Category: Recommended Reading

Thomas Gumbleton (1930 – 2024) Bishop and Social Activist

Sunday Poem

Elevator Music

A tune with no more substance than the air,

performed on underwater instruments,

is proper for this short lift from the earth.

It hovers as we draw into ourselves

and turn our reverent eyes toward the lights

that count us to our various destinies.

We’re all in this together, the song says,

and later we’ll descend. The melody

is like a name we don’t recall just now

that still keeps on insisting it is there.

by Henry Taylor

from Poetry 180

Random House 2003

Saturday, April 13, 2024

Crimes Against Language

Sarah Aziza in The Baffler:

THERE IS NO PROPER ENTRANCE to an essay that undertakes things which should never be uttered, which have already been said. There is no way to reconcile the knowledge that the hours I spend writing will also mark the death of numerous Palestinians, and an endless interval of hunger and agony for many more. For Palestinians in the diaspora, there is no body but the uncanny body now—this set of bones and skin which I have inexplicably been granted, while so many others languish, rupture, decay. In New York City, I watch the tree outside my window flicker into bloom, and I shudder at this sign of spring. It is the advent of the third season, and the seventh month, of the Gaza genocide.

In the beginning—the chilled and chilling autumn when the annihilation commenced—time moved like an accordion. Interminable nights, bitter-bright mornings, weekends compressed with urgency. I burned with an electric grief, my veins timed to the hammer-pulse of war. With millions around the world, I read our death, wrote our death, protested our death, measuring each hour in corpses, in outrage and fear. The enduring Zionist fantasy—to finish the job, to solve the Palestinian question—hulked on the horizon, a rapacious body, steel-toothed and single-willed. In its path, the last, fragile membrane of Western pretense, which, for all its hypocrisies, still feigned belief in red lines, in keeping up appearances of restraint.

On the knife’s edge, not only Gaza, but all of us.

More here.

The Electric Vehicle Developmental State

Paolo Gerbaudo in Phenomenal World:

In the late 1970s, Western markets were flooded with Japanese cars from then-unfamiliar brands like Toyota, Mazda, Datsun, and Honda. The combination of a high quality product, efficient fuel consumption, and a low price tag made these brands very popular in the US and Europe in the aftermath of the 1970s oil shock, resulting in a decline in market share for domestic manufacturers and complaints of unfair competition from entrepreneurs and trade unions.

The “Japan Shock” soon engendered a protectionist policy response. The US and the UK negotiated voluntary import quotas with Japan to limit competitive pressure on their car industries, and European countries adopted similar measures. But this was only the first step in a deeper transformation of Western industry. Desperately seeking avenues to regain international competitiveness and quell heightening domestic labor unrest, companies in the global automotive sector and beyond began to emulate their Japanese rivals. The “Toyota method,” expounded by the company’s leading industrial engineer Taiichi Ohno, became a must-read for any serious industrial manager, while North Atlantic business schools started teaching Kaizen and Kanban methods of “just-in-time” production. This cultural shift, sometimes described as part of a broader process of “Japanization,” served to catalyze the embrace of what sociologists came to call post-Fordist management strategies, which focused on flexibility and cost-cutting while rejecting the vertically integrated production models of 1950s US and European auto leaders.

Nearly fifty years after the “Japan shock,” today’s global automotive industry confronts a far more systemic upheaval—what we could term the “Chinese electric vehicle (EV) shock.” Until recently, China’s automotive industry was dismissed as a low-quality copy of Western or Japanese models. However, it has since achieved impressive quality and price competitiveness in the strategic section of electric vehicles—in 2023, the Chinese giant BYD overtook Tesla as the largest producer of electric cars with 3 million New Energy Vehicles (NEVs). That year, China’s export of NEVs grew by 64 percent. Together with good Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) sales and Russian demand induced by Western sanctions, China has already overcome Japan as the world’s largest auto exporter overall.

More here.

The Shoah After Gaza

Adam Shatz interviews Pankaj Mishra in the LRB Podcast:

Pankaj Mishra joins Adam Shatz to discuss his recent LRB Winter Lecture, in which he explores Israel’s instrumentalisation of the Holocaust. He expands on his readings of Jean Améry and Primo Levi, the crisis as understood by the Global South and Zionism’s appeal for Hindu nationalists.

