straightforward: Pirandello was a fascist.

At the height of his prominence, Luigi Pirandello was the principal darling of Italian drama. His plays were performed throughout Europe and the United States; Mussolini threw 700,000 lire at him when he decided to found an arts theater in Rome; and he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934, praised for his “bold and ingenious revival of dramatic and scenic art.” His acclaim was widespread: Jean-Paul Sartre hailed him as the most timely modern dramatist of the 20th century. And when Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot premiered in 1953 in Paris, the writer Jean Anouilh estimated that the evening at the Babylone Theater was “as important as the first Pirandello produced by [George] Pitoëf in Paris in 1923.” Jorge Luis Borges felt a great kinship with him; Thomas Bernhard namechecked him. How, then, did Pirandello end up a half-forgotten castaway of European letters by the 1980s? The answer, in part, appears straightforward: Pirandello was a fascist.

Pirandello’s work betrayed a fascination with violence and its supposed power to cleanse society, and he approached his art with the attitude of giving form to chaos. His writing was popular, though, because of his highly developed style, which was characterized by a ceaseless desire to understand the world from the standpoint of the individual. Pirandello was startlingly modern: He committed himself to an ironic self-consciousness, to creating characters that struggled impossibly for individual freedom and to live up to their ideals.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.