Jerry Groopman in The New Yorker:

Several years ago, I fell at the gym and ripped two tendons in my wrist. The pain was excruciating, and within minutes my hand had swollen grotesquely and become hot to the touch. I was reminded of a patient I’d seen early in medical school, whose bacterial infection extended from his knee to his toes. Latin was long absent from the teaching curriculum, but, as my instructor examined the leg, he cited the four classic symptoms of inflammation articulated by the Roman medical writer Celsus in the first century: rubor, redness; tumor, swelling; calor, heat; and dolor, pain. In Latin, inflammatio means “setting on fire,” and as I considered the searing pain in my injured hand I understood how the condition earned its name.

Several years ago, I fell at the gym and ripped two tendons in my wrist. The pain was excruciating, and within minutes my hand had swollen grotesquely and become hot to the touch. I was reminded of a patient I’d seen early in medical school, whose bacterial infection extended from his knee to his toes. Latin was long absent from the teaching curriculum, but, as my instructor examined the leg, he cited the four classic symptoms of inflammation articulated by the Roman medical writer Celsus in the first century: rubor, redness; tumor, swelling; calor, heat; and dolor, pain. In Latin, inflammatio means “setting on fire,” and as I considered the searing pain in my injured hand I understood how the condition earned its name.

Inflammation occurs when the body rallies to defend itself against invading microbes or to heal damaged tissue. The walls of the capillaries dilate and grow more porous, enabling white blood cells to flood the damaged site. As blood flows in and fluid leaks out, the region swells, which can put pressure on surrounding nerves, causing pain; inflammatory molecules may also activate pain fibres. The heat most likely results from the increase in blood flow.

More here.

In 2008, the biotech industry

In 2008, the biotech industry My first impression, upon opening Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem was admittedly delicious. A usual kind of epigraph greets us: “There is always another one walking beside you,” from Eliot’s poem, but then we turn the page, and on the back of the epigraph page is a quotation from Eliot, a meaty paragraph, and facing it, on the right-hand side, is a shorter passage from Pound. Right away, then, the two men are side by side, in the opening pages in a way that disrupts the usual front page material of a tome. It is a nice touch that not only forecasts the book’s focus on the relationship between the two men in the crafting of one of the inarguably influential English language poems of the twentieth century but also indicates the attention to detail and summoning of atmosphere that characterize the bulk of Hollis’s project, if not its achievement. Which is this: to demythologize, and at times painfully, re-animate the gross disturbances in Eliot’s life and character that, for better or worse, have bequeathed us the still-jarring title poem.

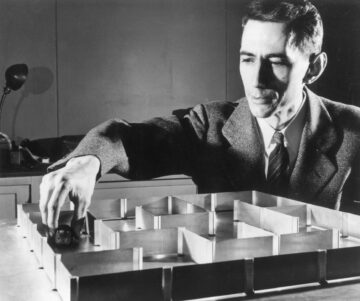

My first impression, upon opening Hollis’s The Waste Land: A Biography of a Poem was admittedly delicious. A usual kind of epigraph greets us: “There is always another one walking beside you,” from Eliot’s poem, but then we turn the page, and on the back of the epigraph page is a quotation from Eliot, a meaty paragraph, and facing it, on the right-hand side, is a shorter passage from Pound. Right away, then, the two men are side by side, in the opening pages in a way that disrupts the usual front page material of a tome. It is a nice touch that not only forecasts the book’s focus on the relationship between the two men in the crafting of one of the inarguably influential English language poems of the twentieth century but also indicates the attention to detail and summoning of atmosphere that characterize the bulk of Hollis’s project, if not its achievement. Which is this: to demythologize, and at times painfully, re-animate the gross disturbances in Eliot’s life and character that, for better or worse, have bequeathed us the still-jarring title poem. Claude Shannon can’t sit still. We’re in the living room of his home north of Boston, an edifice called Entropy House, and I’m trying to get him to recall how he came up with information theory. Shannon, who is a boyish 73, with a shy grin and snowy hair, is tired of dwelling on his past. He wants to show me his gadgets.

Claude Shannon can’t sit still. We’re in the living room of his home north of Boston, an edifice called Entropy House, and I’m trying to get him to recall how he came up with information theory. Shannon, who is a boyish 73, with a shy grin and snowy hair, is tired of dwelling on his past. He wants to show me his gadgets. F

F I force myself to watch videos of swarms. Swarms in flight, the frantic electricity of their communal passage, as if the air were awash in buzzing embers. And swarms at rest, noisy seething clumps clinging to branches and eaves and fire hydrants and bicycles. What is it that most alarms me about these images? The ominous rumble of the swarms’ wingbeats, for one thing. The nature of their flying, its chaotic zigzaggy suddenness. And their sheer, overwhelming numbers, the teeming mass of them, angry seeming, each of them with the potential to sting, like a vast force of tiny soldiers piloting tiny fighter jets. All this footage, which I find terrifying, even menacing, has been captured and narrated and posted by enthusiastic beekeepers across the globe. Unlike me, they are far from terrified or menaced; quite the opposite, they are exhilarated, awed, grinning like children. Most extraordinarily, they talk about getting stung with the amused matter-of-factness of someone getting caught in a passing rainstorm.