You can read The Shoah After Gaza in the LRB archive, or watch the lecture via the LRB YouTube channel. From The Shoah After Gaza:

In 1977, a year before he killed himself, the Austrian writer Jean Améry came across press reports of the systematic torture of Arab prisoners in Israeli prisons. Arrested in Belgium in 1943 while distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets, Améry himself had been brutally tortured by the Gestapo, and then deported to Auschwitz. He managed to survive, but could never look at his torments as things of the past. He insisted that those who are tortured remain tortured, and that their trauma is irrevocable. Like many survivors of Nazi death camps, Améry came to feel an ‘existential connection’ to Israel in the 1960s. He obsessively attacked left-wing critics of the Jewish state as ‘thoughtless and unscrupulous’, and may have been one of the first to make the claim, habitually amplified now by Israel’s leaders and supporters, that virulent antisemites disguise themselves as virtuous anti-imperialists and anti-Zionists. Yet the ‘admittedly sketchy’ reports of torture in Israeli prisons prompted Améry to consider the limits of his solidarity with the Jewish state. In one of the last essays he published, he wrote: ‘I urgently call on all Jews who want to be human beings to join me in the radical condemnation of systematic torture. Where barbarism begins, even existential commitments must end.

Sea and Earth

Miri Davidson in Sidecar:

The far right wants to decolonize. In France, far-right intellectuals routinely cast Europe as indigenous victim of an ‘immigrant colonization’ orchestrated by globalist elites. Renaud Camus, theorist of the Great Replacement, has praised the anticolonial canon – ‘all the major texts in the fight against decolonization apply admirably to France, especially those of Frantz Fanon’ – and claimed that indigenous Europe needs its own FLN. A similar style of reasoning is evident among Hindu supremacists, who employ the ideas of Latin American decolonial theorists to present ethnonationalism as a form of radical indigenous critique; the lawyer and writer Sai Deepak did this so successfully that he managed to persuade decolonial theorist Walter Mignolo to write an endorsement. Meanwhile in Russia, Putin proclaims Russia’s leading role in an ‘anti-colonial movement against unipolar hegemony’, with his foreign minister Sergei Lavrov promising to stand ‘in solidarity with the African demands to complete the process of decolonization’.

The phenomenon goes beyond the kinds of reversal common to reactionary discourse. A decolonial perspective is championed by the two foremost intellectuals of the European New Right: Alain de Benoist and Alexander Dugin. In the case of de Benoist, this involved a major departure from his earlier colonialist allegiances. Coming to political consciousness during the Algerian War, he found his calling among white nationalist youth organizations seeking to prevent the collapse of the French empire. He praised the OAS for its bravery and dedicated two early two books to the implementation of white nationalism in South Africa and Rhodesia, describing South Africa under apartheid as ‘the last stronghold of the West from which we came’. Yet by the 1980s, de Benoist had shifted course. Having adopted a pagan imaginary and dropped explicit references to white nationalism, he began to orient his thought around a defence of cultural diversity.

More here.

Spinoza: Freedom’s Messiah

Joe Moshenska at The Guardian:

In December 2021, the philosopher Yitzhak Melamed posted on social media a letter that he had received from the rabbi of the Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam. Melamed had written requesting permission to film there for a documentary on the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who had been emphatically expelled by the 17th-century Jewish community. The rabbi sternly explained that the elders of that community had “excommunicated Spinoza and his writings with the severest possible ban, a ban that remains in force for all time and cannot be rescinded”. Furthermore, not only was the ban – known as a cherem – still apparently in full force, but it was contagious: because Melamed has “devoted his life to the study of Spinoza’s banned works”, he too was now declared “persona non grata in the Portuguese synagogue complex”. When Melamed was interviewed about these events on the BBC World Service, he wryly commented: “I don’t completely buy the image of this kind of zealotry, partly because the synagogue itself is selling puppets of Spinoza in their shop.” It’s true: I visited in early 2022 and bought what was then the last puppet in stock, which now sits on the mantelpiece in my office and looks down at me when I teach.

In December 2021, the philosopher Yitzhak Melamed posted on social media a letter that he had received from the rabbi of the Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam. Melamed had written requesting permission to film there for a documentary on the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who had been emphatically expelled by the 17th-century Jewish community. The rabbi sternly explained that the elders of that community had “excommunicated Spinoza and his writings with the severest possible ban, a ban that remains in force for all time and cannot be rescinded”. Furthermore, not only was the ban – known as a cherem – still apparently in full force, but it was contagious: because Melamed has “devoted his life to the study of Spinoza’s banned works”, he too was now declared “persona non grata in the Portuguese synagogue complex”. When Melamed was interviewed about these events on the BBC World Service, he wryly commented: “I don’t completely buy the image of this kind of zealotry, partly because the synagogue itself is selling puppets of Spinoza in their shop.” It’s true: I visited in early 2022 and bought what was then the last puppet in stock, which now sits on the mantelpiece in my office and looks down at me when I teach.

more here.

