Martin Tyrrell at the Dublin Review of Books:

Eileen O’Shaughnessy married George Orwell in 1936 and remained married to him until her unexpected and untimely death in 1945. Anna Funder’s Wifedom is primarily an analysis of that nine-year marriage, which Funder concludes as having been throughout to Eileen’s disadvantage, an ‘arms race to mutual self-destruction: she by selflessness, and he by disappearing into the greedy double life that is the artist’s, of self + work’. The Orwell that emerges from this account was variously exploitative, neglectful, hypocritical and adulterous, not to mention a tepid and unremarkable lover and, who knows, a tortured and in-denial homosexual. Separate from his life with Eileen he was an inept seducer, occasional stalker, and, on at least two occasions, thwarted rapist.

Eileen O’Shaughnessy married George Orwell in 1936 and remained married to him until her unexpected and untimely death in 1945. Anna Funder’s Wifedom is primarily an analysis of that nine-year marriage, which Funder concludes as having been throughout to Eileen’s disadvantage, an ‘arms race to mutual self-destruction: she by selflessness, and he by disappearing into the greedy double life that is the artist’s, of self + work’. The Orwell that emerges from this account was variously exploitative, neglectful, hypocritical and adulterous, not to mention a tepid and unremarkable lover and, who knows, a tortured and in-denial homosexual. Separate from his life with Eileen he was an inept seducer, occasional stalker, and, on at least two occasions, thwarted rapist.

In contrast, Eileen gave up her promising career in educational psychology to share his spartan lifestyle in a shack in Wallington. There she toiled at the mundane while he worked endlessly on writings that paid little, at least during his and her lifetime.

more here.

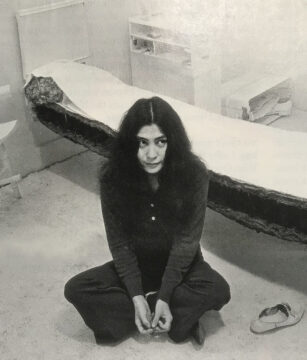

Halfway round the new “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” exhibition at Tate Modern (on until 1 September) I enter into a kind of record-shop listening booth that is decorated with her album covers and filled with individual sets of headphones. It’s the least crowded section of the show – Yoko’s music still perhaps not being people’s favourite thing about her – but I’m happy that her records are included here. So I put on a song I love, “Death of Samantha”, from 1973.

Halfway round the new “Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind” exhibition at Tate Modern (on until 1 September) I enter into a kind of record-shop listening booth that is decorated with her album covers and filled with individual sets of headphones. It’s the least crowded section of the show – Yoko’s music still perhaps not being people’s favourite thing about her – but I’m happy that her records are included here. So I put on a song I love, “Death of Samantha”, from 1973. Can’t tell you what

Can’t tell you what  Under cover of darkness, I boarded a Navy vessel at a heavily guarded military base along the Eastern Seaboard. The location and time of departure, as well as the direction and distance of travel, were unknown to me. Adding to the sense of secrecy, a towering sailor in camouflage stood in the rain, examining my belongings for electronics that might leave a digital trail an adversary could intercept and exploit.

Under cover of darkness, I boarded a Navy vessel at a heavily guarded military base along the Eastern Seaboard. The location and time of departure, as well as the direction and distance of travel, were unknown to me. Adding to the sense of secrecy, a towering sailor in camouflage stood in the rain, examining my belongings for electronics that might leave a digital trail an adversary could intercept and exploit. “Was it a government action, or did they do it themselves because of pressure?”

“Was it a government action, or did they do it themselves because of pressure?” READING DAVID THOMSON’S new book about television, Remotely: Travels in the Binge of TV, I remembered a beguiling moment in his 2016 history of the medium, Television: A Biography. At the end of that book, Thomson includes a photograph of a young man at a trade show with his eyes—the entire top of his head, in fact—covered by black virtual-reality glasses. The image exudes a dopey cheerlessness, as if his high-tech leisure-seeking has annulled the poor guy himself. Or is the feeling even worse—blunt menace, as if this man were some futuristic Cyclops? Under

READING DAVID THOMSON’S new book about television, Remotely: Travels in the Binge of TV, I remembered a beguiling moment in his 2016 history of the medium, Television: A Biography. At the end of that book, Thomson includes a photograph of a young man at a trade show with his eyes—the entire top of his head, in fact—covered by black virtual-reality glasses. The image exudes a dopey cheerlessness, as if his high-tech leisure-seeking has annulled the poor guy himself. Or is the feeling even worse—blunt menace, as if this man were some futuristic Cyclops? Under  When I began writing a novel about adolescence in Shanghai, I knew rooftopping would weave into its fabric. I didn’t personally know any rooftoppers, but the mentality that drove so many young men to take up

When I began writing a novel about adolescence in Shanghai, I knew rooftopping would weave into its fabric. I didn’t personally know any rooftoppers, but the mentality that drove so many young men to take up  Eye diseases

Eye diseases One of the greatest of all American books, Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” was published by Random House sixty years ago, on April 14, 1952, and became an immediate sensation. Almost everyone who cared about such things knew that something remarkable had happened. Ellison, a passionate reader of Twain, Dostoyevsky, Faulkner, Hemingway, Joyce, Malraux, T. S. Eliot, and Richard Wright, had marshalled a good part of the literary past and broken new ground as a novelist. His novel moves back and forth between stern realism and fantasia, despair and rhapsody, formal syntax and jazzy, impassioned riffs. Ellison pushed black folklore into surrealism and play—both sombre play and the most exuberant shenanigans.

One of the greatest of all American books, Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” was published by Random House sixty years ago, on April 14, 1952, and became an immediate sensation. Almost everyone who cared about such things knew that something remarkable had happened. Ellison, a passionate reader of Twain, Dostoyevsky, Faulkner, Hemingway, Joyce, Malraux, T. S. Eliot, and Richard Wright, had marshalled a good part of the literary past and broken new ground as a novelist. His novel moves back and forth between stern realism and fantasia, despair and rhapsody, formal syntax and jazzy, impassioned riffs. Ellison pushed black folklore into surrealism and play—both sombre play and the most exuberant shenanigans. The requests from independent journalists for grants, including personal emergency grants, have been coming in extra fast lately. Receiving them, me and my staff at the

The requests from independent journalists for grants, including personal emergency grants, have been coming in extra fast lately. Receiving them, me and my staff at the

In late 1936 George Orwell, like so many young idealists from Europe and the USA, went off to fight fascism in Spain. By the spring of 1937 he realized he was in a war with not two but three sides. The USSR was holding back a full Spanish revolution while attacking the socialists and anarchists outside its control.

In late 1936 George Orwell, like so many young idealists from Europe and the USA, went off to fight fascism in Spain. By the spring of 1937 he realized he was in a war with not two but three sides. The USSR was holding back a full Spanish revolution while attacking the socialists and anarchists outside its control. Language is a universal and democratic fact cutting across all human societies: no human group is without it, and no language is superior to any other. More than race or religion, language is a window on to the deepest levels of human diversity. The familiar map of the world’s 200 or so nation-states is superficial compared with the little-known map of its

Language is a universal and democratic fact cutting across all human societies: no human group is without it, and no language is superior to any other. More than race or religion, language is a window on to the deepest levels of human diversity. The familiar map of the world’s 200 or so nation-states is superficial compared with the little-known map of its