I force myself to watch videos of swarms. Swarms in flight, the frantic electricity of their communal passage, as if the air were awash in buzzing embers. And swarms at rest, noisy seething clumps clinging to branches and eaves and fire hydrants and bicycles. What is it that most alarms me about these images? The ominous rumble of the swarms’ wingbeats, for one thing. The nature of their flying, its chaotic zigzaggy suddenness. And their sheer, overwhelming numbers, the teeming mass of them, angry seeming, each of them with the potential to sting, like a vast force of tiny soldiers piloting tiny fighter jets. All this footage, which I find terrifying, even menacing, has been captured and narrated and posted by enthusiastic beekeepers across the globe. Unlike me, they are far from terrified or menaced; quite the opposite, they are exhilarated, awed, grinning like children. Most extraordinarily, they talk about getting stung with the amused matter-of-factness of someone getting caught in a passing rainstorm. In 1968, Tversky and Kahneman were both rising stars in the psychology department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. They had little else in common. Tversky was born in Israel and had been a military hero. He had a bit of a quiet swagger (along with, incongruously, a slight lisp). He was an optimist, not only because it suited his personality but also because, as he put it, “when you are a pessimist and the bad thing happens, you live it twice. Once when you worry about it, and the second time when it happens.” A night owl, he would often schedule meetings with his graduate students at midnight, over tea, with no one around to bother them.

In 1968, Tversky and Kahneman were both rising stars in the psychology department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. They had little else in common. Tversky was born in Israel and had been a military hero. He had a bit of a quiet swagger (along with, incongruously, a slight lisp). He was an optimist, not only because it suited his personality but also because, as he put it, “when you are a pessimist and the bad thing happens, you live it twice. Once when you worry about it, and the second time when it happens.” A night owl, he would often schedule meetings with his graduate students at midnight, over tea, with no one around to bother them. Inside the brains of people with psychosis, two key systems are malfunctioning: a “filter” that directs attention toward important external events and internal thoughts, and a “predictor” composed of pathways that anticipate rewards. Dysfunction of these systems makes it difficult to know what’s real, manifesting as hallucinations and delusions. The findings come from a Stanford Medicine-led study, published April 11 in Molecular Psychiatry, that used brain scan data from children, teens and

Inside the brains of people with psychosis, two key systems are malfunctioning: a “filter” that directs attention toward important external events and internal thoughts, and a “predictor” composed of pathways that anticipate rewards. Dysfunction of these systems makes it difficult to know what’s real, manifesting as hallucinations and delusions. The findings come from a Stanford Medicine-led study, published April 11 in Molecular Psychiatry, that used brain scan data from children, teens and  You know the stereotype of the NPR listener: an EV-driving, Wordle-playing, tote bag–carrying coastal elite. It doesn’t precisely describe me, but it’s not far off. I’m Sarah Lawrence–educated, was raised by a

You know the stereotype of the NPR listener: an EV-driving, Wordle-playing, tote bag–carrying coastal elite. It doesn’t precisely describe me, but it’s not far off. I’m Sarah Lawrence–educated, was raised by a  For more than 40 years, Avi Wigderson has studied problems. But as a computational complexity theorist, he doesn’t necessarily care about the answers to these problems. He often just wants to know if they’re solvable or not, and how to tell. “The situation is ridiculous,” said

For more than 40 years, Avi Wigderson has studied problems. But as a computational complexity theorist, he doesn’t necessarily care about the answers to these problems. He often just wants to know if they’re solvable or not, and how to tell. “The situation is ridiculous,” said

From St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, a lane once led through fields up to a small patch of grass. In the centre of this green, where formerly stood a stake, there is now a stone slab engraved: ‘in memory of those accused of witchcraft’. Convicted at trials held in the cathedral, the condemned were marched up the lane with hands bound, lashed to the stake and then ‘wyrried’ – that is strangled to death by the public executioner – and burned to ash. Other forms of execution were available; common criminals and traitors might also be wyrried but not reduced to ashes. Burning, however, was ‘cheust’ – ‘just’ – for witches. Yet the witches were otherwise quite undistinguished: ‘they wur cheust folk’ declares the slab’s main inscription in suitably Orcadian spelling.

From St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, a lane once led through fields up to a small patch of grass. In the centre of this green, where formerly stood a stake, there is now a stone slab engraved: ‘in memory of those accused of witchcraft’. Convicted at trials held in the cathedral, the condemned were marched up the lane with hands bound, lashed to the stake and then ‘wyrried’ – that is strangled to death by the public executioner – and burned to ash. Other forms of execution were available; common criminals and traitors might also be wyrried but not reduced to ashes. Burning, however, was ‘cheust’ – ‘just’ – for witches. Yet the witches were otherwise quite undistinguished: ‘they wur cheust folk’ declares the slab’s main inscription in suitably Orcadian spelling.