The Philosophy of Spinoza & Leibniz – Bryan Magee & Anthony Quinton

Delmore Schwartz’s Poems

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

Come with me, down the rabbit hole that is the life and work of the Brooklyn-born poet Delmore Schwartz (1913-66). There are two primary portals into Delmore World. Neither involves his own verse. Reading about Schwartz is more invigorating than reading him, or so I have long thought. He was so intense and unbuttoned that he inspired two of the best books of the second half of the 20th century.

Come with me, down the rabbit hole that is the life and work of the Brooklyn-born poet Delmore Schwartz (1913-66). There are two primary portals into Delmore World. Neither involves his own verse. Reading about Schwartz is more invigorating than reading him, or so I have long thought. He was so intense and unbuttoned that he inspired two of the best books of the second half of the 20th century.

The first portal is James Atlas’s 1977 biography, “Delmore Schwartz: The Life of an American Poet.” Atlas’s book has more drama and critical insight than seven or eight typical American literary biographies. I would be hard-pressed to name a better one written in the past 50 years, in terms of its style-to-substance ratio and the fat it gets into the pan.

Atlas follows Schwartz, the bumptious son of Jewish Romanian immigrants, through his alienated childhood and into his early work in the 1930s, when he was considered America’s Auden, the most promising poet of his generation.

more here.

Saturday Poem

queer ancestor(s)

at most, you are a whisper

that my mother covertly deals

over the kitchen table, eyes shifting

looking out for all vengeful ghosts

both dead and alive

she thumbs through photographs nonchalantly

her index finger stopping briefly

to shine a light, so fast, I almost missed you

but there, my pupil widens

and swallows whole

the proof of your existence

trailed by a story of maybes,

of beliefs,

of secrets,

passing by, burning bright

small shooting star

on the horizon of my life

I want to look back and wish upon you

to ask for your unabashed truth and

yank it down so that I can

thread the glow of your being through mine

by Amanda Gómez Sánchez

from Bodega Magazine

Inflamed

Jerry Groopman in The New Yorker:

Several years ago, I fell at the gym and ripped two tendons in my wrist. The pain was excruciating, and within minutes my hand had swollen grotesquely and become hot to the touch. I was reminded of a patient I’d seen early in medical school, whose bacterial infection extended from his knee to his toes. Latin was long absent from the teaching curriculum, but, as my instructor examined the leg, he cited the four classic symptoms of inflammation articulated by the Roman medical writer Celsus in the first century: rubor, redness; tumor, swelling; calor, heat; and dolor, pain. In Latin, inflammatio means “setting on fire,” and as I considered the searing pain in my injured hand I understood how the condition earned its name.

Several years ago, I fell at the gym and ripped two tendons in my wrist. The pain was excruciating, and within minutes my hand had swollen grotesquely and become hot to the touch. I was reminded of a patient I’d seen early in medical school, whose bacterial infection extended from his knee to his toes. Latin was long absent from the teaching curriculum, but, as my instructor examined the leg, he cited the four classic symptoms of inflammation articulated by the Roman medical writer Celsus in the first century: rubor, redness; tumor, swelling; calor, heat; and dolor, pain. In Latin, inflammatio means “setting on fire,” and as I considered the searing pain in my injured hand I understood how the condition earned its name.

Inflammation occurs when the body rallies to defend itself against invading microbes or to heal damaged tissue. The walls of the capillaries dilate and grow more porous, enabling white blood cells to flood the damaged site. As blood flows in and fluid leaks out, the region swells, which can put pressure on surrounding nerves, causing pain; inflammatory molecules may also activate pain fibres. The heat most likely results from the increase in blood flow.

More here.

Milk without the Cow. Eggs without the Chicken

Lindsey Doermann in Anthropocene:

In 2008, the biotech industry had fallen on tough times: capital was drying up and businesses were struggling to survive. That’s when Ryan Bethencourt saw an opportunity. A biologist with an entrepreneurial streak, he and a couple of friends started buying equipment from bankrupt companies and setting up their own small labs. By 2013, he had co-founded Counter Culture Labs, a “biohacker” space in Oakland, California. There, DIY-biology enthusiasts are now working on, among other projects, making real cheese in a way that bypasses the cow.

