Walker Mimms at n+1:

In McCarthy’s novels, people commit terrible acts—necrophilia, infanticide, cannibalism—and often with reason. His villains are symbols of that dark reason: the trio of swampland marauders in Outer Dark (1968), the dream-curdling scalp-hunter in Blood Meridian, the frigid bounty hunter stalking No Country. In The Passenger and Stella Maris, McCarthy tops this rap sheet with his worst crime yet: nuclear Armageddon. And the perp is one of American history’s finest minds, the porkpie-hatted architect of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In McCarthy’s novels, people commit terrible acts—necrophilia, infanticide, cannibalism—and often with reason. His villains are symbols of that dark reason: the trio of swampland marauders in Outer Dark (1968), the dream-curdling scalp-hunter in Blood Meridian, the frigid bounty hunter stalking No Country. In The Passenger and Stella Maris, McCarthy tops this rap sheet with his worst crime yet: nuclear Armageddon. And the perp is one of American history’s finest minds, the porkpie-hatted architect of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Though it isn’t Armageddon exactly. The Passenger is a historical novel set in 1980, and the world is still very much alive. The mere possibility of apocalypse by human means is crime enough. Throughout the novel, Bobby Western, a 36-year-old salvage diver and racecar driver, is haunted by his upbringing near the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, and in Los Alamos, New Mexico, two places where his physicist father, a protégé of Oppenheimer, helped design the device that would devastate Hiroshima in 1945.

more here.

H

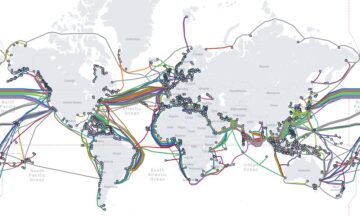

H Have you ever wondered how an email sent from New York arrives in Sydney in mere seconds, or how you can video chat with someone on the other side of the globe with barely a hint of delay? Behind these everyday miracles lies an unseen, sprawling web of undersea cables, quietly powering the instant global communications that people have come to rely on.

Have you ever wondered how an email sent from New York arrives in Sydney in mere seconds, or how you can video chat with someone on the other side of the globe with barely a hint of delay? Behind these everyday miracles lies an unseen, sprawling web of undersea cables, quietly powering the instant global communications that people have come to rely on. But single expressions are merely “pieces of a man,” as Adam Shatz, quoting Gil Scott-Heron, observes in The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon. In this timely and engaging new book—the first full-length biography in English since David Macey’s in 2000—Shatz restores a sense of wholeness to Fanon’s life and work. The unifying pursuit of Fanon’s life, Shatz argues, was the “disalienation” of those suffering from racial and colonial oppression—a project at once individual and social, clinical as well as political. For Fanon, Shatz concludes, this was the end goal of psychiatry as a practice of freedom.

But single expressions are merely “pieces of a man,” as Adam Shatz, quoting Gil Scott-Heron, observes in The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon. In this timely and engaging new book—the first full-length biography in English since David Macey’s in 2000—Shatz restores a sense of wholeness to Fanon’s life and work. The unifying pursuit of Fanon’s life, Shatz argues, was the “disalienation” of those suffering from racial and colonial oppression—a project at once individual and social, clinical as well as political. For Fanon, Shatz concludes, this was the end goal of psychiatry as a practice of freedom. Beyoncé

Beyoncé Heavy industry is one of the most stubbornly difficult areas of the economy to decarbonize. But new research suggests emissions could be reduced by up to 85 percent globally using a mixture of tried-and-tested and upcoming technologies. While much of the climate debate focuses on areas like electricity, vehicle emissions, and aviation, a huge fraction of carbon emissions comes from hidden industrial processes. In 2022, the sector—which includes things like chemicals, iron and steel, and cement—accounted for a quarter of the world’s emissions,

Heavy industry is one of the most stubbornly difficult areas of the economy to decarbonize. But new research suggests emissions could be reduced by up to 85 percent globally using a mixture of tried-and-tested and upcoming technologies. While much of the climate debate focuses on areas like electricity, vehicle emissions, and aviation, a huge fraction of carbon emissions comes from hidden industrial processes. In 2022, the sector—which includes things like chemicals, iron and steel, and cement—accounted for a quarter of the world’s emissions,  “DID PORN KILL feminism?” asked Amia Srinivasan in her widely read book The Right to Sex (2021). In the internet age, it sure can look that way. As Srinivasan pointed out, top commercial porn sites host billions of visitors every month. Today’s college students grew up with those sites just a click away. Many had their first sexual experiences in front of a computer screen. When she talked with her own college students, she saw the consequences:

“DID PORN KILL feminism?” asked Amia Srinivasan in her widely read book The Right to Sex (2021). In the internet age, it sure can look that way. As Srinivasan pointed out, top commercial porn sites host billions of visitors every month. Today’s college students grew up with those sites just a click away. Many had their first sexual experiences in front of a computer screen. When she talked with her own college students, she saw the consequences: Best Bees is one of the many companies carving out a niche in a commercial landscape increasingly focused on advertising environmental responsibility, pushed by both customer demand and regulatory requirements. Testing environmental DNA, which allows data to be gathered from the tiny pieces of skin, scales, and slime that species shed as they move through the world, has been framed as a cheap and efficient way to understand a corporation’s impact.

Best Bees is one of the many companies carving out a niche in a commercial landscape increasingly focused on advertising environmental responsibility, pushed by both customer demand and regulatory requirements. Testing environmental DNA, which allows data to be gathered from the tiny pieces of skin, scales, and slime that species shed as they move through the world, has been framed as a cheap and efficient way to understand a corporation’s impact. Yascha Mounk: It’s always a pleasure to have you on the podcast and particularly when you have an important new book which you have just published called

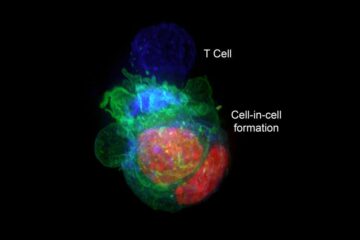

Yascha Mounk: It’s always a pleasure to have you on the podcast and particularly when you have an important new book which you have just published called  In a surprise discovery, researchers found that cells from some types of cancers escaped destruction by the immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells. The finding, they suggested in

In a surprise discovery, researchers found that cells from some types of cancers escaped destruction by the immune system by hiding inside other cancer cells. The finding, they suggested in  The

The

The Port of Baltimore was on a roll. In February, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore celebrated new

The Port of Baltimore was on a roll. In February, Maryland Gov. Wes Moore celebrated new  Of course, autocrats always tout their achievements, or insist that their regimes rest on the will of the people. Even Nazi Germany claimed popular legitimacy, a racist and anti-Semitic Volks-sovereignty. Soviet apologists and fellow travelers labeled Stalin’s Eastern European vassal states “people’s democracies.” The contemporary narrative seems depressingly familiar. Even so, the specter of powerful autocratic states that parasitically mimic democracy, while in reality eviscerating its core, should alarm us. Are democracy’s rivals indeed gaining ground? And, what precisely is different this time?

Of course, autocrats always tout their achievements, or insist that their regimes rest on the will of the people. Even Nazi Germany claimed popular legitimacy, a racist and anti-Semitic Volks-sovereignty. Soviet apologists and fellow travelers labeled Stalin’s Eastern European vassal states “people’s democracies.” The contemporary narrative seems depressingly familiar. Even so, the specter of powerful autocratic states that parasitically mimic democracy, while in reality eviscerating its core, should alarm us. Are democracy’s rivals indeed gaining ground? And, what precisely is different this time?