David Denby in The New Yorker:

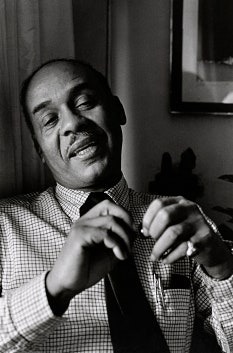

One of the greatest of all American books, Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” was published by Random House sixty years ago, on April 14, 1952, and became an immediate sensation. Almost everyone who cared about such things knew that something remarkable had happened. Ellison, a passionate reader of Twain, Dostoyevsky, Faulkner, Hemingway, Joyce, Malraux, T. S. Eliot, and Richard Wright, had marshalled a good part of the literary past and broken new ground as a novelist. His novel moves back and forth between stern realism and fantasia, despair and rhapsody, formal syntax and jazzy, impassioned riffs. Ellison pushed black folklore into surrealism and play—both sombre play and the most exuberant shenanigans.

One of the greatest of all American books, Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” was published by Random House sixty years ago, on April 14, 1952, and became an immediate sensation. Almost everyone who cared about such things knew that something remarkable had happened. Ellison, a passionate reader of Twain, Dostoyevsky, Faulkner, Hemingway, Joyce, Malraux, T. S. Eliot, and Richard Wright, had marshalled a good part of the literary past and broken new ground as a novelist. His novel moves back and forth between stern realism and fantasia, despair and rhapsody, formal syntax and jazzy, impassioned riffs. Ellison pushed black folklore into surrealism and play—both sombre play and the most exuberant shenanigans.

Explicitly, he rejected the limited point-of-view strategies of Henry James and the stylized austerity and gruffness of the hard-boiled writers. “Invisible Man” is a tumultuous book, an enormous book, liberated and responsible at the same time, a novel that, even now, turns readers upside down. I’ve just read it with a group of eleventh-graders in New York who seemed a little overwhelmed, at times, but, under the guidance of a good teacher (not me; a pro), they hung in there and did well by it. Ellison presents American experience with a luscious eloquence and an abandon corralled by a stern sense of form, and the students responded to both the wildness and the control.

More here. (Note: In honor of Black History Month, at least one post will be devoted to its 2024 theme of “African Americans and the Arts” throughout the month of February)