In 2008, the biotech industry had fallen on tough times: capital was drying up and businesses were struggling to survive. That’s when Ryan Bethencourt saw an opportunity. A biologist with an entrepreneurial streak, he and a couple of friends started buying equipment from bankrupt companies and setting up their own small labs. By 2013, he had co-founded Counter Culture Labs, a “biohacker” space in Oakland, California. There, DIY-biology enthusiasts are now working on, among other projects, making real cheese in a way that bypasses the cow.

Bethencourt is part of a growing group of scientists, entrepreneurs, and lab tinkerers who are forging a bold new food future—one without animals. But they’re not asking everyone to give up meat and dairy. Thanks to advances in synthetic biology, they’re developing ways to produce actual animal products—meat, milk, egg whites, collagen—in the lab. And in doing so, they are shrinking the carbon footprint and slashing the land and water requirements of these goods with the goal of meeting the world’s growing protein needs more sustainably.

More here.

Friday, April 12, 2024

Eliot’s Greatest Poem and His antisemitism

Nathaniel Rosenthalis in The Common Reader:

My first impression, upon opening Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem was admittedly delicious. A usual kind of epigraph greets us: “There is always another one walking beside you,” from Eliot’s poem, but then we turn the page, and on the back of the epigraph page is a quotation from Eliot, a meaty paragraph, and facing it, on the right-hand side, is a shorter passage from Pound. Right away, then, the two men are side by side, in the opening pages in a way that disrupts the usual front page material of a tome. It is a nice touch that not only forecasts the book’s focus on the relationship between the two men in the crafting of one of the inarguably influential English language poems of the twentieth century but also indicates the attention to detail and summoning of atmosphere that characterize the bulk of Hollis’s project, if not its achievement. Which is this: to demythologize, and at times painfully, re-animate the gross disturbances in Eliot’s life and character that, for better or worse, have bequeathed us the still-jarring title poem.

My first impression, upon opening Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem was admittedly delicious. A usual kind of epigraph greets us: “There is always another one walking beside you,” from Eliot’s poem, but then we turn the page, and on the back of the epigraph page is a quotation from Eliot, a meaty paragraph, and facing it, on the right-hand side, is a shorter passage from Pound. Right away, then, the two men are side by side, in the opening pages in a way that disrupts the usual front page material of a tome. It is a nice touch that not only forecasts the book’s focus on the relationship between the two men in the crafting of one of the inarguably influential English language poems of the twentieth century but also indicates the attention to detail and summoning of atmosphere that characterize the bulk of Hollis’s project, if not its achievement. Which is this: to demythologize, and at times painfully, re-animate the gross disturbances in Eliot’s life and character that, for better or worse, have bequeathed us the still-jarring title poem.

More here.

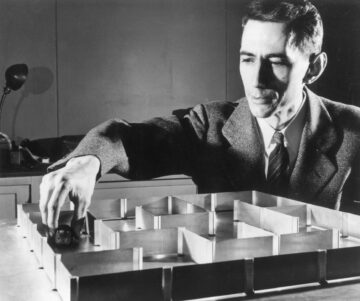

My Meeting With Claude Shannon, Father of the Information Age

John Horgan at his own website:

Claude Shannon can’t sit still. We’re in the living room of his home north of Boston, an edifice called Entropy House, and I’m trying to get him to recall how he came up with information theory. Shannon, who is a boyish 73, with a shy grin and snowy hair, is tired of dwelling on his past. He wants to show me his gadgets.

Claude Shannon can’t sit still. We’re in the living room of his home north of Boston, an edifice called Entropy House, and I’m trying to get him to recall how he came up with information theory. Shannon, who is a boyish 73, with a shy grin and snowy hair, is tired of dwelling on his past. He wants to show me his gadgets.

Over the mild protests of his wife, Betty, he leaps from his chair and disappears into another room. When I catch up with him, he proudly shows me his seven chess-playing machines, gasoline-powered pogo-stick, hundred-bladed jackknife, two-seated unicycle and countless other marvels.

Some of his personal creations–such as a mechanical mouse that navigates a maze, a juggling W. C. Fields mannequin and a computer that calculates in Roman numerals–are dusty and in disrepair. But Shannon seems as delighted with his toys as a 10-year-old on Christmas morning.

Is this the man who, at Bell Labs in 1948, wrote “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” the Magna Carta of the digital age? Whose work is described as the greatest “in the annals of technological thought” by Bell Labs executive Robert Lucky?

Yes.

More here.

Ray Kurzweil & Geoff Hinton Debate the Future of AI

Gaza and the hundred years’ war on Palestine

Rashid Khalidi in The Guardian:

For people everywhere, myself included, the awful images that have come out of Gaza and Israel since 7 October 2023 have been inescapable. This war hangs over us like a motionless black cloud that gets darker and more ominous with the passage of endless weeks of horror unspooling before our eyes. Having friends and family there makes this much harder to bear for many of us living far away.

For people everywhere, myself included, the awful images that have come out of Gaza and Israel since 7 October 2023 have been inescapable. This war hangs over us like a motionless black cloud that gets darker and more ominous with the passage of endless weeks of horror unspooling before our eyes. Having friends and family there makes this much harder to bear for many of us living far away.

Some have argued that these events represent a rupture, an upheaval, that this was “Israel’s 9/11” or that it is a new Nakba, an unprecedented genocide. Certainly, the scale of these events, the almost real-time footage of atrocities and unbearable devastation – much of it captured on phones and spread on social media – and the intensity of the global response, are unprecedented. We do seem to be in a new phase, where the execrable “Oslo process” is dead and buried, where occupation, colonisation and violence are intensifying, where international law is trampled on, and where long-fixed tectonic plates are slowly moving.

But while much has changed in the past six months, the horrors we witness can only be truly comprehended as a cataclysmic new phase in a war that has been going on for several generations.

More here.

Learning to Live Without a Self with Jay Garfield

Bees

Lauren K. Watel at Salmagundi:

I force myself to watch videos of swarms. Swarms in flight, the frantic electricity of their communal passage, as if the air were awash in buzzing embers. And swarms at rest, noisy seething clumps clinging to branches and eaves and fire hydrants and bicycles. What is it that most alarms me about these images? The ominous rumble of the swarms’ wingbeats, for one thing. The nature of their flying, its chaotic zigzaggy suddenness. And their sheer, overwhelming numbers, the teeming mass of them, angry seeming, each of them with the potential to sting, like a vast force of tiny soldiers piloting tiny fighter jets. All this footage, which I find terrifying, even menacing, has been captured and narrated and posted by enthusiastic beekeepers across the globe. Unlike me, they are far from terrified or menaced; quite the opposite, they are exhilarated, awed, grinning like children. Most extraordinarily, they talk about getting stung with the amused matter-of-factness of someone getting caught in a passing rainstorm.

I force myself to watch videos of swarms. Swarms in flight, the frantic electricity of their communal passage, as if the air were awash in buzzing embers. And swarms at rest, noisy seething clumps clinging to branches and eaves and fire hydrants and bicycles. What is it that most alarms me about these images? The ominous rumble of the swarms’ wingbeats, for one thing. The nature of their flying, its chaotic zigzaggy suddenness. And their sheer, overwhelming numbers, the teeming mass of them, angry seeming, each of them with the potential to sting, like a vast force of tiny soldiers piloting tiny fighter jets. All this footage, which I find terrifying, even menacing, has been captured and narrated and posted by enthusiastic beekeepers across the globe. Unlike me, they are far from terrified or menaced; quite the opposite, they are exhilarated, awed, grinning like children. Most extraordinarily, they talk about getting stung with the amused matter-of-factness of someone getting caught in a passing rainstorm.

more here.

Teaching In Florida

Michael Hofmann at the LRB:

We are a small part of a shrinking thing, tail to a dwindling dog, or that thing that, in Yeats, is fastened to the dying animal. The heart; the soul. The dying animal is the English department, perhaps the humanities as a whole. When I started at the University of Florida, thirty years ago, the department offered sometimes thin but fairly uninterrupted coverage from the Middle Ages to modern times. Or even Modern Times. There were sidelines in film studies, gender studies, children’s literature. Some other things. There was a faculty of eighty. Now it is a little under half that. All idea of coverage has been binned. We have someone who teaches the 18th century. An impresario who sometimes does Shakespeare. One or two that teach poetry. We have been hollowed out. We have certain specialisations, called ‘concentrations’. These enable us, without directly competing with them, to draw students away from other universities. We follow the trend. We chase the customer.

And ‘we’, the tail or the soul, not in any spiritual sense, but as an appendage – an ornament, if you want to be nice about it – ‘we’ are two fiction writers and three poets.

more here.